The Writing MAP: A Primer for Facilitating Motivational Habits in the Writing Center

Elizabeth Buskerus Blackmon

St. Louis Community College– Meramec

ebusekrus1@stlcc.edu

Abstract

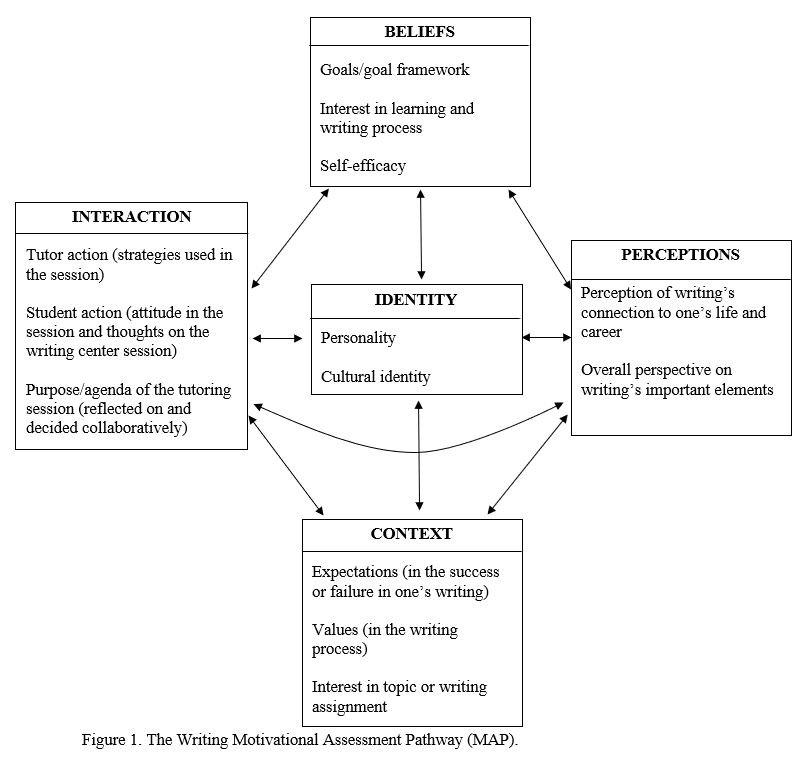

Motivation interconnects with many aspects of a student’s higher education journey; a student’s goals, self-efficacy, interests, and prior experiences affect their level of motivation and engagement in a writing center session. This primer discusses the multidimensional nature of motivation and its relation to identity. Through an exploration of the literature, the author designed a heuristic called the Writing Motivational Assessment Pathway (MAP). This tool focuses on understanding students’ motivations, engaging students more in their writing process, and encouraging their development as writers. The five components of the Writing MAP—identity, beliefs, perceptions, context, and interactions—work toward understanding a student’s motivational profile and pairing strategies that connect with each student. This article discusses how to identify students’ motivational habits through the Writing MAP to help students establish effective writing habits and foster self-regulation. This heuristic continues to be refined at the community college level.

As writing center professionals, we see daily how students’ perspectives about writing drive their motivation to write, and these drives become habits and practices which they ingrain into their process. Motivation depends on a person’s perspectives, desires, and the context of a scenario (Dresel and Hall 58-59). In other words, a student’s beliefs, wants, and needs influence that student’s motivation; additionally, the environment (classroom, writing center, home, etc.) affects the direction and intensity of a student’s motivation. At the college level, this framework relates to students’ prior knowledge and experiences, as well as students’ identity. Motivation’s interconnectedness with cognition, emotion, and behavior should encourage writing centers to consider how this concept impacts our work and how we can reflect on and facilitate motivational habits in the writing center. Helping students to discover a fuller version of their identities as writers starts with understanding their motivations. Encouraging students to connect with their writing and to understand who they are as writers helps them to nurture their writing skills.

Jo Mackiewicz and Isabelle Thompson consider motivation to be a crucial aspect of writing. They emphasize how “motivation – the drive to actively invest in sustained effort toward a goal – is essential for writing improvement” (“Motivational Scaffolding” 38). Mackiewicz and Thompson study this process of cognitive and motivational scaffolding techniques in tutoring sessions (“Instruction” 59-64). Their depiction of motivation boils down to three core terms: interest, self-efficacy, and self-regulation (Mackiewicz and Thompson, Talk about Writing 25-26). According to Mackiewicz and Thompson, interest can increase focus on a task; self-efficacy (or one’s confidence level) can cause students to perceive an assignment as more challenging or easier than it is; and self-regulation (behaviors such as goal setting and metacognition) can lead to high degrees of performance. Each of these terms connect back to significant principles shown in the literature (as noted in a later section)—the effects of the learning environment, the students’ goals, and the interest level of students in these academic matters.

Although writing center tutors are not trained professional psychologists or counselors, they can work toward understanding motivation, identifying common motivational habits during sessions, and collaborating with students to reflect on writing habits. Motivation is a thread in the tutoring session, whether the tutor recognizes it or not. This concept impacts how the student approaches the assignment and how engaged the student is within the writing center. Students incorporate their identity, beliefs, perceptions, and context into their writing process, but they may not be aware of these elements and use them with intentionality. In this article, I first conceptualize motivation through the relevant scholarship on this topic, and then, I describe a heuristic I designed for tutors. This heuristic, named the Writing Motivational Assessment Pathway (MAP), is a way to understand this scholarship in a more comprehensive manner and to apply motivational concepts within the tutoring session.

The Writing MAP is a training tool that emerged from studying how the literature on motivation concepts can work holistically in a writing center setting. As I researched and explored motivation informally in a community college setting, I began to see how motivation functions in tutoring sessions and to work on understanding its applications in tutor training. From this research, I designed the Writing MAP, which focuses on understanding students’ motivations, engaging students more in their process, and encouraging their development as writers. This analysis allows the tutor to see the student’s motivational strengths and obstacles and to collaborate with the student, pairing strategies that connect with these strengths and lessen these obstacles. This article will primarily center on identity as a core aspect of motivation. Understanding the intersectionality and formation of students’ identities, especially for underrepresented writers, can help tutors to visualize their motivations when writing.

Defining Motivation and Identity: A Multidimensional Approach

Markus Dresel and Nathan C. Hall emphasize the recursive nature of motivation. They define motivation as “the processes underlying the initiation, control, maintenance, and evaluation of goal-oriented behaviors” (59). They analyze motivation in terms of the individual, the learning context, and the individual within that context. The individual’s overall framework of motivation impacts how a student perceives a task and what their predispositions are when it comes to setting goals. When this individual is placed in a learning environment, they create goals; John G. Nicholls connects these achievement goals directly with behaviors (328-329). The student’s goals are further impacted by their self-efficacy (Bandura) and their overall perceptions, also defined as self-determination theory: autonomy, belonging, and competence (Luyckyx et al.). How the authority figure (in this case the tutor) constructs the environment also figures into the equation. In this context, the student considers the expectancies for achievement and their overall values, implements effort accordingly, and then assesses the results of their efforts. Robert G. Isaac et al. emphasize how these expectancies for success or failure impact students’ actions, and Maarten Vansteenkiste et al. focus on how students’ values connect with the students’ identities. Roy Baumeister adds to this definition of motivation, showing it as a desire to alter oneself or one’s situation (1-2), and Johnmarshall Reeve focuses on motivation as a process of “seeking” (32). Identity becomes a point of emphasis within motivation theory. James E. Marcia discussed identity in terms of two spectrums: exploration and commitment. As students’ identities change along these spectrums, their motivations change as well.

Other scholars center their motivation definitions around the binary of extrinsic and intrinsic. Students with extrinsic motivation complete tasks for a reward or to evade a penalty; those with intrinsic motivation do a task for pleasure, enjoyment, or reward in the task itself. According to Yi-Chia Cheng & Hsin-Te Yeh, those with intrinsic motivation select more challenging situations, expand their knowledge more when they read, demonstrate more creativity, and show more interest than those with extrinsic (599). In looking through these conceptions of motivation, I noted the essential tenets within the research and grouped this research into five categories: identity, beliefs, perceptions, context, and interactions; these categories became the foundation for the Writing MAP (see fig. 1).

The Emergence of the Writing MAP and its Applications in Tutor Training

Though I will explain each component individually, the Writing MAP should be viewed as recursive, like the writing process. The diagram of the Writing MAP gives a visual representation of these components (see Figure 1). The Writing MAP is an interactive theory, focusing on the student’s and tutor's part in the session and how the actions of both parties interplay. In this section, I will give merit to these concepts, apply them to a community college setting, and provide questions that correspond with the sections of the Writing MAP, which tutors can ask to gauge students’ motivational traits.

Defining Terms in the Writing MAP

The first four categories of the Writing MAP involve analysis of the student. As the tutor becomes more familiar with the student’s motivations, the tutor can better determine an effective course of action within the tutoring session. Below, I explain how these categories came into fruition, how they intersect, and how they are identified during a tutoring session. It is not possible to analyze every factor in a tutoring session, but these five categories can provide guidelines for thinking about motivation during a tutoring session. The Writing MAP helps tutors to navigate issues of identity and motivation in the writing process.

Identity: A Process of Discovery and Choices

Within motivation studies, identity proves an integral concept. According to Bart Soenens et al., identity focuses on “discovery and construction” (438); identity relates to the self but is also contextual, pertaining to different areas of life, such as culture, family life, religion, and career (Zhang 938-939). When a task is congruent with this self-definition, individuals’ motivation to complete that task increases (Oyserman and Destin 1001-1002). If a person must complete a task which aligns with their identity, their motivation is typically high, but for tasks which do not align with a core principle of their identity, their motivation remains low. Put more simply, identity centers on story. Evon Hawkins states: “identity is the story we tell ourselves about ourselves as well as the story we tell others about ourselves, and the story changes based on the situation we find ourselves in” (5). This story can have periods of vacillation and stability throughout one’s life.

Marcia uses the continuums of exploration and commitment to explain identity. Along these two scales are four types of identity statuses: identity achievement (high level of exploration, high level of commitment), moratorium (high exploration, low commitment), foreclosure (low exploration, high commitment), and identity diffusion (low exploration, low commitment). Individuals change in their identity statuses throughout their lives. With identity achievement, people usually present themselves as confident, have good relationships, think complexly, and do not listen to peer pressure as easily as others. Moratorium status shows a similar trend with a high level of self-confidence and not following peer pressure. However, their family relationships are uncertain and not as stable. For foreclosure status, people follow the authoritarian model and often obey their parents or other authority figures on moral matters. Identity diffusion status shows a lower self-esteem and more unstable relationships (Marcia 7159-7163). How a student frames their identity ultimately impacts their effort, interest, goals, and self-efficacy as it pertains to writing.

Identity in the Writing Center

In the Writing MAP, the main concepts under the “Identity” aspect include personality and a collective and cultural identity. Identities can incorporate race, culture, language, disability, religion, and more. While some of these identities can be visible, the nuances of these identities can have unseen implications and motivations. For example, Sacha-Rose Phillips, a writing center tutor, reflects on her tutoring experiences and how she interacts with students based on her identity as an immigrant and ESL student. She assumes that she knows what other ESL students need based on a “shared identity” with them, but she finds: “a variety of factors can influence the extent to which writers feel personally connected to their work, including language identity, social class, and academic discipline” (Phillips 29). Similarly, Hawkins discovers motivation, interest in the assignment and in writing, and core perceptions about writing skills impact students’ identity, in particular their writing identity. Students have varied interest, motivation, and self-efficacy levels that influence their identities, and tutors “can help clients negotiate the complex, interactive web of cognitive, non-cognitive and self-regulatory processes which result in a written product” (Hawkins 5). The writing center can have a direct impact on how this sense of identity relates to writing.

This mission of the writing center connects with who the writing center targets. My writing center focuses on a message of inclusivity, as many others probably do, encouraging students of all cultures, races, and abilities to enter. This message of acceptance can unfortunately become misinterpreted; some students might see the writing center as a remedial space, or they might fear the judgment of the tutors in this place. For these reasons, some students do not visit the writing center or engage in a limited capacity with the writing center. Daisha Oliver, an African American tutor, comments on why more minorities do not visit her writing center: writing in the academic world is considered “white.” Oliver states: “[T]he WC runs the risk of becoming a place that eliminates your culture out of your writing under the pretense of ‘correction.’ ‘Writing white’ often means that minorities resist inserting their authentic selves into their writing and fear visiting the WC” (29). These students think they must dissociate from their identities when they enter the writing center. While writing centers may advocate as a space for all writers, the writing center may be perceived differently by these underrepresented writers. How can we authentically promote this inclusive ideology and help students to showcase their identities in their writing?

Writing centers encounter students with varying goals, needs, and identities, and in these contexts, they have the power to transform mindsets. Though tutors are not counselors, it is important to understand the identities of the students in the writing center because this outlook “can ultimately be a productive use of a session when it helps clients balance their outside obligations with their writing needs” (Hawkins 4). By pinpointing the student writers’ goals, tutors can understand where students are headed, encourage students to reflect on this direction, and complicate the path. Though tutors are only with students for a short period of time, they can significantly impact students’ motivational journeys. Mackiewicz and Thompson highlight strategies that could engage students during a tutoring session, such as validation, encouragement, and focus on the student’s ownership (“Instruction” 63-64). By using these types of techniques, writing center tutors can have an impact on students’ motivation.

At my community college, students come from an assortment of different backgrounds. Many enter directly from the regional public schools. Some are from other countries, speaking a multitude of languages, a diversity that unfortunately can create roadblocks to writing in the English language. Some students have a different way of learning due to a disability, and some are non-traditional students who have waited for a time to come to college. During one day in the writing center, I may hear students tell of their passion for autoimmune diseases, their experience seeing segregation in schools, and their procrastination habits. Each aspect of their identity reveals something that can help our professional tutors connect to them and understand them. By knowing about students’ experiences and perspectives, tutors can provide more relevance in a session. Many identity-focused questions encourage students to share their hobbies, common personality traits, likes, and dislikes to understand more about who they are:

What is a story that defines you?

If somebody were making a movie of your life, what would the title of the movie be?

How would your close friends describe you?

How would you describe your hometown?

What is your favorite book and why?

If you could only do one thing for the rest of your life, what would it be?

What gets you excited to wake up in the morning?

These questions serve as examples; tutors should reflect on what questions are most natural in the moment with a particular student. The other categories of the Writing MAP feed into “Identity” and vice versa. A student’s identity impacts their interest and motivation in writing and their perception of the writing center. A student’s prior academic experiences (and how these experiences affect their outlook) make up identity and become entrenched in the student’s sense of self, showing their perspective of the world.

Beliefs: A System of Goals, Interests, and Confidence

For student writers, their identities come to fruition based on their beliefs about themselves. Albert Ellis et al. show how a system of beliefs can work through the ABC model: “often people experience undesirable activating events (A), about which they have rational and irrational beliefs/cognitions (B). These beliefs lead to emotional, behavioral, and cognitive consequences (C)” (4). People develop a system of rational or irrational beliefs. Irrational beliefs can create cognitively distorted behaviors or consequences.

As seen in Figure 1, another aspect of the Writing MAP delves into students’ beliefs, or their goals, interest in learning, and self-efficacy. Goal setting has been crucial in this area of the Writing MAP. Setting end goals determines the process of learning. Achievement goals move below the surface, shaping mindsets about the process of learning. Nicholls divides achievement motivation into three overarching goal categories: task-mastery, ego-determined goals, and work-avoidant goals. For task-mastery, the goal is to learn; for ego-determined, the goal is to please the teacher; and for work-avoidant, the goal is to commit to the least amount of effort for an activity. Nicholls finds that those with an ego-focused mindset will place themselves in circumstances where they demonstrate high ability in relation to others (330-331).

These goals then connect to a student’s self-efficacy. Self-efficacy signifies their self-perception of their abilities and overall confidence in performing a behavior. Bandura notes a pattern between self-efficacy and failure (“Perceived Self-Efficacy” 121, 130-131). Those with a high level of self-efficacy determine any failures to correlate with effort, whereas those with a low sense of self-efficacy determine failures to correlate with intelligence. Additionally, individuals with stronger self-efficacy determine failures to not be an impossible hurdle (Bandura, “Perceived Self-Efficacy” 121, 130-131). In some capacity, self-efficacy affects students’ goal setting because of self-efficacy’s attentiveness to students’ choices, effort, and responses.

While work-avoidant goals are clearly not beneficial, ego-determined goals are far more complicated. These pursuits show a focus on pleasing an instructor or authority figure, more of an extrinsic determiner. At my community college, one of the students who used the writing center, Stacey, came from a predominantly black high school. Told she would not amount to much in life, she received little encouragement from teachers and counselors in her high school, contributing to her low self-efficacy in academics. How students perceive themselves as writers affects how they approach writing and how motivated they are to write. According to Albert Bandura, the self is “socially constituted” (“Exercise” 77), meaning others can affect one’s identity and self-efficacy levels. The student’s goals, self-efficacy, and interest intersect to create the student’s motivational belief system. Some of these beliefs, ingrained in the student early in their educational journey, can be irrational, based on what others have told the student. In terms of students’ motivational habits with writing, irrational beliefs can lead to low performance, low interest, and procrastination. When tutors ask questions about students’ motivational beliefs, they can assess the root of any irrational beliefs which students may hold:

What were you taught in high school about how to write?

Describe some positive and negative moments you have had with writing. What experiences with writing do you remember most? Consider the experiences in school, at home, and in other environments.

When you receive a writing assignment, how do you determine how much time to put into it?

What are some of your writing goals?

Do you feel like a confident writer? Why or why not?

What is your interest level (with writing in general or with your writing assignments)?

With these inquiries, tutors can unpack how this student thinks and encourage the student to reflect on how past writing experiences may affect what, how, and why the student writes currently. The tutor should not consider this list to encompass all questions to ask nor should the tutor expect to interrogate the writer during the session. Asking one, two, or three questions would be reasonable; the tutor should observe if more are warranted based on the level of engagement during the session.

Perceptions: The Writing Ideologies Which Students Hold Dear

For student writers, writing perceptions relate to a student’s system of ideology. Self-determination theory relates to the autonomy, competence, and relatedness a person considers toward a task. Koen Luyckx et al. claim that the components in self-determination theory are important to sustain to have identity growth (277). What students understand about writing’s core values and about writing’s connection to career and life comes from their overall academic goals and personal identities. Past educational and learning experiences impact how invested and motivated one is in the learning process. Some students who come to the writing center lament that they are not strong writers and feel a sense of disconnectedness from their essay topics and from the overall process. With the example above, when Stacey visited the writing center, she frequently focused on or asked questions about grammar; her high school teachers marked her essays with red marks, using notations like “fragment” and “awkward” throughout the essay. This hyperfocus on one area of writing narrows students’ understanding of writing’s possibilities can create lower confidence, and/or create disconnect between students and their writing. Tutors can increase students’ confidence and help students see the multifaceted, relevant aspects of writing. The following questions correspond to how a tutor can understand student’s writing perceptions more:

How would you define what a good writer is. What attributes do you have of a good writer?

After completing a writing assignment, how do you determine if it was successful?

What successes have you had as a writer?

Describe your writing process from start to finish.

What would make you feel better about how you write?

These inquiries dig into how students perceive their writing process, abilities, successes, and failures. Fostering this vulnerability can lead to insights about the student.

Context: Values and Expectations

In the Writing MAP, contextual motivation depends on students’ thoughts and emotions in connection to the specific assignment. In a community college, students’ expectations of success, values, and interests vary, and each of these aspects adds a layer to their composition. If they expect to fail, value the writing task as only a passing grade, and do not have much interest in the topic, their writing becomes flat and one-dimensional. I have worked with students who struggle with composing a complete sentence or reading a full-length text but value the ability to perform these actions. I have worked with students who have trouble organizing their thoughts and procrastinate on writing their essays, expecting their success to be minimal but not valuing the task enough. Some students have no interest in the topic assigned to them, and their unfamiliarity with the topic then affects their level of self-efficacy in the task. Each of these expectations, values, and interests affects students’ attitude and motivations for that specific task.

Where students place their values and expectations determines how engaged they are in their writing assignment and in the writing center session. These expectations and values play out in expectancy-value theory. Robert G. Isaac et al. position expectancy theory as a process theory, showing how individuals’ beliefs about the task determine their actions (214-215). A student’s expectations regarding if they will succeed or fail in their writing might come from this student’s past academic experiences, such as pressures placed by instructors, parents, and peers; a student’s values in this process connects with their interests (academically and personally) and components of their identity. For example, if a student’s expectations for success are low, and their values focus on correctness and growth as grammatical improvement, that writer’s focus during the tutoring session will be narrow. Maarten Vansteenkiste et al. states: “it is important not only to consider whether people value their task engagement but also the kind of values they are upholding during their activities” (763). The values each student upholds depends on the identities situated in that specific context, as well as the student’s mindset about that task.

Questions can be posed to have the student expand upon the context of that writing assignment and their perception of the writing center:

What expectations have you set for yourself in writing this essay?

Are there any specific writing concerns you have had in the past or the instructor would like you to address?

Where are you in your writing process? What have you been focusing on as you have written?

Are you interested in this writing assignment? Why or why not?

Are you interested in this topic you have chosen for this writing assignment? Why or why not?

What do you expect out of your session today?

What do you think our purpose in the writing center is?

Asking these questions can be telling, explaining why the student has come to the writing center, what they think of the writing center, and what their emphases are for this writing assignment.

Based on these first four aspects of the Writing MAP, how can tutors know the student’s motivational strengths and obstacles? How does the tutor know what to focus on in each session? Applying the Writing MAP involves teaching tutors how to be motivational facilitators.

Tutors as Motivational Facilitators: Another Hat to Wear

Using the Writing MAP can help to make sense of motivation in the writing center; the last aspect of the Writing MAP delves into the interactions in the tutoring session and the choices made regarding strategies and the session’s purpose. This area lends to yet one more hat for tutors, that of motivational facilitators. This hat is central to the other tutoring roles (e.g., writing experts, collaborators, etc.). As an expert, tutors are expected to know more about writing. This role connects to the “Perceptions” area of the Writing MAP; tutors should consider students’ learning and writing perceptions and teach them new approaches to their process based on their perspectives, backgrounds, and experiences. In a collaborator role, the tutor works with the writer, offering suggestions in their writing. Within this role, tutors can encourage student’s interest and values in a task, or the “Context” area of the Writing MAP. Each of these hats intersects in some way with motivation.

The ultimate purpose is not to change the student’s motivational framework but to broaden and deepen it, helping students to see the complexity of choices they have as writers. Mackiewicz and Thompson comment:

Because of the complexity of writing, student writers will not likely improve their writing competence much in a single conference. However, with tutors’ support, they can gain answers to the questions that brought them to the writing center and possibly newly consider their writing practice, so that their writing competence continues to evolve. (“Talk about Writing” 5)

In the writing center, the goal is development, helping students understand their writing identities and processes. Attending to an aspect of a student’s motivation can encourage and engage students more in their writing.

Scholars such Mackiewicz and Thompson offer the theoretical frame for understanding motivation; my goal is to build upon research such as theirs to develop a holistic, practical tool to help tutors determine the support an individual writer might best respond to in the session. The role of motivational facilitators can incorporate many strategies, but in this article, I will focus on two specific intersections, both of which have a dimension of transfer. The first, establishing effective writing habits, is a significant strategy because it leads to the building of reflexive life skills. The second strategy focuses on self-regulation, an important habit that develops confidence.

Identifying a Student’s Motivational Framework to Establish Effective Writing Habits

As indicated earlier, a student’s identity (knowledge, experiences, interests, personality, etc.) affects a student’s motivations to write. Assessing a student’s framework can help the tutor work with the student on establishing more effective writing habits. Using the Writing MAP as a tutor training tool starts with understanding a student’s framework (the Identity, Beliefs, Perceptions, and Context categories of the Writing MAP). Writing center directors can train tutors to listen for irrational belief statements and question students on writing habits. Belief statements start with “I” and usually reinforce a claim about oneself. Irrational beliefs are directly negative statements that depict a fixed mindset about writing, such as “I am a failure at this subject,” or “I cannot complete this task.” For example, one student at my community college writing center, Jill, has made frequent claims that she cannot write. When I questioned her on why she thought this way, she disclosed some learning challenges throughout schooling, mentioning that she had an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) throughout high school to accommodate her specific learning disorder (dyslexia). By knowing this information about her identity, I was able to work with her on how she best learns and help her develop a growth mindset. For Jill, many of her past experiences consisted of teachers commenting on sentence structure issues and formatting. When she failed in these areas, she became discouraged. After being assigned a rhetorical analysis essay in her English Composition 102 class, she wanted to attend to surface-level concerns in her sessions, skirting the essay’s purpose of critically thinking about ethos, logos, and pathos. Together, we worked on discussing the purpose of this type of essay and refocusing her goals on these higher-order concerns. Helping students reflect on their writing beliefs, tutors can encourage students to investigate the “why” behind their motivations, partner with students on how to transform their irrational beliefs, and help them procure more effective writing habits.

On the other hand, finding a student’s motivational strengths involves looking at a student’s positive habits. Perhaps a student has a high self-efficacy and considers any failures as opportunities to learn and grow. Strengths can be displayed as positive statements or positive habits that lead the student toward a growth mindset, or a framework that understands failure as a pathway toward growth and challenge to expand on current skillsets (Dweck 15-17). The tutor should nurture these types of perspectives.

Fostering Self-regulation to Encourage Transferable Skills

This reflectiveness can then help students with transferring their writing skills. Transfer remains a fundamental concept in composition studies and educational psychology and one which intersects with training tutors in the Writing MAP. Bonnie Devet mentions scholarship that highlights how self-regulation, self-efficacy, and reflection helps with the transference of skills for students and for tutors (130-131). Self-regulation extends to control over one’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. Barry J. Zimmerman and Adam R. Moylan show self-regulation as a complex, recursive process, part of which involves reflection (or awareness) (300-305). This self-regulation process gives the student agency and accountability and “determines indirectly changing patterns of poor behavior and positively influence the level of achieved performance” (Daniela 2552). Motivational facilitators can develop effective self-regulation of students’ habits.

Training tutors to facilitate this transfer process can also involve pointed questions. According to Ellen C. Carillo, helping students to transfer their knowledge about writing involves “transforming their prior knowledge rather than applying it” (52). Questions noted in the “Perceptions” section of the Writing MAP investigate a student’s conceptions of their writing habits. For instance, Jill considered grammar to be an important attribute in writing well, and her goal was to pass her English Composition 102 class; I encouraged her to reflect on why she thought grammar was most important and examine other skills that could transfer to various assignments. How students perceive writing affects how they are motivated in approaching each task. While all these questions cannot be asked, the tutor can select a couple questions as a starting point for reflection.

A Writing Center that Motivates

Though students oversee the creation of their own artwork, tutors can help student writers recognize their potential and increase their awareness of their identities. Dresel and Hall motion:

[T]eachers have the potential, and thus the responsibility, to substantially impact the motivation of their students through the use of teaching techniques that maintain and bolster motivation in their students, as well as utilize classroom structures and interaction techniques that promote motivation in their students. (91)

Instructors should consider this weighty mission both to teach students material and to construct a classroom which fosters motivation. A similar charge rests with those in the writing center. While it may not be the writing centers’ sole responsibility to motivate students, constructing a motivational environment can help with student perception of the writing center, development of effective writing habits, and growth as writers.

Establishing relevance in each session could encourage students to rethink their writing processes, commit more effort, and give a clearer purpose to the writing center. John M. Keller denotes relevance as a significant aspect of motivating students. While the environment cannot be fully responsible for the student’s effort, it can be constructed to provide students with “encouragement, scaffolding, and intermediate goal setting” (Keller 9). Rapport with each student allows tutors to know more about the student’s identities (i.e., prior academic experiences, writing expectations, values, and interest level), helping to decide what strategies would work best with the student. Care can best be developed once the tutor has rapport with the student. Self-efficacy should be developed in writing centers because they can act as an avenue to mature students’ sense of self and identity.

Building rapport moves students to share more about themselves, creating more familiarity for the tutor about the student. A greater understanding of the student’s identity can help the tutor to foster more reflectiveness and scaffolding. Two motivational scaffolding strategies that Mackiewicz and Thompson mentioned demonstrate this emphasis on rapport: “demonstrations of concern for students” and “expressions of sympathy and empathy” (“Motivational Scaffolding” 47). With the former technique, the tutor shows a level of care and may inquire as to how the student is doing, and with the latter technique, the tutor may express sympathy about how challenging an assignment is. Using scaffolding to add relevance might involve gauging interests of the students, integrating modeling, and focusing on student choice in what to teach. These relevance activities can lead to students applying their knowledge to real-world situations and to more engagement and a stronger perception of belonging (Gormley et al. 177-179). If the assignment has value to the students, they are more engaged.

This process engages the students in the writing center session and in their own writing journey. By learning the process to identify a student’s motivational habits, tutors work toward understanding students’ identities. Through this process, tutors help students to connect with their writing; the tutor and student collaboratively set an agenda that moves the development of their writing process and their motivation forward. By using the Writing MAP, a writing center that motivates can transform students’ perspectives to help them become more balanced, complete versions of themselves.

Works Cited

Bandura, Albert. “Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning.” Educational Psychologist, vol. 28, no. 2, 1993, pp. 117-148.

Bandura, Albert. “Exercise of Human Agency through Collective Efficacy.” Current Directions in Psychological Science, vol. 9, no. 3, June 2000, pp. 75-78, doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00064.

Baumeister, Roy F. “Toward a General Theory of Motivation: Problems, Challenges, Opportunities, and the Big Picture.” Motivation and Emotion, vol. 40, no. 1, 2016, pp. 1-10, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9521-y.

Carillo, Ellen C. “The Role of Prior Knowledge in Peer Tutorials: Rethinking the Study of Transfer in Writing Centers.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 38, no. 1-2, 2020, pp. 45-71.

Cheng, Yi-Chia, and Hsin-Te Yeh. “From Concepts of Motivation to Its Application in Instructional Design: Reconsidering Motivation from an Instructional Design Perspective.” British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 40, no. 4, 2009, pp. 597-605, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00857.x.

Daniela, Popa. “The Relationship between Self-Regulation, Motivation, and Performance at Secondary School Students.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 191, 2015, pp. 2549-2553, doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.410.

Devet, Bonnie. “The Writing Center and Transfer of Learning: A Primer for Directors.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 1, Fall/Winter 2015, pp. 119-151.

Dresel, Markus, and Nathan C. Hall. “Motivation.” Emotion, Motivation, and Self-regulation: A Handbook for Teachers, edited by Nathan C. Hall and Thomas Goetz, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2013, pp. 57-122.

Dweck, Carol S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Ballentine Books, 2016.

Ellis, Albert, et al. “Rational and Irrational Beliefs: A Historical and Conceptual Perspective.” Rational and Irrational Beliefs: Research, Theory, and Clinical Practice, edited by Daniel David et al., Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 3-22.

Gormley, Denise K, et al. “Motivating Online Learners Using Attention, Relevance, Confidence, Satisfaction Motivational Theory and Distributed Scaffolding.” Nurse Educator, vol. 37, no. 4, 2012, pp. 177-180, doi:10.1097/NNE.0b013e31825a8786.

Hawkins, R. Evon. “‘From Interest and Expertise’: Improving Student Writers’ Working Authorial Identities.” The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 32, no. 6, Feb. 2008, pp. 1-5, wlnjournal.org.

Isaac, Robert G., et al. “Leadership and Motivation: The Effective Application of Expectancy Theory.” Journal of Managerial Issues, vol. 13, no. 2, 2001, pp. 212-226, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40604345.

Keller, John M. Motivational Design for Learning and Performance: The ARCS Model Approach. Springer, 2010.

Luyckx, Koen, et al. “Basic Need Satisfaction and Identity Formation: Bridging Self-Determination Theory and Process-Oriented Identity Research.” Journal of Counseling Psychology, vol. 56, no. 2, 2009, pp. 276-288, doi: 10.1037/a0015349.

Mackiewicz, Jo, and Isabelle Thompson. “Motivational Scaffolding, Politeness, and Writing Center Tutoring.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 33, no. 1, 2013, pp. 38-73, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43442403.

---. “Instruction, Cognitive Scaffolding, and Motivational Scaffolding in Writing Center Tutoring.” Composition Studies, vol. 42, no. 1, 2014, pp. 54-78, http://jomack.public.iastate.edu/.

---. Talk About Writing: The Tutoring Strategies Of Experienced Writing Center Tutors. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2018.

Marcia, James E. “Identity in Childhood and Adolescence.” International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. 1st ed., edited by Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes, Pergamon, 2001, pp. 7159-7163.

Nicholls, John G. “Achievement Motivation: Conceptions of Ability, Subjective Experience, Task Choice, and Performance.” Psychological Review, vol. 91, no. 3, 1984, pp. 328-346, https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.91.3.328.

Oliver, Daisha Denise. “Tutor’s Column: ‘Is Writing for the Majority?: Examining Diversity in the Writing Center.’” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 46, no. 3-4, Nov./Dec. 2021, pp. 27-30, wlnjournal.org.

Oyserman, Daphna, and Mesmin Destin. “Identity-Based Motivation: Implications for Intervention.” Counseling Psychologist, vol. 38, no. 7, Oct. 2010, pp. 1001-1043, doi: 10.1177/0011000010374775.

Phillips, Sacha-Rose. “Tutor’s Column: ‘Shared Identities, Diverse Needs.’” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 42, no. 9-10, May/June 2018, pp. 26-29, wlnjournal.org.

Reeve, Johnmarshall. “A Grand Theory of Motivation: Why Not?” Motivation and Emotion, vol. 40, no. 1, 2016, pp. 31-35, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9538-2.

Soenens, Bart, et al. “Identity Styles and Causality Orientations: In Search of the Motivational Underpinnings of the Identity Exploration Process.” European Journal of Personality, vol. 19, 2005, pp. 427-442, doi: 10.1002/per.551.

Vansteenkiste, Maarten, et al. “Less Is Sometimes More: Goal Content Matters.” Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 96, no. 4, 2004, pp. 755-764, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.755.

Zhang, Li-fang. “Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development.” International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed., edited by James D. Wright, Elsevier, 2015, pp. 938-946.

Zimmerman, Barry. J., and Adam R. Moylan. “Self-Regulation: Where Metacognition and Motivation Intersect.” Handbook of Metacognition in Education. 1st ed.,edited by Douglas J. Hacker et al.,Routledge, 2009, pp. 299-315.

Appendix: Figures

Figure 1: The Writing Motivational Assessment Pathway (MAP)