Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 19, No. 1 (2022)

Myth Busting the Writing Center: A Critical Inquiry of Ideologies and Practices

Bethany Meadows

Michigan State University

meadow53@msu.edu

Trixie G. Smith

Michigan State University

smit1254@msu.edu

We were asked to talk about the state of the field at this moment in time, this mid-pandemic moment that has urged all of us to rethink much of the work we do in our writing centers, or at least how we do the work. This moment is also full of racial violence and proud proclamations of racism from police brutality to targeted shootings to riots at the U.S. Capitol. This moment of continued sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, classism and more. All of these moments affect us as human beings working in the center with and alongside other human beings, consulting sessions with both consultants and writers who have a range of embodied experiences, traumas, and understandings that they bring to their writing and to their sessions.

In our writing center at Michigan State University, engaging with these moments and all that they indicate about the state of the world around us has necessitated being very deliberate about our philosophies and positions; it has also meant making sure that our practices, policies, and procedures all align with our stated beliefs. The big picture, if you will. It should come as no surprise then, that this engagement with both theory and practice, has resulted in many questions, tensions, and downright resistance with many of the accepted stances in the field, the canon of writing centers as others have called it. This questioning, however, has also revealed that despite the canon, perhaps even through it at times, that resistance and calls for more inclusive and just writing centers have always existed. Even as folks were defining the field in the 1980s, others were pushing against it, asking writing center professionals and practitioners to do more, to question more, to call out the academy when it wasn’t/isn’t serving students humanely and fairly.

Considering the state of the field, led Bethany to think about a video game she plays. In Democracy 3 (Positech Games), you play as an elected official and try to get policies passed to be re-elected. In the game, events and policies exist in different thematic realms (e.g., criminal justice, social welfare, taxes, healthcare, education, etc.). If you hover your computer cursor over a single policy or event, you see how it is being affected (both negatively and/or positively) by other policies and events as well as its effect on others. From this, you cannot separate them into mutually exclusive bubbles, but instead they all overlap and affect one another. This relates to the state of writing centers—every happening, every promising practice, every practice based in myths or misguided beliefs all relate and affect each other. We cannot focus on one area at a time. We must look at how they are conversing with and impacting others.

For instance, at an East Central Writing Center Association (ECWCA) book chat, we discussed Wooten et al.’s edited collection, The Things We Carry. During Bethany’s second book chat session, she was placed in a Zoom breakout room with two writing center directors. They were each asked to describe their writing center spaces and relate them to the book. In this discussion, one director described their center as a “very cozy place where people feel at home,” and the other director responded in agreement before discussing their center as a “safe space.” But, as other scholars have discussed, many times this is not the case in our centers. For Bethany, it has most definitely been the case in several centers where she has experienced biphobia, sexism, ableism as well as heard other oppressive ideologies uttered by both clients and writing center professionals. After Bethany relayed this story to Trixie, Trixie discussed those misguided ideologies as part of the reason she preferred to think of the MSU Writing Center as a brave space, as well as a space that is always evolving.

From the genesis of this conversation, Trixie and Bethany began to brainstorm a list of myths that we still hear perpetuated in our everyday discourse of writing centers, at conferences, on listservs, in training guides, and even in our journals. Many of these myths have already been called out or disrupted within writing center scholarship (Grimm; Grutsch McKinney; Greenfield), but as evident by the informal book chat, these universalizing tropes, as well as many other myths still pervade our everyday work and interactions with writers and each other as writing center professionals.

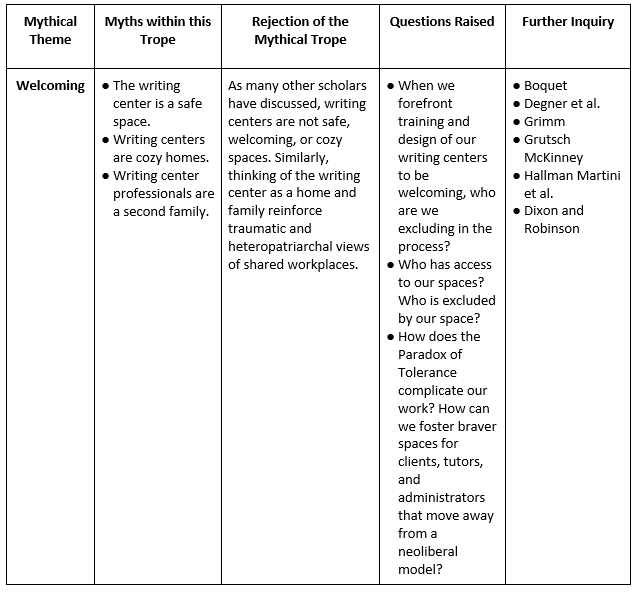

In this short essay, we will describe some of the myths still being perpetuated in informal and formal discourse and practices and then conclude with a call to action. In the following chart, we offer a common mythical theme in writing center work, a rejection of that myth, questions raised by this tension, and a sampling of where you can go for further information and inquiry.

While there are no “best practices” in our work, there can be practices that are less harmful than others. To conclude, we urge writing center professionals to continually interrogate their beliefs and practices in order to evolve. In fact, we challenge you to expand this list by examining the practices and guiding beliefs in your own centers. Do your stated beliefs, philosophies, visions, missions actually coincide with your practices, policies, and procedures? Can you explain to others the theoretical and pedagogical underpinnings of both? Do you have a plan for conveying this foundation to your staff and stakeholders?

The work we as writing center professionals have already done is important and was good for the time, but we cannot stagnant in that progress. Ongoing research, new critiques, repeated inquiries, mean new opportunities to question how and what we do, make critical pedagogical choices, and move away from a mythical, neoliberal canon. The only norm we should have is a constant, critical engagement and questioning of our praxis and theory.

Works Cited

Appleton Pine, Andrew, and Karen Moroski-Rigney. “‘What About Access?’ Writing an Accessibility Statement for Your Writing Center.” The Peer Review, vol. 4, no. 2, Oct. 2020, thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-4-2/what-about-access-writing-an-accessibility-statement-for-your-writing-center/.

Boquet, Elizabeth. Noise from the Writing Center. Utah State University Press, 2002.

Carino, Peter. “Power and Authority in Peer Tutoring.” Center Will Hold, edited by Michael A. Pemberton and Joyce Kinkead, University Press of Colorado, 2003, pp. 96–113, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt46nxnq.9.

Cedillo, Christina. “What Does It Mean to Move?: Race, Disability, and Critical Embodiment Pedagogy.” Composition Forum, vol. 39, Summer 2018, compositionforum.com/issue/39/to-move.php.

Degner, Hillary, et al. “Opening Closed Doors: A Rationale for Creating a Safe Space for Tutors Struggling with Mental Health Concerns or Illnesses.” Praxis, vol. 13, no. 1, 2015, www.praxisuwc.com/degner-et-al-131.

Denny, Harry C., et al. Out in the Center: Public Controversies and Private Struggles. Utah State University Press, 2018.

Denton, Kathryn. “Beyond the Lore: A Case for Asynchronous Online Tutoring Research.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 36, no. 2, Writing Center Journal, 2017, pp. 175–203.

Dixon, Elise. “Strategy-Centered or Student-Centered?: A Meditationon Conflation.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 42, no. 3–4, Dec. 2017, pp. 7–14.

Dixon, Elise, and Rachel Robinson, editors. “Special Issue: (Re)Defining Welcome.” The Peer Review, vol. 3, no. 1, Summer 2019, thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/?

East Central Writing Center Association. ECWCA Discussion of Section 2: Preserving Communities.

Geller, Anne Ellen, et al., editors. The Everyday Writing Center: A Community of Practice. Utah State University Press, 2007.

Green, Neisha-Anne. “Moving beyond Alright: And the Emotional Toll of This, My Life Matters Too, in the Writing Center Work.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 37, no. 1, Writing Center Journal, 2018, pp. 15–34.

Greenfield, Laura. Radical Writing Center Praxis: A Paradigm for Ethical Political Engagement. Utah State University Press, 2019.

Greenfield, Laura, and Karen Rowan, editors. Writing Centers and the New Racism: A Call for Sustainable Dialogue and Change. Utah State University Press, 2011.

Grimm, Nancy Maloney. Good Intentions: Writing Center Work for Postmodern Times. Boynton/Cook-Heinemann, 1999.

Grutsch McKinney, Jackie. Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers. University Press of Colorado, 2013. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgk97.

Hallman Martini, Rebecca, et al., editors. “Writing Centers as Brave/r Spaces.” The Peer Review, vol. 1, no. 2, Fall 2017, thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/.

Harris, Emma, and Emily Kayden. “Pandemic Consultations Create Space for Accessible Practices through Technological Affordances and Reflection.” Dangling Modifier, Spring 2021, sites.psu.edu/thedanglingmodifier/?p=4353&preview_id=4353.

Mingus, Mia. “Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice.” Leaving Evidence, 12 Apr. 2017, leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/access-intimacy-interdependence-and-disability-justice/.

Positech Games. Democracy 3. 2013.

Rafoth, Ben. “Faces, Factories, and Warhols: A r(Evoluntionary) Future for Writing Centers.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 2, Writing Center Journal, 2016, pp. 17–30.

Riddick, Sarah, and Tristin Hooker, editors. “Race & the Writing Center.” The Peer Review, vol. 16, no. 2, Summer 2019, www.praxisuwc.com/162-links-page.

Webster, Travis. Queerly Centered: LGBTQA Writing Center Directors Navigate the Workplace. Utah State University Press, 2021.

Wooten, Courtney Adams, et al., editors. The Things We Carry: Strategies for Recognizing and Negotiating Emotional Labor in Writing Program Administration. Utah State University Press, 2020.

Appendix A

Table 1: Common Writing Center Myths

Table 1: Common Writing Center Myths (Continued)

Table 1: Common Writing Center Myths (Continued)