Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 20, No. 2 (2023)

What’s Your Plan for the Consultation? Examining Alignment between Tutorial Plans and Consultations among Writing Tutors Using the Read/Plan-Ahead Tutoring Method

Diana Awad Scrocco

Youngstown State University

dlawadscrocco@ysu.edu

Abstract

Writing center scholars and tutor-training manuals historically emphasize the importance of tutors and writers collaboratively negotiating consultation agendas to maintain writers’ ownership over their writing. However, when tutors encounter advanced student writers, writers from unfamiliar fields, or writers with complex linguistic repertoires, they may struggle to read student writing, identify writing issues, and negotiate effective, mutual agendas. One tool for navigating these challenges is the “read-ahead method”—in which tutors read student writing in advance and prepare for consultations (Scrocco 10). While this method offers potential advantages, a brief survey reveals that some writing center administrators worry that tutors who read student writing in advance may hijack consultation agendas. This exploratory mixed-methods study examines thirteen tutor-supervisor planning conversations and subsequent consultations to assess the correspondence between tutors’ plans and consultations and to consider what factors may support or undermine writers’ agendas. Results suggest that tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method do not fervently push their planned agendas over writers’ agendas. However, very detailed or particularly vague pre-consultation planning may set tutors up for sessions that fail to negotiate and carry out cohesive, well-prioritized shared agendas. The most collaborative, coherent consultations in this study balance tutor and writer agendas. They begin with writers’ submitted concerns, identify high-priority global writing issues, engage in substantive agenda-setting with writers, explicitly link tutors’ plans with writers’ agendas, and abandon tutors’ plans when needed. The read/plan-ahead model works best when tutors remember to place writers at the heart of building, revising, and enacting consultation agendas.

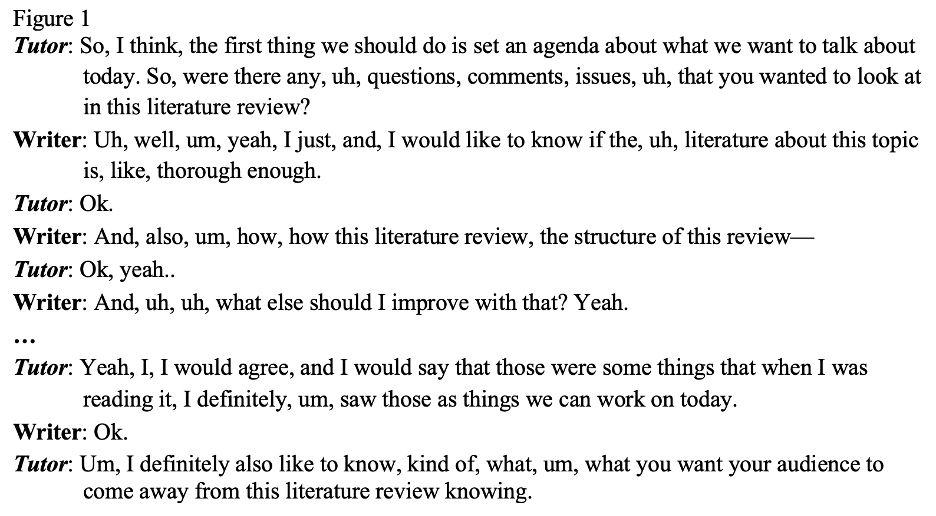

In the writing consultation excerpt in figure 1 between a graduate student tutor and multilingual international graduate student1, the tutor opens with a common writing-center move: he invites the writer to negotiate the session agenda. Unlike tutors in many centers, though, this tutor works in a center that uses the “read-ahead method” (Scrocco 14), in which writers submit written work prior to their appointments so tutors can read and plan an instructional approach. While reviewing writers’ drafts in advance may afford tutors and writers advantages, one key risk emerges: tutors who plan for consultations may assume a more dominant role in a context where writers expect authorial control. In this study, I ask: when using the read/plan-ahead method, how can tutors maximize the method’s instructional benefits and simultaneously involve writers in agenda setting?

To explore affordances and constraints of this model, I analyze thirteen tutor-supervisor planning conversations and tutors’ subsequent consultations. My analysis considers writing center administrators’ common concerns about the read/plan-ahead model, offers guidance for using this model prudently, and proposes avenues for future research. A brief survey of writing center administrators suggests that the read/plan-ahead model remains fairly uncommon—in part because many administrators worry that tutors who use this tool might be more likely to control the consultation with their planned agendas instead of collaboratively building agendas with writers. My results suggest that while tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method do introduce their instructional plans during consultations, most of the tutors in this study also elicit and address writers’ agenda items; this finding should reassure writing center administrators that tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method typically still seek and cover writers’ concerns during consultations. My qualitative analysis points to some strategies administrators and tutors can employ when using the read/plan-ahead method in order to minimize the likelihood of tutors sidelining writers’ agendas. These approaches include preparing a limited list of higher-order concerns to consider during consultations and formulating a list of questions to ask writers to encourage their active involvement in consultations.

Literature review

Historically, writing center scholarship has touted the importance of collaborative consultation agenda setting, in part because writers feel more satisfied with consultations that focus on their preferred agendas (Black 155; Mackiewicz and Thompson 60; Thompson et al. 82; Walker 72). Jointly constructed agendas afford writers ownership over their writing process and improve the likelihood that they will utilize tutor/teacher feedback during revision (Mackiewicz and Thompson 64; Thompson 417; Williams 185). Moreover, collaborative agenda setting enriches tutor-writer relationships (Black 21; Corbett 84) and keeps consultations on track (Newkirk 313; Severino 109). Shared agenda setting ideally ensures that consultations consider key global writing issues and that writing tutors do not dominate consultations (Mackiewicz and Thompson 15; Nickel 145; Severino 109; Valentine 93).

Achieving a mutually accepted writing consultation agenda is sometimes presented as an uncomplicated collaborative endeavor (Harris 374; Macauley 3). Tutors have traditionally been discouraged from bringing concrete plans to their conferences (Harris 33-34) and encouraged to ask writers to identify their concerns (Caposella 11; Kent 152; (Newkirk 303; Thonus 111). Non-directive, “student-centered” approaches (Reigstad and McAndrew 36) avoid “impos[ing] our agenda onto a writer and their text” (Anglesey and McBride). Tutor-training manuals outline how tutors and writers can negotiate “mutually agreeable goal[s]” (Gillespie and Lerner 39) for consultations: ask writers open-ended questions (Gillespie and Lerner 28-29; Ryan and Zimmerelli 16); build agendas around high-priority writing issues (Caposella 12-13; Ryan and Zimmerelli 14); and do not “presume… [to] understand better than the writer[s] what the session needs to be about” (Macauley 6). Warnings about tutors exercising undue control over session agendas have appeared in tutor-training guides for decades (Gillespie and Lerner 41-42).

Contrary to this advice, though, research suggests that some writers need more direction during agenda setting (Thompson 418-419). Moreover, tutors and writers sometimes disagree on the appropriate degree of directiveness during sessions (Clark 44; Thonus 124). Cultural norms and perceptions of teacher/tutor-student relationships inhibit some writers’ active participation in agenda setting (Ewert 2544; Lee 431; Weigle and Nelson 219). During agenda setting, some writers may interpret non-directive approaches as frustrating or directive approaches as disrespectful to their autonomy; either scenario can create negative perceptions that may influence writers’ satisfaction with consultations and their likelihood of using tutor feedback.

Undoubtedly, some writing center contexts create real challenges for negotiating well-prioritized, shared agendas. When students bring advanced writing from fields and genres unfamiliar to tutors, tutors may struggle to read student writing, identify key writing issues, and set shared agendas with writers (Scrocco 13). In such consultations, tutors may have trouble reading and evaluating writers’ texts during consultations and identifying high-priority writing issues (Scrocco 11). For example, Jo Mackiewicz’s research reveals that tutors who lacked content-area knowledge in engineering assumed too much control over consultation agendas (“The Effects” 317), focused on lower-order concerns, and provided incorrect advice (319-320). Such tendencies contradict fundamental writing-center principles of placing writers’ concerns at the center of sessions and prioritizing global writing issues.

One emerging tool for navigating these challenges is the read/plan-ahead method: tutors read students’ writing in advance and develop well-prioritized, research-driven instructional plans (Scrocco 10). In centers where writers come from advanced, highly technical fields, bring genres unfamiliar to tutors, or possess diverse linguistic repertoires, the read/plan-ahead method may represent a game-changing strategy for improving tutor feedback (Scrocco 17). Furthermore, tutors with specific identity traits and conditions, such as anxiety, learning differences, or neurological disorders (e.g., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder), may benefit from the opportunity to prepare for consultations with writers who bring challenging texts and writing needs. Despite the potential benefits of the read/plan-ahead method, this practice may encourage tutors to promote their own agendas more ardently than they might if they had arrived at consultations without premeditated plans. And if writers “sense an undeclared agenda, they can feel manipulated” (Cogie 40), potentially leading them to feel disengaged or resistant to tutors’ advice.

Survey on perceptions of read/plan-ahead method

To assess the current prevalence of the read/plan-ahead tutoring method and administrators’ apprehensions about this practice, I emailed a short IRB-approved survey to the Wcenter listserv and contacts at the seventy writing centers in my original review of websites (Scrocco 11). My survey asked respondents the following:

whether their centers use the read/plan-ahead method and under what circumstances

whether respondents have concerns about the practice.

Findings of this brief survey show that among eighteen responses, 11.11% allow the read-ahead method for any writer, 27.78% allow the practice only under specific circumstances, and 61.11% do not allow the practice at all. Among centers that allow the practice for certain consultations, only graduate-level or post-doctoral writers, faculty, and students working on lengthy projects may submit work in advance.

This short survey suggests that the read/plan-ahead method remains limited by logistical constraints (e.g., extra time and pay for tutors) and pedagogical concerns. Some respondents fear that tutors who read student writing in advance may hijack consultation agendas. Others worry that the read/plan-ahead model positions tutors as expert instructors rather than peer collaborators. Still others believe this method inhibits tutor-writer dialogue, encourages tutors to be overly directive, places undue focus on editing, and limits the traditional practice of reading writers’ work aloud. Conversely, survey respondents who use the read/plan-ahead method praise the practice for relieving tutor anxiety—particularly in sessions with advanced writers—and for helping tutors offer better feedback. My survey reveals some perceived concerns and benefits of the read/plan-ahead method and highlights the importance of collecting concrete data on the practice to identify evidence-based affordances and constraints.

Current Study

To interrogate common views of the read/plan-ahead method, this study examines the dynamics of tutor-supervisor planning conversations and subsequent tutor-writer consultations. I consider which factors in read/plan-ahead consultations appear to support or detract from writers’ agendas. This study examines thirteen tutors’ pre-consultation planning meetings and subsequent consultations in a writing center that exclusively uses the read/plan-ahead method. I seek to answer these research questions:

During read/plan-ahead consultations, to what extent do the agenda items tutors and supervisors plan align with agendas that are proposed and covered during consultations?

What potential benefits and constraints emerge in read/plan-ahead consultations as tutors and writers negotiate and enact tutorial agendas?

In this exploratory, mixed-method study, I use quantitative tools to trace the correspondence between tutors’ pre-consultation plans, proposed agendas discussed with writers, and covered agendas addressed during consultations. To add context to these results, I qualitatively analyze tutor-writer exemplars from my data set to examine advantages and limitations of this tutoring method. Armed with evidence from read/plan-ahead consultations, writing center professionals can consider and modify this practice to meet the needs of their center’s tutors and writers.

methodology

Context of the Writing Center Under Consideration

This study occurred at a private, doctoral-granting institution in 2017 when 56% of writers at this writing center were graduate-level or postgraduate writers. Writers were predominantly non-humanities, multilingual international students. Most tutors were graduate students, and all tutors completed a semester-long tutor-training course taught by rhetoric and composition faculty. The tutor-training course covered writing-pedagogy scholarship and instructional methods aimed to assist research writers across disciplines—e.g., common “novelty” moves in research-based introductions, genre moves in “IMRaD” papers, and the notion of “bottom line up front.” During the first few semesters of tutoring, tutors regularly participated in pre-consultation planning meetings with their supervisors; thereafter, tutors read and planned for consultations independently, only seeking supervisors’ advice when needed.

Context of Data Collection

Data collection occurred on three days—one day at the end of spring semester and two days about one month apart during the subsequent fall semester. All scheduled tutors were invited to participate. Thirteen tutor-writer cases were included in this study. All tutors read student writing in advance and consulted with supervisors and the researcher, who previously co-directed the center for one year five years earlier.2 The university’s institutional review board approved the research, and all participants provided consent for their planning conversations, consultations, and electronic appointment data to be recorded. Recordings were transcribed using Deborah Tannen’s method.3

Analytical Procedure

Analysis involved 1) labeling and categorizing writing issues identified in tutors’ pre-consultation planning conversations (planned agenda items); 2) labeling agenda-setting phases and writing issues proposed and covered during tutor-writer consultations; and 3) tracing the alignment of writing items across planned, proposed, and covered domains.

1. Labeling Writing Items in Tutors’ Planning Conversations

I analyzed tutor-supervisor planning conversation transcripts using Mackiewicz and Thompson’s notions of pedagogical topics and actions (28). I coded agenda-focused independent clauses as planned topics (writing issues or concepts) or actions (concrete pedagogical exercises, resources, or actions that apply writing topics). I then synthesized related topics and actions into broad categories of “writing items.” I created a master list of writing items (see Appendix A), which encompasses general writing issues and competencies (e.g., thesis, grammar, content development) and common sections of genres (e.g., discussion section, executive summary, literature review).

1. Labeling Agenda-Setting Phases and Agenda Items during Writing Consultations

Next, I analyzed writer-tutor consultation transcripts. I identified agenda-setting exchanges in which tutors and writers propose writing topics or actions to address during consultations. Using Reinking’s “agenda-setting components” (ix), Mackiewicz and Thompson’s “opening stage” (4) and “closing stage” (78), and Thonus’s “diagnosis period of a tutorial” (256), I defined agenda-setting phases as marked conversational exchange(s) in which tutors or writers propose to address writing questions, topics, or issues. I included direct agenda-setting turns (e.g., “What are your concerns?”) and indirect turns (“Do you have any other questions?”) throughout sessions.

I then labeled “proposed agenda items” and “covered agenda items” in consultations. Proposed topics and actions include the writing issues either interlocutor proposes and/or explicitly plans to discuss during consultations. Covered topics and actions include writing items writers and tutors give sustained attention during “teaching stage[s]” of consultations (Mackiewicz and Thompson 173), regardless of whether they explicitly proposed the topic or action during agenda setting. I define “sustained attention” as exchanges involving more than a few cursory conversational turns related to a writing item.

2. Tracing Alignment Across Planned, Proposed, and Covered Domains

For my quantitative analysis, I consolidated lists of agenda topics and actions into “planned agenda items,” “proposed agenda items,” and “covered agenda items” and traced the extent to which tutors’ plans emerge during subsequent consultations. To ensure analytical accuracy, I independently coded my transcripts three separate times to generate lists of planned, proposed, and covered writing items for all tutor-writer cases. Then, I collaborated with an outside rater to refine my analysis.4 The outside rater and I first met to review and refine my master list of writing items and definitions. Next, we independently used the master list of writing items/definitions to analyze all transcripts and generate lists of planned, proposed, and covered writing items for each tutor-writer case. We met to compare our lists, negotiate discrepancies, and achieve consensus in the final lists.

Once we established final lists of writing items for all cases, I created agenda-alignment tables that mapped the writing items across planned, proposed, and covered domains. I examined individual rows within tutors’ agenda-alignment tables and tallied correspondence between writing items. I counted the presence or absence of the same writing item across three domains of planning, proposing, and covering, and I generated the following agenda-alignment percentages:

planned/proposed percentage: total number of agenda items tutors plan with supervisors divided by total number of agenda items tutors and writers propose to cover during agenda setting

planned/covered percentage: total number of planned agenda items divided by total number of items covered during teaching/instructional stages of subsequent consultations

proposed/covered percentage: total number of planned items divided by total number of covered items

planned/proposed/covered percentage: total number of writing items appearing in all three domains divided by the total number of writing items for the entire tutor-writer case

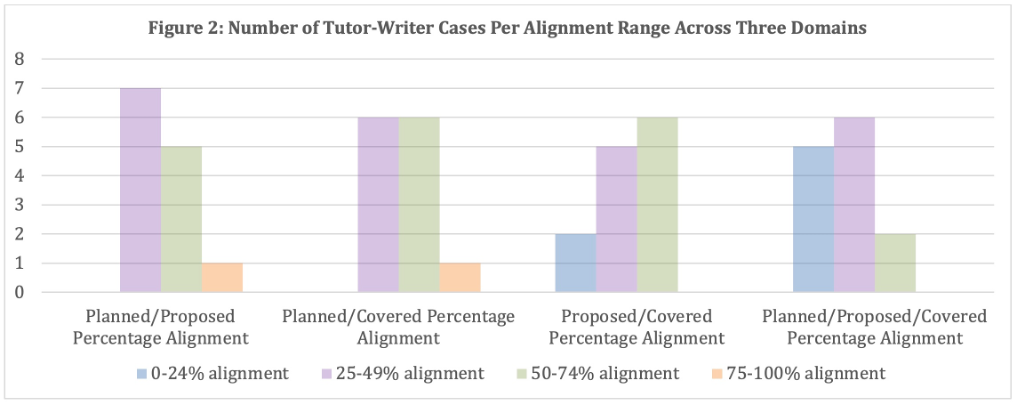

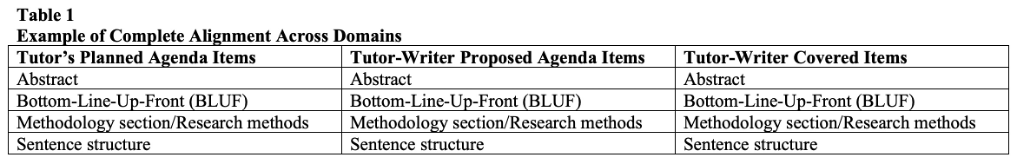

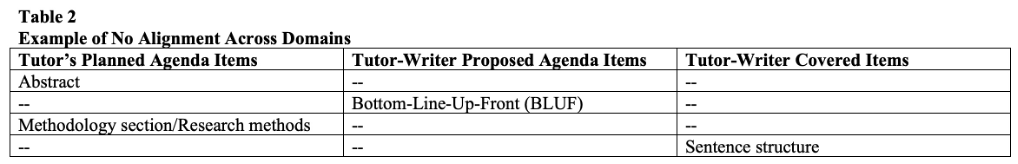

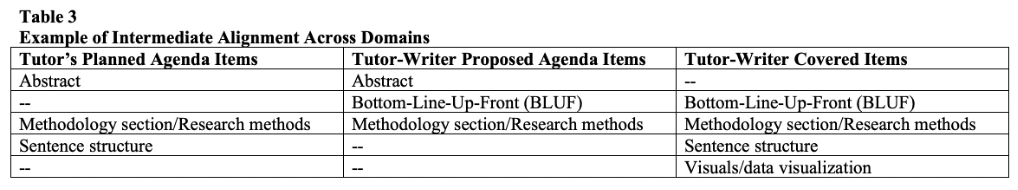

To synthesize these alignment percentages, I counted the number of tutor-writer cases that fell into the 0-24% range, 25-49% range, 50-74% range, and 75-100% range for each combination. See table 1 for an example of full alignment across domains and table 2 for an example of no alignment across domains. Table 3 is an example of a consultation in which the tutor and writer propose and cover some of the tutor’s planned items; fail to propose and cover some planned items; and add some additional writing items not planned or proposed.

4. Qualitative Analysis

To avoid relying on reductive quantitative findings, I wrote qualitative descriptions of each tutor-writer case. These descriptions note the nature of the tutor-supervisor planning conversations, the global and local writing concerns addressed, and the dynamics of tutor-supervisor and tutor-writer interactions. I used the contexts of preparation chats and consultations to theorize explanations for the alignment across domains.

Quantitative Results

This section summarizes individual tutor-writer alignment statistics and alignment percentages of all tutor-writer cases.

Individual Tutor-Writer Case Results

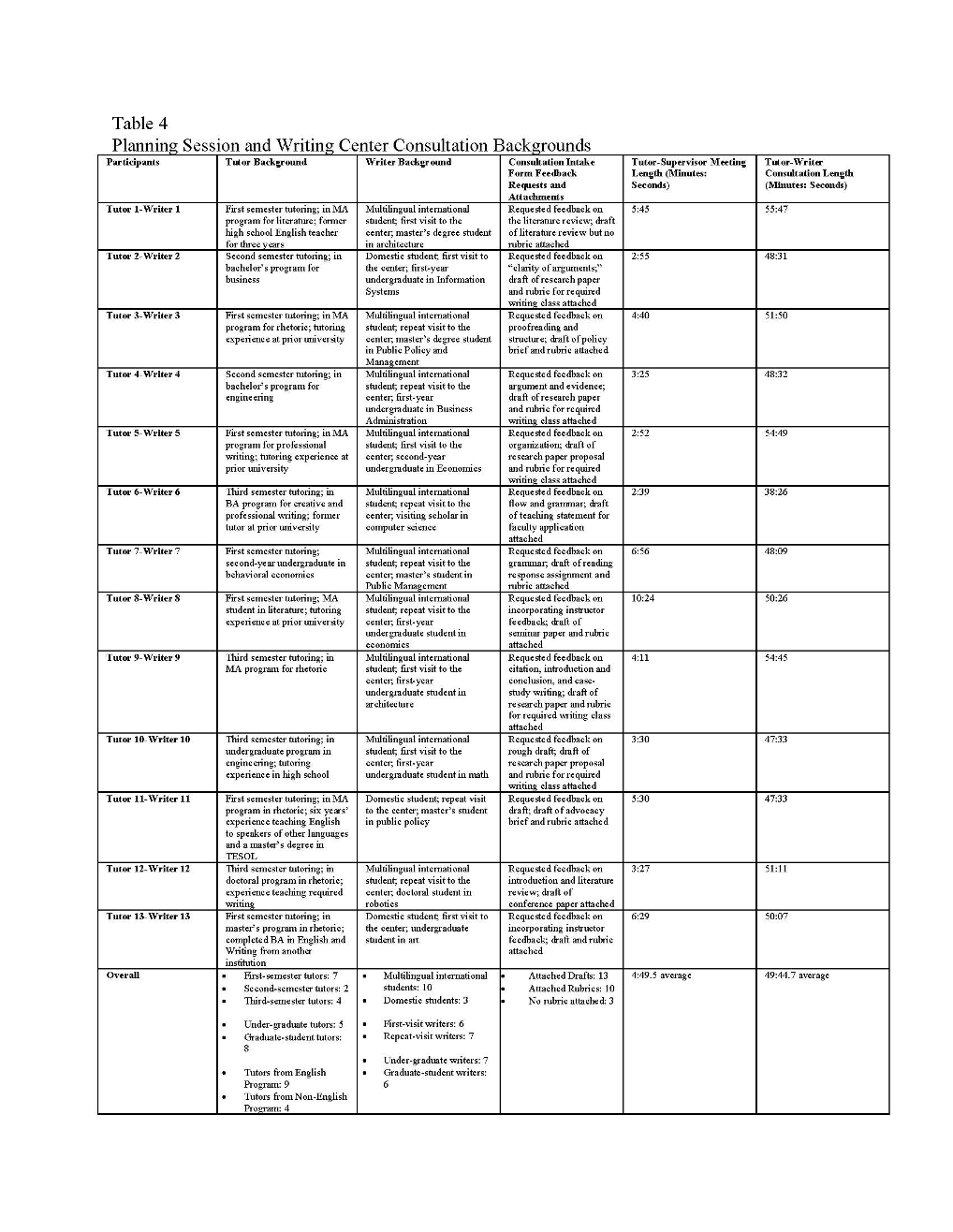

Table 4 outlines the backgrounds of tutors and writers, requested feedback from writers’ intake forms, attached documents reviewed during session planning, and time spent on individual tutor-supervisor meetings and tutor-writer consultations. About half of the tutors in this study are first-semester tutors (7), and about half are second- (2) and third-semester (4) tutors. More tutors are graduate students (8) than undergraduates (5), and most come from English-related programs (9) rather than non-English programs (4). Most writers in these consultations are multilingual international students (10) rather than domestic students5 (3). About half of these consultations are first visits to the center (6), and about half are repeat visits (7). About half of the writers are undergraduates (7), and approximately half are graduate-student writers (6). All 13 writers attached written drafts, and 10 writers attached assignment rubrics to their intake forms for tutors to review. Tutors’ preparation/planning conversations with supervisors run an average of 4 minutes and 49.5 seconds, and tutor-writer consultations run an average of 49 minutes and 44.7 seconds.

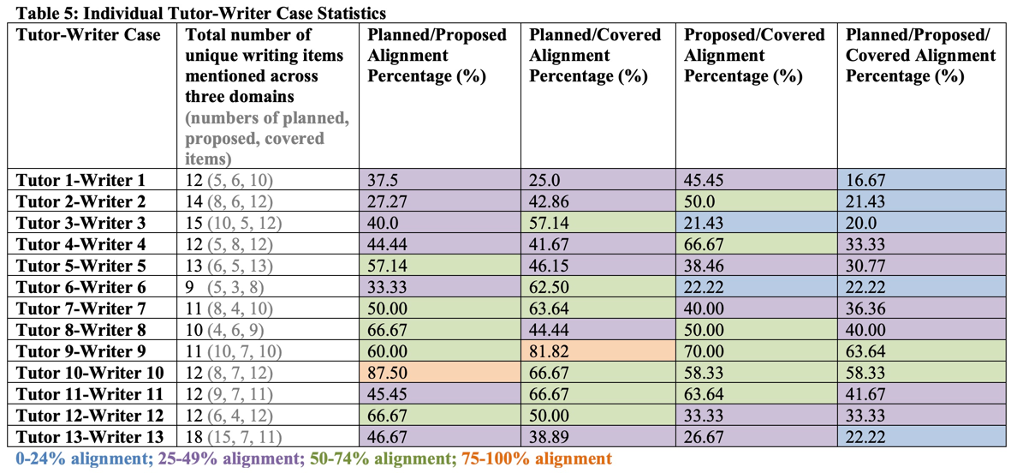

Table 5 shows statistics for individual tutor-writer cases:

number of writing items mentioned across planned, proposed, and covered domains;

in parentheses, numbers of writing items for each tutor-writer case’s planned, proposed, and covered lists;

alignment percentages across four combinations of domains:

planned/proposed alignment

planned/covered alignment

proposed/covered alignment

planned/proposed/covered alignment

Most tutors’ alignment percentages fall into the ranges of 25-49% or 50-74% alignment. For planned/proposed alignment, planned/covered alignment, and proposed/covered alignment, 2 tutor-writer cases fall below 25% alignment, and 2 tutor-writer cases exceed 74% alignment in any column. For alignment of writing items across all three domains, 5 tutor-writer cases fall below 25% alignment; 6 tutor-writer cases fall into the 25-49% alignment range; and 2 tutor-writer cases fall into the 50-74% alignment range.

Combined Alignment Statistics

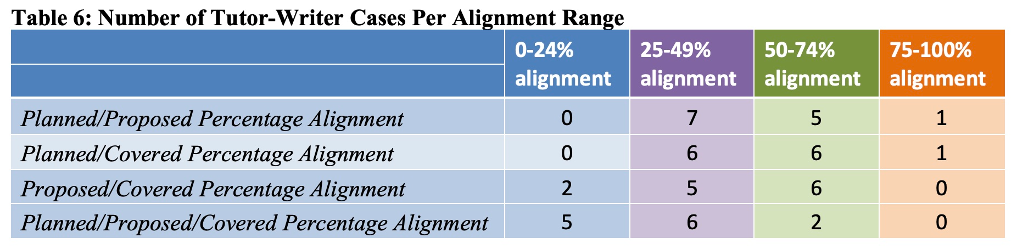

As table 6 and figure 2 illustrate, most tutor-writer cases fall into the 25-74% alignment ranges for all combinations of domains. For alignment between planned/proposed writing items, 7 tutor-writer cases fall into the 25-49% alignment range, 5 cases fall into the 50-74% range, and 1 case falls into the 74-100% range. For alignment between planned/covered writing items, 6 tutor-writer cases fall into the 25-49% alignment range, and 6 cases fall into the 50-74% range. For alignment between proposed/covered writing items, 2 tutor-writer cases fall into the 0-24% alignment range, 5 cases fall into the 25-49% range, and 6 cases fall into the 50-74% range. For alignment across all three domains (planned, proposed, and covered), most tutor-writer cases fall into the 0-49% alignment range: 5 cases fall into the 0-24% range, 6 cases fall into the 25-49%, and 2 cases fall into the 50-74% range.

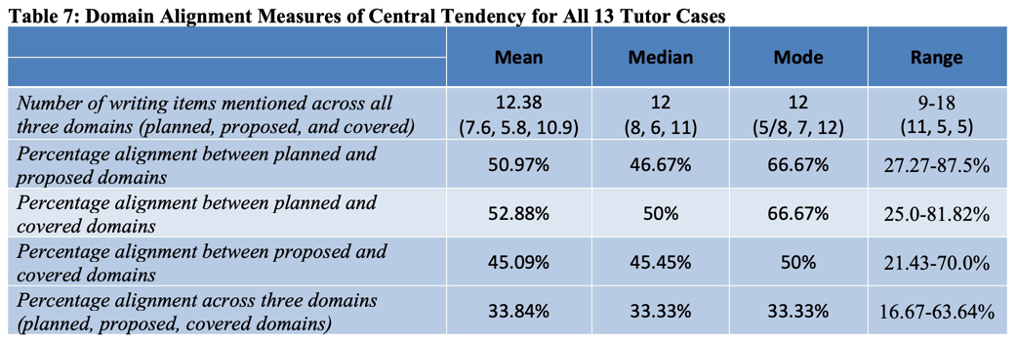

Table 7 displays measures of central tendency across all 13 tutor-writer cases, demonstrating the mean, median, mode, and range of the following: total number of writing items mentioned across the three domains, and alignment percentages between planned and proposed writing items, planned and covered writing items, proposed and covered writing items, and across all three domains. An average of 12 writing items emerges per tutor-writer case across planning conversations and consultations. Tutors plan an average of 7.6 writing items, propose 5.8 items, and cover 10.9 items. An average of 50.97% of writing items tutors plan ultimately emerges as proposed agenda items during consultations. An average of 52.88% of writing items tutors plan with supervisors receives coverage during consultations. An average of 45.09% of writing items tutors and writers propose during agenda-setting phases of consultations receives coverage during teaching phases of consultations. As for alignment percentages across all three domains, approximately one-third (33.84%) of writing items tutors plan to address emerges in both proposed and covered domains during consultations.

Qualitative Results

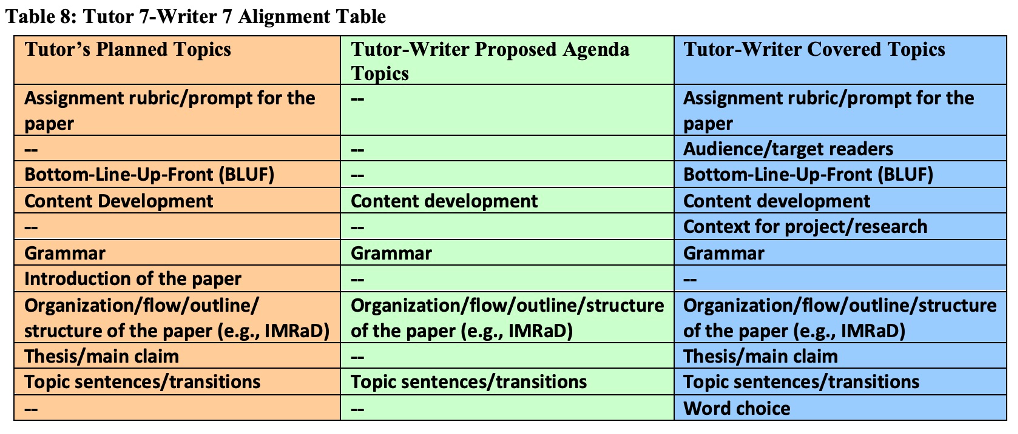

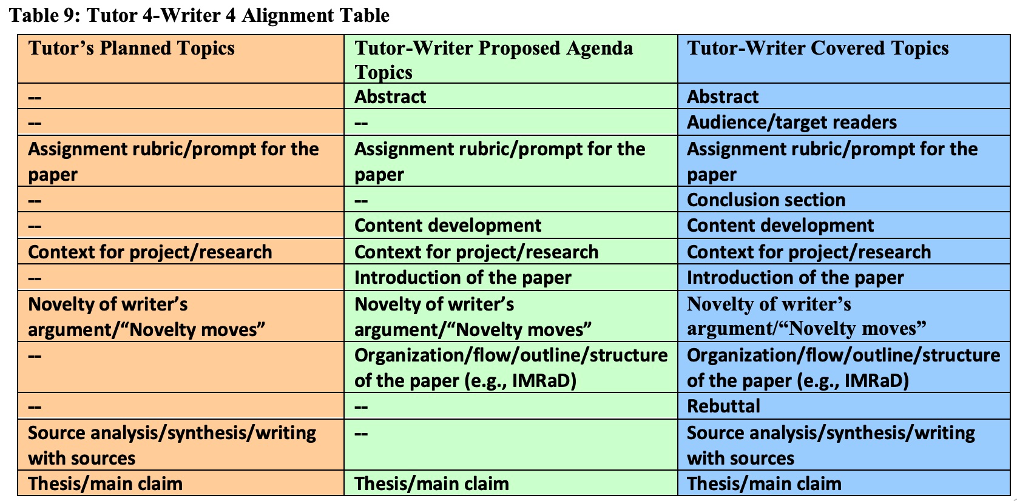

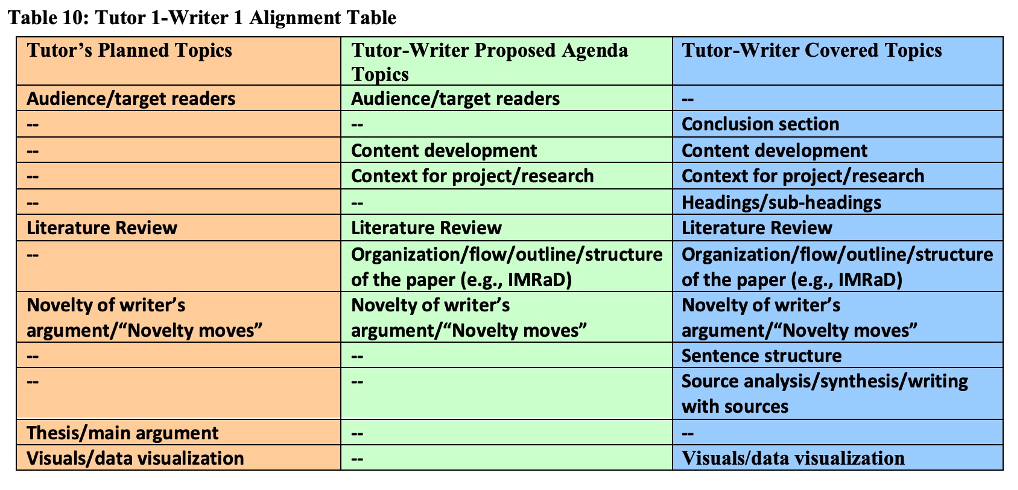

This section adds texture to my quantitative results by qualitatively analyzing three tutor-writer cases. These cases reflect quantitative results slightly above or below this study’s averages (see tables 5 and 7). I aim to analyze some scenarios that unfold when tutors use the read/plan-ahead method, and I highlight both missteps and strategic use of this practice. The first exemplar, the Tutor 7-Writer 7 case (see table 8), characterizes a planning conversation in which the tutor and supervisor engage in detailed planning—much of which the tutor covers during the consultation. The second example, the Tutor 4-Writer 4 case (table 9), examines a planning meeting in which the tutor and supervisor prepare vaguer plans, and the ensuing consultation seems unfocused. The third exemplar, the Tutor 1-Writer 1 case (table 10), illustrates a tutor who appears to balance pre-consultation plans and the writer’s concerns, establishing and covering a well-prioritized, shared agenda.

Exemplar 1: Detailed Tutor-Supervisor Planning

In this study, very detailed pre-consultation planning—particularly with inexperienced tutors—appears to contribute to tutors taking more control over their consultations. One quantitative clue to this scenario is a higher-than-average planned/covered alignment percentage. For instance, Tutor 7, a first-semester tutor, makes specific, comprehensive plans with a supervisor and later directs most agenda-setting and instructional phases of his session, repeatedly relegating the writer’s concerns to a lesser status than his plans. During teaching phases of the consultation, the tutor does not deviate much from his instructional plan, and he redirects or only briefly addresses the writer’s proposed agenda items. In this case, roughly two-thirds of the tutor’s planned agenda items receive coverage during the instructional phase of the consultation (higher than the average of about half).

Tutor 7 engages in a longer-than-average preparation conversation that produces a detailed consultation plan—a total of eight specific writing issues. First, he mentions that the writer’s main concern on the intake form is the grammar in his reading response document. Disagreeing with this priority, the tutor tells his supervisor, “The main thing I need to focus on here is, um, like, the rhetorical situation.” With the advisor, Tutor 7 highlights the writer’s key problem—a failure to answer the prompt. They discuss concrete options for supporting the writer’s revision process, such as using the center’s “bottom-line-up-front” handout to explain how to foreground claims in a thesis and topic sentences. They also discuss how generating a reverse outline might address the draft’s organizational problems.

Entering the consultation equipped with a comprehensive plan and presuming that the writer lacks awareness of his writing issues, Tutor 7 directs or redirects most agenda-setting and instructional phases of the consultation. The writer, a multilingual international graduate student with prior experience at the center, presents some agenda items but largely defers to the tutor. Marking the first agenda-setting phase, for instance, the tutor begins by introducing his planned areas of concern. When the writer interrupts to articulate his interest in discussing content development and grammar, the tutor explicitly opposes these proposed agenda items, redirecting the focus: “Uh, so, I would actually say, rather than adding more points, I think you have a lot of points here, and, like, a lot of good information. Uh, what I think is more important is to, kind of, like, reorganize them in, in, like, like, based on what the prompt is asking.” The writer responds with a brief, “Ok,” followed by the tutor asking about the context of the assignment.

Soon after, mirroring his supervisor’s advice to focus on structure, Tutor 7 proposes discussing the “bottom-line-up-front” notion and handout. He asserts, “Uh, I think, the thing that could, like, help your essay the most, um… is the idea of, um, bottom line up front… um, where we have one of our handouts that we love to use, um…” As Tutor 7 explains the benefit of placing key ideas in primary positions in the text, Writer 7 mainly provides brief backchannel. He interjects at one point to inquire again about adding details: “They’re asking about a minimum seven hundred words, so, I don’t know if I should add more, or just keep—I don’t know.” Maintaining control over the agenda, the tutor reassures the writer that they will likely add content while rearranging paragraphs. He resumes discussing structure, reinforcing his planned agenda: “I say, I say let’s start by reorganizing the paragraphs, and I bet you’ll find that, like, once you do that, then you, you’ll find there’s, like, more you can say about it.” Again, dismissing the writer’s proposed agenda items, Tutor 7 positions the writer as a novice whose articulated concerns hold lesser value.

Later, the tutor takes the lead once more by proposing another pre-planned agenda item:

So, so, now, I think, the best way to go, is to, kind of, like—um, and, and, like, once again, uh, feel free to stop me if you’d rather do something else […] you, kind of, have these ideas… And, now, you want to create paragraphs that will, like, support these ideas, and, like, kind of, go into more detail.

While the tutor offers a perfunctory opening for the writer’s agenda here, Writer 7 passively accepts the tutor’s recommended course of action. In a similar way, later, Tutor 7 returns to another planned agenda item, directing the next activity: “So, I’m thinking, kind of, leave these paragraphs, but, like, also, we’ll work on putting topic sentences for them,” with the rationale that “now I understand what you’re doing with these paragraphs, it was, kind of, hard to tell at the time because of the lack of topic sentences.” The writer again accepts the shift in the consultation focus without objection, and they begin developing topic sentences.

With just a few minutes remaining, Tutor 7 returns to the writer’s primary concern from the intake form—one the writer reiterated early in the consultation. The tutor asks, “Do you want to spend some time—I mean, we have, like, six or seven minutes left. Do you want to spend some time talking about grammar a little bit?” Finally giving credence to the writer’s main concern, the tutor offers to address grammar for a few minutes. After identifying and correcting various surface-level errors, though, he admits that his grammatical instruction amounts to mere editing, and he suggests that they move on. The writer agrees, stating that generating ideas has been useful.

Overall, this tutor appears committed to executing his initial plan for the consultation, perhaps because he lacks tutoring experience and views the detailed plan he developed with his supervisor as an unalterable consultation blueprint. Problematically, he assumes that the writer is unaware of his writing problems, and he directs most of the agenda and teaching phases instead of prioritizing the writer’s concerns.

Exemplar 2: Vague Tutor-Supervisor Planning

Unlike very detailed pre-consultation planning, when tutors and supervisors and/or tutors and writers sketch very general or vague plans, the results are higher-than-average proposed/covered alignment percentages; these sessions tend to be more reaction-driven consultations. For instance, Tutor 4 develops a broad plan for the consultation with his supervisor with a total of five general writing items (fewer than the average). During this consultation, the tutor and writer do not engage in substantive agenda setting; instead, they spontaneously propose agenda items throughout the appointment and address those items as they arise. This approach, while strongly aligning proposed and covered agenda items, undermines the goal of building a cohesive, well-prioritized session that balances tutor, supervisor, and writer concerns. In this way, this consultation lacks the key benefit of reading and planning ahead: carefully considering complementary topics and actions that writers might most benefit from addressing. Less-developed planning and consultation agenda negotiation may create a reactive tutoring session that presents disconnected impressions of the text rather than an organized, well-prioritized, memorable consultation.

In his planning meeting, Tutor 4, an undergraduate tutor concluding his first year of tutoring, and the supervisor discuss the writer’s research paper. Evaluating the paper as “pretty close” to completion, the tutor points out a missing connection between the writer’s “overarching theme” and conclusion. He highlights the rubric’s requirement that the paper articulate a novel claim, and he assesses the argument as an unelaborated, “kind of, like, a standard, um… kind of, opinion.” The tutor proposes addressing one broad writing issue: clarifying the novelty of the writer’s main argument by distinguishing it from secondary-source claims. They do not discuss concrete actions or resources to utilize during the appointment.

The ensuing consultation reflects the vagueness of this pre-consultation meeting. The tutor opens the consultation with the writer, a repeat visitor to the center who is an international undergraduate in her first year, by eliciting her concerns: “Um, real quickly before we get started, um, I had a couple of things that I wanted to go over with you, but I wanted to ask, in terms of setting an agenda, um, did you have anything in mind, like, specifically, you wanted to go over in the paper, or, like, a specific section?” Couching the invitation to shape the agenda in his own pre-determined instructional plan, the tutor limits the writer’s contribution to the agenda by asking her which section she wants to review. The writer points to the section of the paper that most concerns her, and the tutor agrees without clarifying what writing issues require attention: “Um, so, you just wanted to go over that, and see if that, kind of, flows, and your argument’s clear...” His follow-up question, “Just, kind of, general quality?” launches a broad, poorly defined agenda that parallels the unclear plan generated with his supervisor.

This incomplete agenda-setting stage prompts a conversation that primarily alternates between the writer’s descriptions of her intentions and the tutor’s reactions to the paper. Rather than a rich, dialogic interplay centered on related global writing issues, each interlocutor takes extended conversational turns, explaining their perspectives on the paper’s claims before asking the interlocutor a broad question. For instance, after a protracted commentary on the writer’s argument, Tutor 4 asks a general question: “Ok, so first paragraph: what do you think?” The writer replies to this broad question with a lengthy explanation of her paragraph’s goals, which the tutor accepts with backchannel before engaging in his own extended explanation of his confusion. He then proposes another vague agenda item discussed with his advisor: “Um… so, what I would suggest is we can try to work on, kind of, expanding this connection in this last paragraph.” The writer passively accepts this recommendation, and they resume their pattern of alternating lengthy conversational turns that analyze the overall argument.

About halfway through the consultation, Tutor 4 presents the writer with several options for what to discuss next. The writer responds in general terms: “Um, I also wanted to go over previous… sections.” The tutor does not ask her to specify which sections or writing issues she wants to consider; instead he refers to the abstract and introduction sections. They resume alternating between extended conversational turns, offering disconnected impressions, ideas, and suggestions for the paper.

My analysis of the Tutor 4-Writer 4 consultation suggests that during read/plan-ahead consultations, a vaguely planned agenda paired with a poorly negotiated agenda may lead to a reaction-driven consultation. An undeveloped plan may reflect the tutor’s uncertainty about appropriate instructional topics and techniques. Such ambiguity might signal the tutor’s need for more specific direction and guidance from a supervisor or colleague. In this case, a vague tutor-supervisor plan combines with an unfocused tutor-writer agenda to set up a disorganized, disjointed consultation. This consultation broadly addresses various writing issues—thesis, introduction, content development, organization, and bottom-line-up-front—but the absence of meaningful back-and-forth dialogue between the interlocutors implies a lack of cohesion and comprehensibility that may inhibit the writer’s revision or growth.

Exemplar 3: Balanced Planning and Consultation Agendas

In the most qualitatively effective consultations in my study, tutors develop short but precise lists of writing items with supervisors and, later, elicit and incorporate into the agenda several of the writers’ concerns. These tutors demonstrate how the read/plan-ahead model might be used constructively to prepare tutors for consultations without undermining the writing-center ideal of establishing shared agendas. For example, Tutor 1, a first-semester tutor in the literature MA program with three years of high-school teaching experience, consults with Writer 1, a multilingual international graduate student in his first visit to the center. In the consultation, they establish alignment percentages that fall slightly below the averages in this study, indicating the tutor’s responsiveness to the writer’s agenda.

In a longer-than-average pre-consultation conversation, the tutor, supervisor, and researcher generate a list of five specific writing items to address. They first speculate about whether the writer understands the purpose and trajectory of his literature review. The tutor plans to prompt the writer to explain the “main news” of each literature-review subsection. They also discuss missing and unclear research-novelty moves. Identifying concrete supporting resources, the tutor mentions the center’s literature-review handout with examples showing how literature reviews craft arguments. This planning conversation robustly analyzes the writer’s text, and the tutor proactively strategizes specific writing topics and corresponding instructional actions.

Although the tutor enters the consultation with a concrete plan, he begins by meaningfully soliciting the writer’s concerns: “So, I think, the first thing we should do is set an agenda about what we want to talk about today. So, were there any, uh, questions, comments, issues, uh, that you wanted to look at in this literature review?” In response, the writer proposes that they discuss whether his literature review includes sufficient content and organizes ideas appropriately. Listening attentively, Tutor 1 agrees with these writing areas, adding one of his own planned items: discussing the key claim the audience should understand. This early agenda-setting discussion maintains equilibrium between the tutor’s plan and the writer’s expectations for the session—a balance the tutor continues as the consultation progresses.

Later, echoing a concept discussed during his planning meeting, the tutor connects his own and the writer’s agendas with a specific, guided question: “So, is the literature review—what, what is the purpose of the literature review in, kind of, the larger project for you?” The writer begins explaining the project’s main foci, prompting the tutor to address the document’s subheadings and his previously articulated concern about the literature review’s structure. Tutor 1 explains, “The reason I’m doing this is so that, you know, because you wanted to talk about structure, and I agree that’s definitely something very important. So, I definitely wanted to figure out, kind of, what the, the main ideas you’re communicating [are].” Harkening back to the writer’s concern about the paper’s organization reveals the tutor’s commitment to addressing the writer’s proposed agenda—an act that links the tutor’s plan with the writer’s concerns. This apparently intentional effort to reconcile his own and the writer’s priorities shows that tutors who plan ahead can still place writers at the center of consultations; they can make productive, meaningful associations between supervisor, tutor, and writer concerns.

Again linking his plans with the writer’s concerns, the tutor then presents a new direction for the second half of the appointment: “So, um, what I want to do for the next, I guess, twenty-five minutes is, um, talk about… maybe how we can structure this so that it’s more of, it’s more of an argument, um… What, what do you know about literature reviews? What experience do you have about literature reviews? Have you written any before?” Here, Tutor 1 segues from the writer’s interest in structure into his plan to discuss how literature reviews craft arguments. The tutor’s open-ended, guided questions encourage the writer to articulate his understanding of a literature review and reveal areas of confusion. As the writer answers these questions, Tutor 1 broaches an instructional action discussed with his advisor—reviewing the literature-review handout. A logical outgrowth of their conversation about the genre’s structure, the tutor shows a literature-review example, and they collaboratively mark similar rhetorical moves in the writer’s draft.

The case of Tutor 1 reveals how tutors who read and plan ahead can balance their instructional plans with writers’ concerns by beginning with dedicated agenda-setting exchanges and drawing on but not pushing their own planned agendas. Tutor 1 takes advantage of the read/plan-ahead model, preparing focused, research-based plans with a knowledgeable supervisor—but he does not follow that agenda strictly. Instead, he elicits the writer’s concerns and draws explicit connections between his own plans and the writer’s agenda. After a rich, dialogic consultation, one might expect the writer to retain both the tutor’s advice and his ownership over the text.

Discussion

This exploratory, mixed-methods study considers how the read/plan-ahead method may be used in writing centers. Although limited to thirteen tutor-writer cases with undergraduate and graduate tutors in their first three semesters of tutoring, this study offers a glimpse into the affordances and constraints of this emerging practice. Unsurprisingly, all thirteen tutors introduce some of their planned instructional topics and actions into their consultations; this finding demonstrates that tutors who plan for sessions with more-experienced supervisors carry some of those plans into their consultations. Thus, the read/plan-ahead model achieves its intended goal of allowing tutors to strategize some direction for their consultations. In sessions with advanced writers from unfamiliar fields, many tutors would welcome pre-consultation planning and guidance from more-experienced supervisors and colleagues.

Nonetheless, only about half of the writing items tutors and supervisors plan to for consultations arise during tutor-writer agenda setting, and only about half of planned items receive coverage during instructional phases of consultations. Moreover, roughly one-third of writing items appear across tutors’ planned, proposed, and covered domains, suggesting that these tutors do request and prioritize writers’ agenda items, abandon their plans when writers resist their agendas, and address new writing items as consultations progress. Tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method do not appear to fervently push their planned agendas once they enter writing consultations. These quantitative results might reassure writing center administrators who are hesitant about this tutoring model: tutors who prepare for consultations do not ignore or disregard writers’ agendas and priorities. Indeed, tutors who plan for consultations can engage in the “active listening” Anglesey and McBride and others advocate and can remain collaborative peers rather than directive instructors.

While my quantitative findings suggest most tutors in this study balance planned, proposed, and covered agendas, my qualitative findings complicate these results. My qualitative analyses reveal differing degrees of receptiveness to writers’ agendas and varying abilities to address coherent agendas. In this portion of my analysis, we observe how one tutor whose alignment percentages fall slightly below the study’s alignment averages exhibits skill in connecting his planned agenda with the writer’s concerns. We also observe a tutor whose planning conversation addresses broad writing issues as he ultimately engages in a reaction-driven consultation, and we see how a less-experienced tutor who engages in quite detailed planning pushes his plans over the writer’s concerns. These cases reinforce the importance of limiting the number of planned writing topics and actions to avoid placing too much pressure on tutors to cover a long list of specific writing issues. In addition, these cases point to the significance of regularly observing tutors as they use the read/plan-ahead method; such observations should ascertain how tutors manage conflict between their planned agendas and writers’ articulated concerns. Conducting consultation observations and meeting with tutors afterward to analyze observation notes may enable administrators to pinpoint examples of successful and ineffective uses of this practice.

Ultimately, the question of why some tutors enact their plans more stringently than others remains unanswered. Without systematically analyzing a larger sample of planning meetings and consultations and interviewing tutors about their intentions, one cannot definitively state what factors influence the degree of correspondence between tutor’s plans and proposed and covered items in their consultations. Determining factors may include the nature of pre-consultation meetings, consultation contexts and dynamics, and tutor and writer experience levels and traits. Regardless of what affects alignment across domains, decades of writing center scholarship on the pedagogical value of tutors and writers collaboratively building consultation agendas suggest that tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method should never strictly enact their pre-planned agendas at the expense of writers’ concerns. Instead, based on the results of this exploratory study and my firsthand experience working in a center that uses the read/plan-ahead method, I propose that tutors should use this method to formulate tentative instructional plans and then, present those plans to writers for collaborative modification. Although students come to writing centers pursuing writing advice, they simultaneously seek and deserve to exercise autonomy in their writing process. The read/plan-ahead model does not inevitably threaten this ideal; if tutors’ preparation sessions begin with the concerns writers list on their intake forms and formulate tentative agendas that complement writers’ concerns, the read/plan-ahead method can reinforce the traditional principle of placing writers at the center of consultations.

Because tutoring is a complex endeavor, no universal degree of alignment exists across planned, proposed, and covered domains in read/plan-ahead consultations. Tutors and writers address and ignore instructional topics and actions for various reasons—either deliberately or inadvertently. Tutors may plan to discuss specific topics and corresponding actions, but once they begin negotiating agendas with writers, they may decide to give other topics and actions precedence. In other cases, tutors may intentionally abandon planned agenda items, forget to suggest and address planned items, or reject planned items when writers challenge them. Tutors and writers may also agree to cover certain topics or actions but find they lack time to address the items during teaching phases of their consultations. In short, tutors and supervisors should not expect or strive for total alignment across all three domains of planned, proposed, and covered agendas. Instead, the goal should be approximate correspondence between high-priority topics and actions that tutors plan, negotiate with writers, and attend to during consultations. Ultimately, administrators and tutors should always remember the philosophy underpinning the read/plan-ahead method: tutors can more effectively guide consultations (especially with advanced writers from unfamiliar fields) if they carefully prepare cohesive agendas—and then present those plans to writers for revision.

Conclusion

While this study of the read/plan-ahead tutoring method remains limited by the number of tutor-writer cases and the context of this writing center, its conclusions offer some direction for administrators. One takeaway is that planning too much or too little may set tutors up for consultations that fail to negotiate and carry out well-prioritized, mutually accepted agendas. Planning lengthy, detailed lists of concrete agenda items might place undue pressure on tutors to accomplish too much during consultations and could lead tutors to push their planned agendas over writers’ concerns. On the other hand, vaguely planned agendas may provide insufficient guidance for tutors—especially inexperienced tutors or tutors working with advanced writers from unfamiliar disciplines; ambiguous plans may lead to disorganized, reaction-driven consultations.

Future research on the read/plan-ahead model should examine some common concerns articulated by my survey respondents about this practice. One frequently mentioned fear about this emerging model from my survey is that reading and planning in advance stifles peer dialogue—a main benefit of writing center consultations. A related concern is that tutors who read ahead might focus disproportionately on lower-order concerns or editing. Studies comparing read/plan-ahead consultations with traditional consultations might examine some of these apprehensions. For instance, a study might compare whether tutors in read/plan-ahead consultations talk more often or more authoritatively than tutors in traditional consultations. Another study could examine whether tutors who read and plan ahead focus more of their sessions on editing than tutors in traditional sessions. Some survey respondents also worry that tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method may enter consultations in a hierarchically different position than tutors who read student writing during consultations; a similar concern is that writers may expect tutors who read and plan ahead to act as teachers who guarantee “perfect” writing. To test these assumptions, surveys or interviews with writers participating in both read/plan-ahead and traditional consultations could compare writers’ perceptions of tutors’ roles and their expectations of what tutors should provide during consultations.

Another avenue for future research might consider the role of tutor identity in read/plan-ahead consultations. One unanswered question from this study is whether certain tutors might benefit more from the read/plan-ahead method than others; for instance, tutors who suffer from anxiety or have specific learning differences or neurological conditions might benefit from using this tool more than tutors without these traits. Because this study did not collect data on participating tutors’ traits and neurological conditions, one can only speculate about whether the efficacy of this tutoring method depends on tutors’ identity. Future research on the read/plan-ahead method might more fully account for the role of tutor identity in these types of consultations. For example, a survey study could examine whether tutors with specific traits or conditions express higher levels of preference for the read/plan-ahead method than tutors without the same traits or conditions. To examine whether tutor identity influences the efficacy of the read/plan-ahead method, an observational study could collect data on tutors’ traits and conditions, record the tutors in traditional consultations and in read/plan-ahead consultations, and compare the consultations in terms of tutors’ reported levels of anxiety or stress, tutors’ and writers’ satisfaction with consultations, and other metrics that determine the success of tutoring sessions.

In the absence of evidence on these matters, administrators may confront common concerns about the read/plan-ahead model in tutor professional development. Administrators should emphasize that consultation preparation should always start with writers’ listed concerns on intake forms, and consultations must always begin by eliciting and prioritizing writers’ concerns. Tutors might practice strategies for explicitly connecting their plans with writers’ concerns. They might role play common agenda-negotiation scenarios and rehearse how to manage tension between tutors’ and writers’ agendas. While the read/plan-ahead method does not require experienced tutors to meet with supervisors to plan for consultations, supervisors should regularly observe their tutors’ read/plan-ahead consultations, note how tutors balance and connect their plans with writers’ agendas, and discuss with tutors how to navigate agenda-based conflicts.

Administrators can use the read/plan-ahead model and maintain a culture of collaboration and peer dialogue in their center. Center websites and outreach materials should clarify that although tutors prepare for consultations, writers’ priorities always take precedence, and tutor-writer conversation remains central to all consultations. Administrators should clarify how much of a writer’s text can typically be covered during appointments and should explain what types of writing issues tutors prioritize—higher-order global concerns. Outreach materials should also articulate that tutoring always aims to support writers’ processes, not create perfect documents.

Ultimately, deciding whether the read/plan-ahead model can be used productively in a center requires understanding local tutor and writer populations and adapting the model to meet student needs. This study’s most collaborative, coherent read/plan-ahead consultations balance tutor and writer agendas. These cases begin with robust tutor-supervisor planning conversations that consider writers’ listed concerns, identify a few related global writing topics and actions, and generate guiding questions to ask writers. Subsequent consultations involve substantive agenda-setting exchanges with writers in which tutors genuinely elicit writers’ concerns, explicitly link their plans with writers’ agendas, and change direction when their plans conflict with writers’ agendas. Like any writing consultation, the read/plan-ahead model works best when tutors remember to place writers at the heart of building, revising, and enacting consultation agendas.

Notes

“Multilingual international students” are international students for whom English is an additional language.

One potential limitation to the researcher participating in planning conversations is that tutors may have felt pressured to execute plans because the researcher observed their subsequent consultations. Future research might examine correlations between participants in planning conversations and tutors’ commitment to pre-consultation plans.

This study uses elements of Tannen’s (1989) transcription method:

. sentence final falling intonation

, clause-final intonation (‘more to come’)... a pause of 1⁄2 second or more (with brackets indicating the number of seconds)

.. perceptible pause of less than 1⁄2 second

‘‘ dialogue

The outside rater brought extensive tutoring and administrative experience from another writing center: serving as a graduate writing center administrator, transcribing one hundred writing center research files, training writing center consultants, and writing an in-house writing center handbook.

“Domestic students” are students born in the United States whose first language is English.

Works cited

Anglesey, Leslie, and Maureen McBride. “Caring for Students with Disabilities: (Re)defining Welcome as a Culture of Listening.” The Peer Review, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019, https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/caring-for-students-with-disabilities-redefining-welcome-as-a-culture-of-listening/. Accessed 2 June 2022.

Black, Laurel Johnson. Between Talk and Teaching: Reconsidering the Writing Conference. Utah State University Press, 1998.

Caposella, Toni-Lee. Harcourt Brace Guide to Peer Tutoring. Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1998.

Clark, Irene. “Perspectives on the Directive/Non-Directive Continuum in the Writing Center.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 22, no. 1, 2001, pp. 33–58.

Cogie, Jane. “Peer Tutoring: Keeping the Contradiction Productive.” The Politics of Writing Centers, edited by Jane Nelson and Kathy Evertz, Boynton/Cook Publishers-Heinemann, 2001, pp. 37-49.

Ewert, Doreen. "Teacher and Tutor Conferencing." The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching. 2018, pp. 1-7.

Gillespie, Paula, and Neal Lerner. The Allyn and Bacon Guide to Peer Tutoring. Allyn and Bacon, 2000.

Harris, Muriel. “Collaboration Is Not Collaboration Is Not Collaboration: Writing Center Tutorials vs. Peer-Response Groups.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 43, no. 3, 1992, pp. 369–83.

---. Teaching One-to-One: The Writing Conference. The WAC Clearinghouse, 1986.

Kent, Richard. “SLATE Statement: The Concept of a Writing Center by Muriel Harris.” Guide to Creating Student-Staffed Writing Centers, Grades 6-12, edited by Richard Kent, Peter Lang, 2006, pp. 151-62.

Lee, Cynthia. (2015). “More Than Just Language Advising: Rapport in University English Writing Consultations and Implications for Tutor Training.” Language and Education, vol. 29, no. 5, 2015, pp. 430-52.

Macauley, William. “Setting the Agenda for the Next 30 Minutes.” A Tutor’s Guide: Helping Writers One to One, edited by Ben Rafoth, Boynton/Cook Publishers-Heinemann, 2000, pp. 1-8.

Mackiewicz, Jo. “Hinting at What They Mean: Indirect Suggestions in Writing Tutors' Interactions with Engineering Students.” IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, vol. 48, no. 4, 2005, pp. 365-76.

Mackiewicz, Jo, and Isabelle Thompson. “Instruction, Cognitive Scaffolding, and Motivational Scaffolding in Writing Center Tutoring.” Composition Studies, vol. 42, no. 1, 2014, pp. 54–78.

---. Talk About Writing: The Tutoring Strategies of Experienced Writing Center Tutors. Routledge, 2018.

Newkirk, Thomas. “The First Five Minutes: Setting the Agenda in a Writing Conference.” The Allyn and Bacon Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice, edited by Robert Barnett and Jacob Blumner, Allyn and Bacon, 2001, pp. 302-15.

Nickel, Jodi, et al. “When Writing Conferences Don’t Work: Students’ Retreat from Teacher Agenda.” Language Arts, vol. 79, no. 2, 2001, pp. 136–47.

Reigstad, Thomas, and Donald McAndrew. Training tutors for writing conferences. National Council of Teachers of English, 1984.

Reinking, Laurel. Writing Tutorial Interactions with International Graduate Students: An Empirical Investigation. 2012. Purdue University, PhD dissertation.

Ryan, Leigh, and Lisa Zimmerelli. The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. 6th ed., Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Scrocco, Diana Awad. “Reconsidering Reading Models in Writing Center Consultations: When is The Read/plan-ahead Method Appropriate?” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 14, no. 3, 2017, pp. 48-64.

Severino, Carl. “Reviewed Work: A Tutor's Guide: Helping Writers One to One by Ben Rafoth.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 22, no. 1, 2001, 104-9.

Tannen, Deborah. Talking Voices: Repetition, Dialogue, and Imagery in Conversational Discourse. Vol. 26. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Thompson, Isabelle. “Scaffolding in the Writing Center: A Microanalysis of an Experienced Tutor’s Verbal and Nonverbal Tutoring Strategies.” Written Communication, vol. 26, no. 4, 2009, pp. 417-53.

Thompson, Isabelle, et al. “Examining Our Lore: A Survey of Students’ and Tutors’ Satisfaction with Writing Center Conferences.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 29, no. 1, 2009, pp. 78-105.

Thonus, Terese. “Tutor and Student Assessments of Academic Writing Tutorials: What Is ‘Success’?” Assessing Writing: An International Journal, vol. 8, no. 2, 2002, pp. 110-34.

Valentine, Kathryn. “The Undercurrents of Listening: A Qualitative Content Analysis of Listening in Writing Center Tutor Guidebooks.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 36, no. 2, 2017, pp. 89-115.

Walker, Caroline. “Teacher Dominance in the Writing Conference.” Journal of Teaching Writing, vol. 11, no. 1, 1992, pp. 65-87.

Weigle, Sara Cushing, and Gayle Nelson. “Novice Tutors and Their ESL Tutees: Three Case Studies of Tutor Roles and Perceptions of Tutorial Success.” Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 13, no. 3, 2004, pp. 203-25.

Williams, Jessica. “Tutoring and Revision: Second Language Writers in the Writing Center.” Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 13, no. 3, 2004, 173–201.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix c