Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 15, No. 3 (2018)

Composing the Center: History, Networks, Design, and Writing Center Work

William De Herder

Michigan Technological University

wedeherd@mtu.edu

Abstract

Writing center history, design, and pedagogy are often connected and have significant influence over how writing centers work with students. As technologies change, physical locations are altered, pedagogies evolve, and social projects grow, it may become necessary for centers to critically reflect on the history, design, and pedagogical connections within their own workplaces to address misaligned behaviors and designs. This article illustrates how the Michigan Technological University (MTU) writing centers have changed over time and what effects those changes have had on their work. The history was assembled through recovered historical documents and interviews with past center administrators. This evidence is used as a platform for exploring writing center design, drawing from actor network theory, ambient rhetoric, usability design, and multiliteracies theory. The article concludes with an exploration of how other centers might develop flexible writing center designs that may enhance the effectiveness of time with writers and encourage resiliency, resourcefulness, and creativity in center staff. This is accomplished through investigating concepts such as interstitial space, affordances, mapping, and social objects and their influence on work culture.

Introduction

There are innumerable factors that influence the material spaces of writing centers, many of them out of the control of writing center administration. And yet, the material spaces we operate within can have major effects on our work. Years ago, I worked in a university writing center as a professional tutor. All of the learning center support worked together in one big room with rows of rectangular tables with six wheel-less chairs each. New students would invariably sit across from their writing tutors until the tutor asked to sit next to them, making students feel they had done something wrong before the session had even started. Students were not provided handouts very often because most of them were “filed away” in a jam-packed filing cabinet by the front door. The IT department had also made it clear that students were never allowed to put flash drives into any of the computers in case one of them had downloaded a virus. To make things worse, students were not allowed to print anything in the building. The nearest printer for student use was across the street, in the library. Possibly the worst flaw, however, was that the center closed before most non-traditional students could leave their full-time jobs. The program tried to compensate for this by offering asynchronous email tutoring. In these online sessions, tutors were told that they could not write on student papers (just as they could not in their face to face sessions), and so they avoided using comment bubbles or the Track Changes function. Instead, they were instructed to write long lists in a reply email, detailing errors they had found in the writer’s work, each point in the list painstakingly describing the location of each error. (“In the fourth line in the third paragraph on page two, you wrote ‘he’ when you meant ‘the. . . .’”) The replies sent back to students would go on for pages, presenting a formidable scavenger hunt.

These problems of design were not present because the staff did not care about their students. On the contrary, the tutors were extremely dedicated to helping anyone who sought advice from them. One tutor was sent a bouquet of roses after helping a student in an asynchronous session. I myself was asked into the hallway by a student, where he pointed to his name on the dean’s list and told me he would not have been there without me. The staff had strong connections with the people they worked with. But, despite their enthusiasm and commitment, the staff were determined to employ particular methods and designs that at times contradicted their work. When I took on a position at The Michigan Technological University Multiliteracies Center (MTUMC),¹ I saw a similar phenomenon in play, one where sacred cows of method and design were allowed to disrupt the counter-hegemonic efforts of the center.

Carino and Boquet have published separate broad histories of writing centers that serve to help us reflect on our current pedagogies. In response to Boquet’s suggestion that writing center history can be conceived in terms of method and space (467), I would like to offer that history itself can have a part to play, acting as a node in a feedback loop with practices and the material, because as we write history, history affects us, just as the spaces and practices we design influence our behavior. Certainly, a lack of historical awareness can blind us. When we cannot see the development of a work culture, the culture ceases to exist and instead becomes an immovable norm. Summerfield phrases the act of tracing individual center history as, “evaluating, making sense of, interpreting, criticizing. We are now spectators of our own lives, of our makings and doing” (3). Denny has also captured some history of his center, focusing on the stories of his staff in order to bring awareness to differences in class, sex, gender, and race. However, what is missing from these broad and narrow histories is an illustration of how they influence an aging and changing center.

The problematic design features and practices of my previous center had become cemented in place by history we were largely unaware of, ultimately presenting barriers to our daily work and acting as microaggressions against students who were already facing economic or social obstacles. As I continued to work at the MTUMC, I found resistance to change, no matter the improvements that change might bring. As centers age, they grow in ways we often cannot control. Centers are composed through a mutually constitutive negotiation of competing factors: the spaces we inherit, the funds we are provided, the particular needs of the institution, the vision of the center’s administrative staff, and so on. Without histories, centers are limited in their ability to improve their work. What I would like to suggest here, however, is that an active investigation that traces the histories and connections in our spaces and pedagogies can evoke awareness and break through sacrosanct practices and designs, challenging center staff to critically reflect on how their centers can transform to meet the demands of new social projects and technologies. Perhaps we can exorcise our haunted spaces and rethink how we can address histories of inequity and offer support to writers with new tools and designs.

Writing center studies frames its discourse within the bounds of a space where tutors and students meet, exploring the growth and conversations that occur within the walls of what we call centers. Centers can act as nexuses or hubs, providing a floor for activity, but they often change, either slowly or through broad redesigns, and these changes affect how tutors work with students. To make things more complicated, history lingers after a room is altered, and work cultures can develop redundant or misaligned routines that run against writing center activities, which are driven by pedagogies that may also change over time. This can make the identification of successes or shortcomings difficult, and can turn the most practical questions, like “How should we organize our workspace?” and “Who should do what, and when should they do it?” into challenges that are hard to address. My intention here is to offer an abbreviated history of the MTUMC to illustrate how tracing connections between history, material spaces, and practice can expose paths to improvement.

Over the decades, the many writing centers of Michigan Technological University have morphed into new identities with new locations and practices. These identities, practices, and locations have all responded to each other to compose an environment for literacy support. Spaces often play a crucial role in the way we interact and accomplish our communication goals (Vandenberg et al. 173). As Gresham states, “Both intuitively and intentionally, we know that spaces shape what happens in a student text” (39). Perhaps, then, a key component of writing center work is understanding our relationships with our material centers. How did the center you work in come to be and how has it grown? What is the center’s mission, and how can the physical space support your current intentions? Through an exploration of history and design, material objects and physical space can intersect with pedagogy to assist a center’s goals. Here, I will trace these intersections throughout an abbreviated history of MTU writing centers in an effort to argue for flexible writing center designs that may enhance the effectiveness of our time with writers and encourage resiliency, resourcefulness, and creativity in center staff.

A Short History of the MTU Writing Centers

While cleaning out the cluttered closet of the MTUMC, I recently discovered a heavy plastic tub of old tutoring handbooks, written materials, and photographs. I am a relative newcomer to the center, so I looked on this find as something that could help me understand the space I strove to improve. Through conferences with Sylvia Matthews, a previous assistant director and staff tutor of the center, I was able to work from these documents to assemble a short history of MTU writing centers and maps of three of these centers. Diana George, the MTU Director of Tutor Education from 1978-1983, was also able to provide details of the MTU Writing Center’s early variations.

The earliest version of the MTUMC was the MTU Language Skills Lab of the 1970s, which operated as an auto-tutorial remedial English course (George). Diana George describes the lab as “an odd conglomeration that was antithetical to anything I would ever call a writing center.” It was directed by Richard Mason and staffed by professional tutors working ten hours a week. The program was housed in a computer lab where students who were assigned the course or sent to the lab by an instructor would study independently to teach themselves correct English grammar. There, the staff worked to “solve a number of language-related problems,” according to the employee handbook of the time (Freisinger 2). The lab of computers, printers, and bound resources on writing hosted three courses that functioned as weekly appointments, each worth one course credit: HU011, for students with low ACT scores in need of “remedial work;” HU022, for all other students who needed help with writing; and HU021, for students interested in improving their reading skills (3-5). Weekly appointments were required to spend two hours a week composing in the lab (per every one credit hour they registered for) in the presence of a tutor, and tutors were expected to plan assignments for their students to help them improve (1).

Nancy Grimm recalls this center, where she worked as one of the tutors, as running “skill-and-drill remediation lessons,” which were followed by individualized instruction (“New Conceptual Frameworks” 12). She also recalls the room was filled with carrels (a sort of cubicle combined with a table) and shelves of workbooks, tapes, and audio equipment. Diana George remembers students would work from audio cassettes to fill in the blanks in their workbooks. There was no staff training, and tutor roles were undefined. When students would finish with their books, they would bring their work to the lab coordinator, who would often sit with his feet up on the front desk, flip through the completed book, and toss it aside in full view of the student. As George describes the lab’s activity, “It was pretty bleak.” Some staff members were ill-equipped to tutor reading and writing because of the lack of training. Others failed to appreciate the social, institutional, or economic inequalities that brought students to the lab’s door.

In 1978, Diana George was tasked with developing training for Language Skills Lab tutors. Although Richard Mason strongly defended the lab in its current state, he was largely uninvolved with running it. This allowed George enough agency to eventually reshape the center from the inside out, ignoring the auto-tutoring elements she had inherited. It would be years until the Language Skills Lab would change its name, but material and pedagogical shifts began. George says, “I made two really important decisions in terms of training tutors.” First,

Tutors had to meet as a group every week, and that hour would be paid. . . . I had been heavily influenced in grad school by the work of people like Ken Macrorie, Ken Bruffee, and others who were talking about new ways of thinking about teaching writing. I wanted my tutors to know that stuff and to work with students and papers they brought to the Center; not on workbooks or anything close to that.

Second, George said,

I demanded a separate space for tutoring, and that space was simply an empty classroom with five tables. I didn’t want equipment or barriers. I just wanted tables and chairs where tutoring could happen. I wanted students to see other students being tutored and to know there was no shame or punishment in that.

Thus, the Language Skills Lab began to operate out of one classroom intended for thirty students that had been partitioned off into two separate areas. There was no front desk where a coordinator could apathetically prop their feet, but while students met in half of the classroom, the other half beyond the partition had been transformed into the director of tutor education’s office and a meeting room. The meeting room became a place for tutors to relax, talk about sessions, and share food, allowing for more professional activities in the lab. To George, this was when the Lab became a writing center. As she says,

The regular meetings talking about composition theory and pedagogy, that became the basis for what I think of as a writing center...That’s when we began presenting at conferences and, eventually, publishing in the field.

She says she wanted to make the center as student-oriented and current in writing pedagogy as possible. All further variations of MTU writing centers would continue with these core changes as they developed.

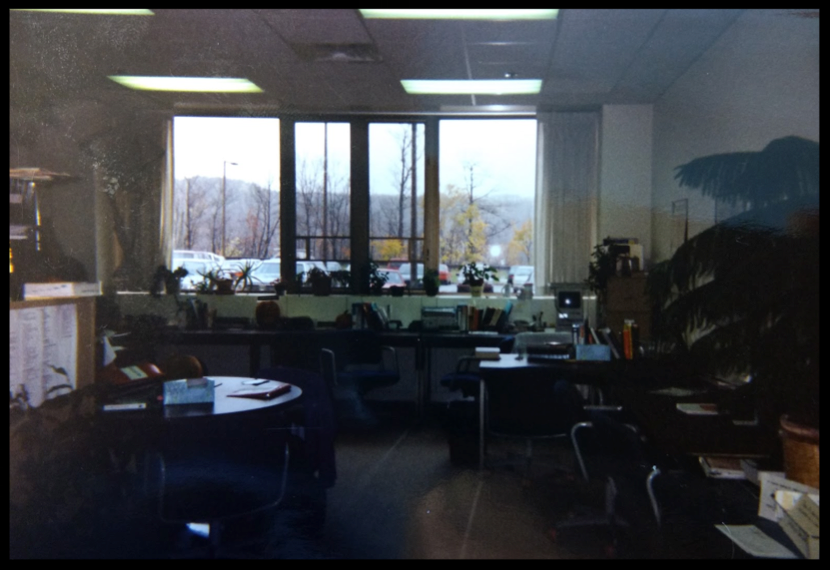

In 1989, Nancy Grimm coordinated a new program titled “The Reading/Writing Center” (RWC). The tutors were moved into a boxy single room within the Humanities Department where they could observe the sprawling wilderness across Portage Lake through a long line of wide windows (see Figure 3 in Appendix). The handbook of that year states the RWC’s goal was to make “the student writer’s world a bit more perfect.” In this center, weekly appointments and credit courses were still the norm, and tutors were expected to report “teaching notes” back to instructors, which would assess the “strengths and weaknesses” of each student (Grimm, “Reading/Writing Center Tutor Handbook” 19). Tutors were instructed to always sit next to students at small rectangular tables, but the rolling chairs had arms that would never fit underneath the table surface, forcing the tutor and writer to distance themselves from the student’s writing (Matthews). Though unintentional, this element of the room’s design worked against the postmodern philosophy the center would later adopt.

In 1992, the RWC program ended, and the first peer tutoring program at MTU began, directed by Nancy Grimm and named The MTU Writing Center. This version of the center thrived for several years and resembled in many respects what we would currently consider a typical writing center. Tutors became “coaches.” Students collaborated with other students to learn about writing. Photographs of the time show a cluttered but intimate center, where a small staff forged strong connections with students (Figures 4-7 in Appendix). False walls of filing cabinets and shelves were erected to carve out an office for a secretary near the entrance (Matthews). On the false wall closest to the entrance, an enormous bulletin board displayed the weekly appointment schedule.

The 1993 MTU Writing Center handbook envisioned the program as a support service “beyond the realm of the classroom” where “students can turn to when institutional expectations are confusing or challenging” (Grimm et al., The MTU Writing Center Handbook 3). Both graduate and undergraduate students were employed and served. However, legacies of practice haunted this new site, as they continue to haunt the current center. The Language Skills Lab functioned as an extension of a classroom, offering courses for students that had been identified by the institution as in need of remediation. To help tutors mend their student’s inadequacies, an hour of preparation time was provided to them each week (Grimm et al., The MTU Writing Center Handbook 7th ed. 8-9). In the MTU Writing Center, this tradition continued for all coaches. Although emphasis was placed on collaboration in learning, coaches were expected to somehow prepare and plan for sessions. The assumption was that coaches should know something more than writers and administer the appropriate information. In addition, even though tutors were no longer designing course assignments for their students, writers were still enrolled in writing center courses that would appear on their official transcripts. The courses would be graded in a satisfactory/unsatisfactory binary, based on attendance. The enrollment was justified as a way to help promote the visibility of the center’s work, while the grades were seen as a way to hold students accountable. At some point, these courses would also be used to track student success throughout the college experience, but they would also unfortunately forever mark students who sought help.

This new writing center identity was eventually followed by a comprehensive remodel of the physical center space in 2007. The solid hallway wall was replaced with stainless steel framed windows. The wall of the classroom next door was knocked down to create a conference room and offices. The wall on the opposing side was likewise demolished to create a break room and two more conference rooms (Matthews). The result was an open center surrounded by side rooms for noisy groups. A back hallway slithered behind all of this, leading to the break room, where coaches could hang their coats and enter the center. The session tables were also round—a feature also identified as helpful by Berry and Dietrle (28)—to assist coaches and students sitting at the proper angle to view the same document. The tables also had a dark natural wood finish to provide an atmosphere of established equanimity. The chairs, colorful and wheeled, did not have armrests so they could be pushed under the tables. The administrative desks featured rounded peninsulas to accommodate side conferences with coaches and writers. Figure 2 (see Appendix) is a map that was created at the time. The arrows are meant to illustrate constant activity in a complex new space. This map is described in the recovered document as “a map of our interactions” where students and coaches “are all connected by our diverse, dynamic, and worthwhile experiences” (“Welcome to the Michigan Tech Writing Center” 1). The 2009 tutor handbook reflected this new environment. “Our job as writing center coaches,” the introduction reads,

is to work with people and figure out what’s expected in new situations. . . . You’ll find that your job in the Writing Center. . . involves struggling with complex issues, questioning commonplace assumptions, and regularly monitoring your interpersonal skills and self-awareness. (Grimm et al., Michigan Tech Writing Center Handbook 2)

The 2007 map and 2009 handbook engage issues that Nancy Grimm had been writing about for some time, and the alterations to physical space reflected the development of her pedagogy. In her 1995 dissertation, Grimm wrote,

A postmodern writing center practice shifts the writing center function from one of upholding standards to one of understanding the systems of relations by which our words become intelligible. Writing centers were initially established to maintain standards. . . now they can be places that raise questions about how standards function and whose interests they protect. (Making Writing Centers Work 274)

By 1999, these ideas had solidified into a book aiming to conceptualize a new type of postmodern writing center that disregarded the problems of modernity. Grimm writes,

In the writing center, an emphasis on relationship rather than individualized instruction allows me to leave behind defensive concerns about how much help is too much and whether the tutor is adequately enacting the teacher’s desires. Instead I can keep the focus on the ways the writing center supports students’ efforts to enter into relationship with academic values, disciplinary texts, mainstream literacy. I can remember that literacy is the achievement of a relationship with other minds, with a culture’s texts, and with a discipline. (Good Intentions 18-19)

Later, Grimm would cite the New London Group book, Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures (originally published in 2000), as a major influence on the center’s pedagogy (Balester et al.). This strengthening in direction ultimately led to a distinct new identity for the center.

In 2010, The MTU Writing Center became the MTUMC in order to

recognize the range of negotiating activity required for learning and communicating; [the name] replaces the notion of “norm” with the recognition that different situations call for different kinds of literacies. (Grimm and Arko 9).

The physical and aesthetic design of the center endeavored to support this framework. At this time, wicker baskets arrived in the center to hold office supplies, suggesting the interlaced relations in our work. Donated cultural artifacts from all over the world rested on every surface. Dolls in traditional Chinese robes. A painting of a Hindu religious figure. Native American pottery. Terracotta figurines. Most notably, however, was the addition of the 37-inch-wide Geochron clock, which was acquired at considerable expense and mounted by carving a hole into the wall. The clock swiftly broke, and despite being repaired once, has not moved in several years. This highlights a key feature of this version of the MTUMC: a de-emphasis of the role of technology in writing center work. Despite technological advances, the center persisted in the use of physical paper records stuffed into filing cabinets placed in offices, the closet, the break room, and even the open space. Every coach’s prep time turned into data management time, in order to provide a place on the schedule to complete paperwork. Attendance data was divided and kept in separate locations, and there was no active shared document drive on the campus network. Assembling the annual report was a huge undertaking that persisted throughout the summer. The computers in the center were pushed to the edges of the room to optimize them for individual work, but not collaborative use in sessions. The computers also only provided students with basic spreadsheet and word processing software, so they were not ideal for composing multimodal texts or developing visual designs.

Nancy Grimm retired from MTU in 2012, and with her left decades of MTU writing center history. This historical vacuum created a work culture where the staff continued to do things with little thought to purpose. Karla Kitalong directed the center for a year, providing mentorship as Abraham Romney prepared for the position. In 2014, Abraham Romney was appointed to be the new director, and the MTUMC began to shift into a new identity, one that included technological literacy into the larger framework of multiliteracies. As Bancroft explains,

Digital literacy functions in a system of power of those who have versus those who have not. . . . Multiliteracy centers must be aware that digital literacy can be key to students’ success and provide access to the resources students need to succeed in their 21st-century communication tasks. (51)

In this new center, paper files were immediately done away with and replaced with Accudemia, an electronic web-based attendance tracker and scheduler, which also eliminated the need for prep time. (This realization about prep time dawned on us sometime later). New desktop computers were purchased. A sign-in station with a tap card reader was installed at the front desk. A flat screen television was acquired to display slides through the wall of glass. Laptops were procured for use in sessions. In 2016, we renamed one of our conference rooms “The Writing Studio” and installed a digital design station within it. The station features a computer with the complete Adobe suite (supporting visual and aural composition), monitor headphones and speakers, dual monitors, a recording interface, and three microphones.

Changes in the work environment occurred rapidly, and many coaches did not quite know how to react. Even a year and a half after the web-based system was implemented, several coaches continued to secretly keep paper files on their appointments, slipping them into unused file cabinet drawers. Most coaches also expressed anxiety at using the new technology. They didn’t know how to use Photoshop or Premiere, and were uncomfortable with the idea of a session involving such software. The coaches were very comfortable working within other literacies, but using unknown technology seemed to stop these normally resilient minds in their tracks.

Growing centers need to critically reflect on not only their session pedagogies, but also their material traditions and managerial practices. During the MTUMC’s latest transitional period, a graduate student was shocked to find me working with a few of our more creative coaches to paint a mural on the wall in the Writing Studio. She was quick to criticize my judgment, even after I told her it was washable paint, and in a place where we could just hang a bulletin board over it if we didn’t like it. As the 2012 MTUMC handbook states “writing centers are ‘haunted’ sites” (Grimm and Arko 150). True, they are haunted by legacies of systemic inequalities, but they can also be haunted by legacies of centers past, and it is up to us to ferret out the ghosts in our work.

The anxiety and unrest of the staff remained until we began assembling the history of the MTUMC and understanding how certain features and practices came to be. Why were we organizing study teams for anthropology classes? Why were we enrolling weekly appointments into classes when we could track them with more detail a different way? Why didn’t that huge world clock ever move? With history came the perspective necessary to move the center into new territory. We were able to identify what the MTUMC was and what it did, and use that knowledge to expand and improve. We realized we needed patient, resilient, careful thinkers, not experts in writing, audio, or visual design. We offered training sessions in a computer lab where our staff could work with new software. We walked the coaches briefly through a few basics in Photoshop and Audition and then left them free to explore on a low-stakes creative project. We began to encourage coaches to use our design station to create promotional videos and images for the center. The trick was to give them a little orientation and then let them explore and create. Instead of dictating exactly what a coach should know or assuming what was going to be useful in a session, our aim was to help coaches develop the ability to approach unfamiliar texts in multiple modes and problem solve. For these projects, administrative staff assumed the role of the non-directive coach, providing feedback, offering technology support, and modeling problem-solving behavior.

Defining a Space

Writing centers can certainly be relaxed spaces of open conversation, exploration, and collaboration, but center staff often have trouble articulating exactly what their work entails. When it comes to planning the physical space of a center, James Inman advises, “Design begins with an evaluation of what clients will actually be doing” (22). Can we say we “help” students? Don’t writing center sessions often concern things other than written text? Are sessions really a form of tutoring? Staff will have to navigate these questions to find a satisfactory description of writing center work in order to consider how center design can support session activity.

In the current Multiliteracies Center, the activity of the staff is just as important as the activity in sessions. Coaches are actively encouraged to work together in order to gain experience with unfamiliar technologies and composing in multiple modes. Driven by a philosophy of continual improvement through collaboration and revision, outreach materials such as workshops, graphics, blog posts, and videos are developed, refined, and deployed. Our process is similar to the refactoring strategy proposed by Benjamin Lauren, which “suggests internal processes and procedures can be improved incrementally as stakeholders interact with the system” (72). Refactoring, Lauren explains, is “used by software programmers to work with legacy, or inherited, code, which speaks broadly to the historical institutional context many centers work within” (72). This approach allows our staff to become more skilled in working with others on unfamiliar terrain.

In sessions, coaches interact with writers from all over campus and the world. We work to make them feel welcome so that we might learn from each other. As Joseph Bianco describes multiliteracies:

The Multiliteracies Project aims to develop a pluralistic education response to trends in the economic, civic and personal spheres of life which impact on meaning-making and therefore on literacy. These changes call for a new foundational literacy which imparts the ability to understand multiple modes in which those codes are transmitted and put to use; and the capacity to understand and generate the richer and more elaborate meanings they convey. (92)

From this viewpoint, coaching becomes a process of discovery, where the coach not only learns with the student, but from the student’s life experiences, using them to construct meaning in each session. Coach training, then, moves away from building specialized writing expertise and toward developing resiliency, patience, and problem-solving skills. This principle guides us through weekly, one-time, and walk-in appointments, as well as our graduate writing groups, synchronous and asynchronous online appointments, conversation circles, workshops, and study teams.

The center reserves space in The Writing Studio and along the open space’s back wall for students to work individually. Composition instructors often assign multimodal projects that incorporate text, audio, and visuals, and so our equipment has grown useful to students who need to compose these texts. Graduate students and researchers are also common in the center. Sometimes they require help with designing presentation posters, other times formatting dissertations. MTUMC sessions, above all else, aim to promote literacy access, cognitive modeling, transliteracy, and cultural understanding.

Hybrids in the Center

The task of optimizing a center’s design is also a challenge to understand the social, technological, and natural elements of the institutions and populations that centers serve. When I first arrived at the MTUMC, there was a tendency for the staff to think of the material center as a stable identity, and there was little sense of the relationship we had with our material space, even as some of the cultural artifacts became sun-faded and the room became increasingly cluttered and disorganized. Bruno Latour wants us to think about our relationship with our physical surroundings as a composite of multiform actants who must work to compose a common world (4). Essentially, he asserts that our environment is not a stable place to be maintained, but an inconceivably complex network of human and nonhuman influences that together create a habitat. Designing a center, then, is not as simple as deciding what the administrative staff would like to do. It involves negotiating the material and the work culture that has grown around it to produce what Thomas Rickert would refer to as ambient rhetoric, a design intended to persuade both staff and writers toward a particular perspective or writing behavior (206). If we want to stress collaboration in learning about writing, shouldn’t all computers in the center have two mouses and two keyboards? If we want to stress inclusivity and access, shouldn’t we play soft music from a diverse range of cultures in the background? How would the center staff or institution react to such changes? How could these new features be misused?

Examining space and activity is a complicated endeavor that incorporates design, hybridity, rhetoric, and tracing networks of actors throughout history. Don Norman stresses that design should take into account the perceived affordances of the landscape. As Norman explains, “Affordances are the possible interactions between people and the environment” (19). Norman also contends that the discoverability and strategic location (what he calls mapping) of objects also play a huge role in how tasks are completed (2, 113).

Center design should attempt to accommodate Jonathan Mauk’s description of third space, a place “where academic space is dispersed throughout students’ daily lives, a dimension emergent from the generative collision of academic, domestic, and work spatialities” (214). It should reach to act as a space where writers can recognize composition in their homes and workplaces. Many centers strive to accomplish this through dressing their centers as homes or offices. Natalie Singh-Corcoran and Amin Emika describe typical writing center decor as “comfortable, inviting, friendly, non-threatening, non-institutional, relaxed, informal, and attractive.” The intention is to often use coffee pots, couches, houseplants, and art to mark the space as on the fringes of the academic world, thereby merging academic work with the realities elsewhere. These material choices encourage us to interact with our physical surroundings as we take on mental composing tasks.

One of the first material changes I made to the MTUMC when I started was to place office supply organizers at each session table. True, the organizers lent a distant business/professional air to our coaches, but they also held recycled scrap paper for notes, pencils, and bookmarks with our hours, services, and web address. It did not take long for coaches and writers to begin using these organically in their sessions. If the student forgot a pencil, they would find one right in front of them; coaches would snag pieces of scrap paper to explain writing concepts without drawing all over a draft; and when time in the session ran out, students could grab a bookmark for information on how to schedule another appointment. This was just logical mapping. Landon Berry and Brandy Dieterle write of interstitial and surrounding space in multiliteracy center sessions. In the sessions they observed, interstitial space primarily concerned material objects. A pencil and scrap paper, positioned into the right space, could act as a conduit between two minds. Common material objects that a session would require were on hand at the table. The writer, coach, and environment were able to converge and compose. When students or coaches bring their smartphones, tablets, or laptops into the session, interstitial space is widened across the world, providing access to knowledge, communication tools, or an online appointment scheduler (25-28). Each table can come to operate as a miniature writing center, fractal representations of the whole capable of responding to the chaos of writing center work.

Margaret Heffernan asserts that success in any work relies on the helpfulness of the workers. “And what drives helpfulness,” she explains, “is people getting to know each other.” The key to this strategy is to promote empathy, equality, and diversity, while also scheduling time for workers of diverse expertise to socialize. One way she suggests to accomplish this is through scheduled employee coffee breaks, where staff members from different project teams can congregate around a coffee machine, socialize, and learn from each other. Heffernan claims that this organization “routinely outperforms individual intelligence” in every company she has started or worked for. Successful career professionals, she remarks, are the successful collaborators who found the best in themselves by finding the best in others. Laszo Bock supports similar claims about emphasizing diversity and social networks over promoting individual achievement (“How Google’s”), but he also insists that everything must begin with a shared goal, what he calls giving work “meaning” (Bock, Work Rules 348). This suggests that making social objects more central to a center’s activity could facilitate composition, if the goals of the center’s work could also be materially represented. However, these material rhetorical moves will still need to negotiate with history and practices. An awareness of history can expose material and methodological connections and allow critical reflection.

In the 2017 MTUMC, the material representation of our values and goals comes in the form of the international cultural artifacts displayed throughout the center, as well as the world map mural. The artifacts have been donated throughout our history by past coaches. The mural was my addition, one that caused some controversy. For other centers, their goals might be represented in catchy phrases on posters, slideshows on screens, or quotes painted on walls. Social objects such as hospitality bowls, handout displays, coffee machines, teakettles, or popcorn machines can also be positioned into an easily discoverable location where students and coaches might find opportunities to interact. Social objects, however, can be anything that attracts people. Music or art. Games like Table Topics, Storymatic, Rememory, or Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes. One center that seems to have taken advantage of a social object in their work is the Grand Valley State University Knowledge Market, which consists of a kiosk in the university library’s busy lobby (“Knowledge Market”). Piggybacking off the attraction of the newly built and very stylish library as a study and research hub, the Knowledge Market is simply a place where students can bump into a consultant and ask for help.

Laying It All Out

When I first arrived in the MTUMC, I was not aware of the complete history of MTU writing centers, and I was ill-equipped to negotiate with the disturbance my refactoring efforts inflicted on the staff’s work culture. I could not move so much as a bookcase a few feet without upsetting the staff. Even removing empty, unnecessary filing cabinets from the break room raised some eyebrows. After each adjustment, I would watch the room to see how writers and coaches used the space. Eventually, we arrived at our present configuration, which seems to function well (See Figure 1 in Appendix). Norman advocates for constraints in design, which limit possible outcomes (82). For this reason, we have positioned a walk-in coach at a rectangular table, which visually blocks off the rest of the room while maintaining a sense of openness. The walk-in coach acts as a guide for those who enter. If they are here for an appointment, they are directed to turn to their left and sign in. If they cannot be seen immediately, they are directed to turn right and sit in a chair. If they are here to work independently, they are pointed to the Writing Studio to their right.

Some students only briefly duck their heads in after spying our bowl of mints at the sign-in station desk. (Sometimes, when the center is closing and the lights are off, students dart in to steal a mint). Positioned next to this bowl is our handout display, in case they need any materials. In the 2007 version of the center, the handouts were kept in a filing cabinet at the back of the room. The intent was that if students wanted a handout, they would have to make an appointment. Because the Internet is so accessible now, and contains so much information (accurate or otherwise), it would be better for a student to snag one of our handouts and make an appointment later if they need any of the information on it explained. The key to this strategy, of course, is to have our logo and contact information at the top of each document. Again, this engages with Heffernan’s point about creating a culture of helpfulness. The challenge isn’t always getting students to sign up for an appointment. Sometimes it is getting them to realize what we have to offer.

Writing centers are by necessity chaotic places of dissent and collaboration, of directiveness and non-directiveness, of encouragement and crisis counseling, of independent expression and learning to conform to institutional standards. Centers need to be capable of responding to this chaos. In the 2017 MTUMC, function flexibility is a key design feature. The open space tables have been scattered randomly to purposely avoid the neat order of a classroom (this is a distinct departure from the 2007 and 2000 center maps, as can be seen in Figures 2 and 3 in the Appendix), and the center now has laptops for session use. When I first arrived, as is indicated in the 2007 map, the session computers were crammed into the far corner of the room, on a circular table that was not nearly big enough to accommodate two computers and coaching sessions. So, we removed two rectangular tables from what is now The Writing Studio (which at that time was just being used as another meeting room) and set the computers on those so students and coaches can now work side-by-side and have equal access to viewing the screen, or work independently at separate computers. The spare circular table was added to the center of the open space, which then became too cluttered. We then decided to develop The Writing Studio, and set two round tables in there for individual work, along with a new computer station for digital design. The Writing Studio also served a second vital function. Because we had set up session tables in a smaller room with a door, we could now afford to use the open space for large workshops and presentations while also holding one-on-one sessions.

When the side rooms were added to the center in 2007, they were used for study teams and group work. However, as was mentioned before, each table in a center can operate as a miniature version of the larger center without any conversion time. If relevant tools are organized and discoverable at each table, and enough center resources are digitally available online, certain areas of the center can be optimized for certain appointment types, while every space can be made to support the most common types of appointments. This allows center activity to be diverse and actors to connect seamlessly. For the 2017 MTUMC, this meant that we no longer had to closely monitor the number of students who signed up for study teams or attended our workshops.

Design flexibility, however, depends on a culture that is willing to engage with it. If a center’s furniture configurations were flexible, if every table, chair, and resource was mobile, the center could reshape itself to respond to every situation. Amanda Bemer et al. suggest, “giving students the ability to create and adapt their technological spaces will help them work in collaborative ways” (152). If coaches, tables, and chairs become wheeled, and laptops are made available in place of desktop computers, a center can easily be composed by the network, facilitating collaboration and understanding. Bemer et al. tried just this for classroom use, composing a room of wheeled couches and tables, but what they found was that, even though everything was on wheels, students would not move any of the furniture for group work. Likely, this is because students have been conditioned to comply to traditional classroom decorum, which requires students to refrain from disruption, and students lack sufficient moral development to know when to act against this social script. This mentality is not ideal for collaborative and creative activities; ultimately, the authors advised that collaborative writing spaces with wheeled furniture display posters to make it clear that users are allowed to manipulate the position of objects and offer possible configurations for different activities (Bemer et al. 161). This material adjustment pushes back against classroom culture and encourages students to enact better methods of collaboration, which in turn can drive them to engage in moral development where they take into account “the perspective of every person or group that could potentially be affected by [a] decision” (Sanders), a philosophy that reaches for Latour’s theory of how we interact with the world.

In the 2017 MTUMC, the chairs are wheeled, and I am constantly bringing them back to their proper place as I walk through the room. Sometimes all the chairs from one table will form a crowd with the chairs at another. Sometimes chairs intended for the session tables will rest at the grad student desk, possibly seeking guidance. Sometimes the heavy round tables are pushed away so the chairs can form an unbroken circle of support. This is a material representation of the chaos of the center. Our work is messy and unpredictable. The freedom with which the furniture now moves marks this place as the opposite of a classroom, a postmodern center, but it only exists because together the center staff has worked to shift its work culture, which grew from a history we had to make ourselves aware of. My hope is that other centers might learn from our experience and consider deploying similar strategies to question and reflect on how their work can accommodate new technological realities and pursue social projects. Centers need to see themselves as always in motion, and they need to be capable of always responding to the emerging context shaping our material and cultural realities.

Notes

We normally call our center “The MTMC” (Michigan Tech Multiliteracies Center), but for the sake of clarity, the full acronym is used throughout.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Karla Kitalong, Diana George, and Sylvia Matthews for their assistance in my research of the early years of the Michigan Technological University Writing Centers.

Works Cited

Balester, Valerie et al. “The Idea of a Multiliteracy Center: Six Responses.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 9, no. 2, 2012. www.praxisuwc.com/baletser-et-al-92/. Accessed 26 June 2018.

Bancroft, Joy. “Multiliteracy Centers Spanning the Digital Divide: Providing a Full Spectrum of Support.” Computers and Composition, vol. 41, 2016, pp. 46-55.

Bemer, Amanda et al. “Designing Collaborative Learning Spaces: Where Material Culture Meets Mobile Writing Processes. Programmatic Perspectives, vol. 1, no. 2, 2009, pp. 139-166.

Berry, Landon & Brandy Dieterle. “Group Consultation: Developing Dedicated, Technological Spaces for Collaborative Writing and Learning.” Computers and Composition, vol. 41, 2016, pp. 18-31.

Bianco, Joseph. “Multiliteracies and Multilingualism.” Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures, edited by Cope, Bill and Mary Kalantzis, Routledge, 2000, pp. 89-102.

Bock, Laszlo, et al. “How Google’s Laszlo Bock is Making Work Better.” Hidden Brain. National Public Radio. Interviewed by Vedantam, Shankar. 7 July 2016. Transcript. www.npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyId=480976042. Accessed 27 June 2018.

Bock, Laszlo. Work Rules: Insights from Inside Google that Will Transform How You Live and Lead. Hachette Book Group, 2015.

Boquet, Elizabeth. “‘Our Little Secret:’ A History of Writing Centers, Pre-to Post-Open Admissions.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 50, no. 3, 1999, pp. 463-482.

Carino, Peter. “Writing Centers: Toward a History.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 15, no. 2, 1995, pp. 103-115.

Denny, Harry. Facing the Center. Utah State UP, 2010.

Freisinger, Diana. The Tutor’s Handbook. Collection of Department of Humanities, Michigan Technological U, Houghton.

George, Diana. Personal interview, 5 July 2017.

Gresham, Morgan. “Composing Multiple Spaces: Clemson’s Class of ‘41 Online Studio.” Multiliteracy Centers: Writing Center Work, New Media, and Multimodal Rhetoric, edited by Sheridan, David and James Inman, Hampton Press, 2010, pp. 33-55.

Grimm, Nancy and Kirsti Arko. Michigan Tech Multiliteracies Center Handbook (14th edition). 2012. Collection of Department of Humanities, Michigan Technological U, Houghton.

Grimm, Nancy et al. Michigan Tech Writing Center Handbook (11th ed.). 2009. Collection of Department of Humanities, Michigan Technological U, Houghton.

Grimm, Nancy et al. The MTU Writing Center Handbook (7th ed.). 1993. Collection of Department of Humanities, Michigan Technological U, Houghton.

Grimm, Nancy. “New Conceptual Frameworks for Writing Center Work.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 29, no. 2, 2009, pp. 11-27.

Grimm, Nancy. Good Intentions: Writing Center Work for Postmodern Times. Heinemann, 1999.

Grimm, Nancy. Making Writing Centers Work: Literacy, Institutional Change, and Student Agency. 1995. Michigan Technological U, PhD dissertation.

Grimm, Nancy. Reading/Writing Center Tutor Handbook (3rd ed.). 1989. Collection of Department of Humanities, Michigan Technological U, Houghton.

Heffernan, Margaret. “Forget the Pecking Order at Work.” TED, 2015. www.ted.com/talks/margaret_heffernan_why_it_s_time_to_forget_the_pecking_order_at_work. Accessed 26 June 2018.

Inman, James. “Designing Multiliteracy Centers: A Zoning Approach” Multiliteracy Centers: Writing Center Work, New Media, and Multimodal Rhetoric, edited by Sheridan, David and James Inman, Hampton Press, 2010, pp. 19-32.

“Knowledge Market.” Grand Valley State University, 6 Aug. 2017. www.gvsu.edu/library/km/index.htm?contentid=840CDA21-0D50-1730-F4B3C1B66CB0A984. Accessed 26 June 2018.

Latour, Bruno. “Some Advantages of the Notion of ‘Critical Zone’ for Geopolitics.” Procedia Earth and Planetary Science, vol. 10, 2014, pp. 3-6.

Lauren, Benjamin. “Running Lean: Refactoring and the Multiliteracy Center.” Computers and Composition, vol. 41, 2016, pp. 68-77.

Matthews, Sylvia. Personal interview. 13 April 2017.

Mauk, Johnathon. “Location, Location, Location: The ‘Real’ (E)states of Being, Writing, and Thinking in Composition.” Relations, Locations, Positions, edited by Vandenberg, Peter et al., National Council of Teachers of English, 2006, pp. 198-223.

Norman, Don. The Design of Everyday Things. Basic Books, 2013.

Rickert, Thomas. Ambient Rhetoric. U of Pittsburgh P, 2013.

Sanders, Cheryl. "Lawrence Kohlberg’s stages of moral development." Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 Jul. 2016. academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Lawrence-Kohlbergs-stages-of-moral-development/627328. Accessed 26 Oct. 2017.

Singh-Corcoran, Nathalie and Emika, Amin. “Inhabiting the Writing Center: A Critical Review.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 16, no. 3, 2011. http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/16.3/reviews/singh-corcoran_emika/physical-space.html. Accessed 26 June 2018.

Summerfield, Judith. “Writing Centers: A Long View.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 8, no. 2, 1988, pp. 3-9.

Vandenberg et al. Relations, Locations, Positions. National Council of Teachers of English, 2006.

Welcome to the Michigan Tech Writing Center. 2007. Collection of Department of Humanities, Michigan Technological U, Houghton.

Appendix

Figure 1: The MTU Multiliteracies Center - 2017

Figure 2: The MTU Multiliteracies Center - 2007

Figure 3: The MTU Multiliteracies Center - 1989-2006

Figures 4-7: Photos of the 1989-2006 MTU Writing Center

The schedule board also served as a false wall.

The center’s windows provided a view of the Keweenaw wilderness.

A coach and a student work with a draft.

Dr. Glenda Gill (center) and Dr. Nancy Barron (left) attend the annual African American Read-In at the center.