Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 17, No. 1 (2019)

Writing Groups: An Analysis of Participants’ Expectations and Activities

Claire McMurray

University of Kansas

mcmurrayclaire@ku.edu

Abstract

Writing groups are a valuable way for writers to improve their writing, receive feedback, gain accountability, and increase their motivation. However, groups are only beneficial if participants decide to join one, stay in it, and are satisfied with the outcome. Much of what guides these decisions is based on what participants initially expect from a group. Little is known about what potential writing group members believe they will do in a group. The current study offers data about writing group expectations and satisfaction rates gathered from surveys and interviews with writing group participants. Findings suggest that expected writing group activities fell into four separate categories: skill-based, draft-based, time-based, and emotion-based activities. Recommendations for writing groups are offered based on these trends.

INTRODUCTION

“Due to my poor English grammar influencing my course paper, I think I need to join a writing group to improve my writing ability.”

“I think I could benefit from some accountability.”

“I’m interested in […] getting some serious writing done.”

“I want to take the writing lessons, look forward your help and tell what I should to do.”

“Is this group like a student organization or it is tutoring?”

The quotes above are taken from emails sent to me by graduate students and visiting scholars interested in joining a writing group in our writing center. Their words highlight how widely motivations to participate in a group can vary, how participants may hold misconceptions about groups, and how writers may not understand what a writing group is at all. At our writing center, such inquiries are par for the course at the beginning of every semester. The students’ and scholars’ common questions and hopes regarding writing groups have led me, as the coordinator of such groups, to ask questions of my own. What do participants really want from a writing group? What do they expect it to be like? What activities do they imagine they will do in a group? I ask these questions because participant expectations can often affect a writing group’s functioning, attendance record, and success. I have found that expectations guide whether a participant decides to join a certain group, continues to participate in it, and is ultimately satisfied with the experience.

These common questions led me to investigate what participants expected from writing groups in my writing center. Over the course of several semesters I administered a series of participant surveys and conducted interviews that probed expected writing group activities. In general, expectations fell into four main categories: skill-based, draft-based, time-based, and emotion-based activities. Each category grouped together similar types of activities that happen in writing groups, such as “working on my thesis or dissertation,” “jumpstarting my writing,” or “becoming motivated about my writing.” I also looked at what actual activities these participants engaged in during the semester and how this affected overall satisfaction rates. I then created recommendations about forming and running writing groups based on these findings. I found that it is important to explain what a writing group is and how it functions to novice group members before they meet. It is also extremely helpful either to create separate groups based on my four activity categories or to conduct one’s own investigation of expected writing group activities in one’s local context. Lastly, all writing group members must understand the importance of bringing specific documents to work on in their group.

In this article, I briefly sketch out the literature on writing groups and my study’s theoretical framework in Part I before I explain how my study was designed and carried out in Part II. In Part III I present and discuss my findings before summarizing major trends in the data and offering recommendations in Part IV. In the end, I discuss the by discussing limitations of my study and providing some final thoughts about writing groups.

PART I: THE LITERATURE ON WRITING GROUPS

Defining and Dividing Writing Groups

Writing groups can be difficult to define and discuss because they vary so widely. Sarah Haas points out that there is no “fixed understanding” of groups, though all “involve writers coming together to support each other” and “share the common goal of improving both process and product of writing” (31). Several types of writing groups also exist, such as groups that use the time to write, groups that primarily provide emotional support, and groups in which drafts are exchanged. The diversity of writing groups means that they can be divided and analyzed from several different angles. Scholars have written about groups inside and outside the classroom (Moss et al.), undergraduate (George; Spear; Graham et al.) and graduate groups (Gradin et al.; Maher et al.; Aitchison, “Learning”), groups with and without leaders (George), and groups internal and external to universities (Aitchison, “Writing”). A few authors have also demonstrated how particular groups can also focus on certain populations, such as women, dissertation writers, faculty members, and community members (Inman and Silverstein; Pololi et al.; Westbrook; Fajt et al.).

For the current study, I have chosen to focus on the reasons why participants join a group. A few scholars have briefly mentioned how groups can be divided upon these lines. In Haas’ “Pick ‘n Mix Typology,” made up of 11 different writing group dimensions, she describes three different “purposes” for a writing group: generally provide mutual support to increase quantity/quality of writing of members, specific activity common to members, and other purpose (32). Maher et al. also discuss different “motivations to participate” in a writing group: protected time and space, maintaining momentum, accountability to others, and common purpose (199-202). However, there are many more motivations one might have for joining a group, as my research on writing group participants’ expectations will demonstrate.

Writing about Groups

There is a strong consensus in the literature about the positive outcomes and benefits of groups. Most of those who write about groups agree that writing groups have powerful benefits, such as sustained support from other writers (Phillips), strategies for learning to write (Aitchison, “Writing”), metacognition about the writing process (Ruggles Gere and Abbott), and active participation in the creation of knowledge (Ruggles Gere).

Though there are some theoretically-informed works about writing groups, such as Anne Ruggles Gere’s Writing Groups: History, Theory, and Implications, scholars generally approach groups through individual case studies of successful groups. These studies tend to be descriptive and reflective but contain little data, such as survey results or interviews with participants.¹ Most discussion about writing groups also focuses on what has happened after a group has begun operating successfully (Maher et al. 195). Little consideration has been given to what happens before a group begins to meet.

We know from other areas of writing center scholarship how crucial initial impressions and expectations can be. Scholars have done much work to study and combat the common misconceptions about writing center consultations: papers being edited or proofread, tutors teaching grammar lessons, consultations increasing a student’s grade, etc. (North; Farkas; Rollins). Many researchers have also considered how students and faculty perceive writing centers generally (Hayward; Rodis; Masiello and Hayward; Enriquez et al.; Franklin Ikeda et al.; Inman and Silverstein). Some scholars have even examined particular metaphors used to reference writing centers (Pemberton; Fischer and Harris; Owens; Rollins). This knowledge about others’ perceptions and expectations has, in turn, led scholars to counter unrealistic expectations and to examine the ways in which we promote writing center services (Bishop; Hawthorne; Carino; Harri; Cirillo-McCarthy et al.). It has even allowed researchers to analyze the kind of language used to advertise writing consultations and how best to harness the power of such language (Hemmeter; Runciman; Harris; Cirillo-McCarthy et al.). This body of scholarship, based on collected evidence, has helped many writing center professionals to set appropriate expectations about individual consultations and to increase the success of this type of service. Similar data-driven research on writing groups is necessary if we are to do the same for this valuable type of writing support. It is for this reason that I decided to conduct my study exploring what potential writing group members envision before joining a group.

Theoretical Framework

In order to provide a theoretical framework to account for what writing group participants expect before joining a group I have pieced together several concepts from social cognitive theory, goal theory, and motivation in education. I have also borrowed terminology from all of these fields. In my study, I used the loose term expectation, rather than the more specific term goal, because I wanted to probe the full range of what writers envisioned before joining a group. However, there is much overlap among these terms in the literature. When comparing my study results to work done by other scholars, I am often forced to use expectations and goals interchangeably.

My use of the term expectation most closely aligns with social cognitive theory, in which outcome expectations, a concept highlighted by scholar Albert Bandura, means “the anticipated consequences of actions.” Bandura’s field defines goals broadly as “objectives that people are trying to accomplish” (Schunk et al. 140, 141). Particularly important for my study is the fact that behind every goal, consequence, or expectation is a particular purpose, or motivation. Motivation is not always apparent, but its presence can be inferred from actions. It is conceived of as the system of “inner forces, enduring traits, rewards, beliefs, and affects” supporting one’s actions or behaviors (Schunk et al. 4). My study was designed to examine both what writers expected before they join a group and, thus, what motivated them to join one.

The field of outcome expectations is a natural place to start when examining what one expects before engaging in a particular activity. Outcome expectations are often viewed as if-then statements: “If I engage in this activity, then I can expect a particular […] outcome” (Fouad and Guillen 134). Scholars in social cognitive theory often refer to outcome expectations in terms of actions, activities, or behaviors (Bandura; Fouad and Guillen; Aslam et al.). Aslam et al. point out that outcome expectations “cannot have a motivational effect until individuals are clear on how these outcomes are related to actions in their particular environment” (22). This is why I focused my interview and survey questions on particular writing group activities.

In addition to outcome expectations, Goal Orientation Theory can help us to make sense of writers’ goals and expectations when joining a group. Goal Orientation Theory is “concerned with why students want to attain a goal and how they approach and engage in [a] task.” The two most common goal orientations are mastery goal and performance goal orientations. Mastery goal orientation represents “a focus on learning [or] mastering the task according to self-set standards or self-improvement” (Schunk et al. 186, 187). Performance goal orientation, on the other hand, involves demonstrating an ability and being judged by others (Schunk et al. 187). In the case of my study, many participants revealed an interest in mastery goal orientation when they mentioned writing group activities that would lead to mastering certain writing-related skills.

Studies conducted on writers’ particular writing goals can also shed light on what we expect before engaging in a writing-related activity. For example, Zhang et al. examined student-generated writing goals for a particular writing assignment. The goals fell into three dimensions: general writing goals, genre writing goals, and assignment goals. In another study Soylu et al. applied achievement goal theory to writing by assessing students’ intentions for writing. The authors grouped student goals into three categories: mastery goals, performance approach goals, and performance avoidance goals. In these two studies there is again overlap with my own. All studies, my own included, revealed at least one set of students whose writing goals included gaining writing skills and a deeper understanding of writing, either in the form of general writing goals, mastery goals, or skill-based writing group activities. However, all scholars, like me, discovered other writers who expected and were motivated by many other things. I wanted to probe this full range of expectations and their effects on writing group participants.

Research Questions

In my study I was guided by the following research questions:

What activities do writing group participants anticipate before they participate in a writing group?

What activities do participants actually engage in during their groups?

Does a close alignment between expected writing group activities and actual group activities predict high satisfaction rates at the end of the semester?

Does a disconnect between expected writing group activities and actual group activities predict low satisfaction rates at the end of the semester?

PART II: STUDY DESIGN

My study was conducted at a writing center in a large public research and teaching institution in the Midwest. To assess writing group participants’ expectations about writing groups, actual group activities, and participant satisfaction levels, I used a combination of end-of-semester surveys and personal interviews administered over the course of six semesters.² Participants were graduate students (masters and doctoral) and visiting scholars from a variety of departments, years of study, ages, and linguistic and ethnic backgrounds. All groups were semester-long groups of up to 10 participants and were facilitated by myself or a graduate tutor from our writing center. Groups met once per week for two hours. Tables 1 and 2 (See Appendix A) provide information about number of participants, language, and group type for both the interviews and surveys administered.

Participant Surveys

I tried my best to create the writing groups survey with the concept of outcome expectations in mind. Rather than guess at what writing group activities participants might anticipate, I let the activities appear organically from correspondence between myself and potential writing group participants. I therefore created the survey based on 65 emails I received between 2014 and 2016. The emails came from students and scholars who were unfamiliar with writing groups and who were interested in receiving more information. Using the emails, an office assistant and I identified eight separate writing group activities in which these writers expected to engage: “working on my thesis or dissertation,” “jumpstarting my writing,” “receiving grammar help,” “giving/getting feedback,” “becoming motivated about my writing,” “finalizing and submitting writing for publication,” “learning about formatting and editing documents,” and “gaining accountability for my writing.” Using this list of anticipated writing group activities, we created a survey focused on expected and actual writing group activities and satisfaction levels. After human subjects approval was obtained, the surveys were administered both on paper and online at the end of each semester. They were sent to participants who dropped out of groups as well as to those who stayed in groups. See Appendix B for full survey.

Activity Categories

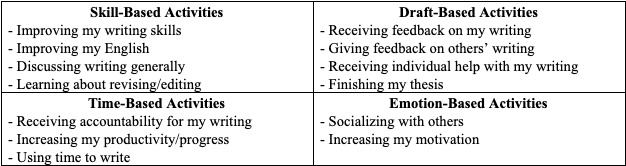

After I had recorded the survey responses, I used grounded theory to create a coding scheme for all the writing group activities mentioned. I coded each activity into one of the four categories that emerged from the responses: skill-based, draft-based, time-based, and emotion-based activities. I considered skill-based activities to mean improving one’s writing abilities and moving beyond particular writing projects. The draft-based category included working on specific writing projects (theses, dissertations, articles for publication) as well as the actions related to these specific projects. Another category I discovered focused on time-based activities. I considered these activities to be related to the participants’ desire to gain momentum, make progress, and move forward with their writing. One activity appeared to be emotion-based: “becoming motivated about my writing.” I considered this as related to a writer’s state of mind.

Participant Interviews

I also used the trends that emerged from the body of 65 emails to create open-ended questions for interviews. The questions were similar in scope to the survey questions and focused on expected and actual writing group activities and satisfaction levels. At the end of three different semesters writing group participants were invited to answer these questions in face-to-face interviews with me. All 10 interviews were recorded and then transcribed. See Appendix B for full set of interview questions.

Using the interview transcriptions I also created a coding scheme for the activities mentioned by the interviewees. Using two rounds of coding I pulled out all verb phrases associated with writing groups (like “meet new people” and “commiserate with other students”) and found common trends so that I could group the phrases together into larger common activities (like “socialize with others”). Lastly, I looked for even larger trends among these common activities until I grouped them into four main categories of writing group activities. Interestingly, the same expected writing group categories emerged from the interviews and from the surveys: skill-based, draft-based, time-based, and emotion-based activities.

PART III: FINDINGS

Expected Writing Group Activities: Participant Interviews

All 14 interview participants were asked what they expected of a writing group before joining. Table 3 (See Appendix A) provides a list of these activities sorted into categories. Overall, the skill-based activity category was the most heavily represented, with 40% of interview participants mentioning these types of activities. It appears that many of these writing group participants expected activities that would go beyond particular drafts and that would help them improve as writers and as speakers of English.

“Improving my writing skills” was the most popular activity. Group members talked in particular about improving writing structure, improving logic, improving clarity, improving academic writing style, improving punctuation, creating more complex sentences, and strengthening writing tone. For example, one writing group member told me, “Actually joining the writing group I expected to, you know, to improve my […] scientific writing, especially the way to like write in academic way.” “Receiving accountability for my writing” was the second most popular activity, named by five participants. “Receiving feedback on my writing” was mentioned by three participants, two of whom specified receiving feedback on their argument and on their thought process. “Increasing my motivation” and “socializing with others” were both mentioned by two participants. A member of one of the multilingual groups explained that “I kind of need motivation to get together regularly and each one discuss, have something to share. So I have to share my thesis and that kind of will motivate me.” Another participant had hoped to meet new people because, as she put it, “writing the dissertation is a very lonely assignment.”

Expected Writing Group Activities: Participant Surveys

Survey participants were also asked about the activities in which they had expected to engage. Table 4 (See Appendix A) provides a list of these activities sorted into categories. Overall, the writing group activities and activity categories were very similar to those named by interview participants; however, the survey participants ranked them in different ways. The category of draft-based activities was the most popular, chosen by 38% of respondents, followed by time-based activities (28%). The emotion-based and skill-based categories tied for last place with 17% each. “Gaining regular accountability for my writing” (time-based) and “becoming motivated about my writing (emotion-based) were the most frequently chosen individual activities.

The most interesting trend across all interview and survey results is the fact that in all cases the same four categories of activities emerged. The interview participants were not given a predetermined list of activities, yet they mentioned doing things in writing groups that aligned neatly with skill-based, draft-based, time-based, and emotion-based activities. The individual activities that were very similar in nature across the interviews and surveys were learning about editing, getting and giving feedback, gaining accountability, and increasing motivation. Each of these four activities fell under one of the four separate activity categories.

These four major activities and activity categories may have appeared multiple times because they hint at a core truth about writing groups, namely that several distinct types of groups exist for a reason. Expecting a group based on improving oneself as a writer differs greatly from expecting a group that will provide time and accountability for writing. Similarly, joining a group because one anticipates exchanging feedback about various drafts is clearly not the same as joining a group because one needs increased motivation. Obviously, writing group members may have more than one goal or expectation in mind. However, the overlap among actual activities can only go so far. Someone exchanging feedback cannot simultaneously use the time to write, for example. To writing center professionals this truth might seem apparent, but many novice writing group members may not take this into account. Writers may join a group with only one particular “category” in mind and quickly lose interest, motivation, or follow-through if they unwittingly join a group whose main purpose belongs to a different category.

Actual Writing Group Activities: Participant Interviews

Interview participants were asked what activities they actually ended up doing in their writing groups during the semester. Actual activities fell into three of the same categories as expected activities: skill-based, draft-based, and time-based. One new activity emerged: “giving oral presentations to group members” and was placed in the other category. Table 5 (See Appendix A) lists by category the writing group activities mentioned by the interviewees.

Draft-based activities appeared most popular (12 respondents), and no emotion-based activities were mentioned. Interestingly, only two responses referred to skill-based activities. It appears that, rather than improving skills or increasing motivation, most interview participants felt that they had engaged in activities related to working on and improving particular drafts of their own or others’ writing. The activities most frequently mentioned were “giving feedback” (6 respondents), “using time to write” (5 respondents), and “reading drafts” (3 respondents).

Actual Writing Group Activities: Participant Surveys

On the surveys, participants were also asked about the actual writing group activities in which they engaged during the semester. “Actual activities” listed on the surveys were the same as the “expected activities” and thus fell under the same four activity categories: skill-based, draft-based, time-based, and emotion-based. (See Table 4, Appendix A). As with the interviews, draft-based activities were chosen the most frequently, by 32% of respondents. However, unlike with the interview participants, survey participants reported that the activities in which they actually engaged were very close to those in which they had expected to engage. This could mean several things. Survey participants’ might have had particularly realistic expectations about writing group activities, or these participants might have done a particularly good job at placing themselves in an appropriate group. Alternatively, participants may have only elected to take the voluntary survey if they were already satisfied with what they did in their groups. The top three actual activities chosen were exactly the same as the respondents’ top three expected activities: “gaining regular accountability for my writing,” “becoming motivated about my writing,” and “working on my thesis or dissertation.”

Across all surveys and interviews we still find three of the same four categories: skill-based, draft-based, and time-based activities. There was, however, no mention of emotion-based activities among actual writing group activities. This, coupled with the emotion-based category’s low ranking among expected writing group activities, suggests that something is very different about this category. My guess is that participants are clear-eyed and practical when it comes to joining writing groups. These writers are more concerned with the concrete activities and immediate benefits of writing groups, valuing things like improved writing skills and increased production. Perhaps these writers view things like increased motivation, enhanced self-confidence, and decreased anxiety as welcome “side effects” of a group, rather than its main purpose. More research is clearly needed to fully flesh out this issue. In the meantime, I suggest we take care to separate out and clearly label emotion-based writing groups from other types of groups to avoid misaligned expectations.

Satisfaction Rates

There is much more to writing group expectations than lists of activities and rankings. Equally important is how participants feel about what they thought would happen and what actually did happen in their group. How do participants react when there are great similarities between what they expected and what they actually did in a writing group? What happens when there is a large disconnect?

Satisfaction Rates: Participant Interviews

Interview participants were asked to discuss how their actual writing group experience differed from their expectations. Their responses could be grouped under four main themes. There was mixing disciplines, meaning how the members reacted to having writers outside of their discipline in their group. Four participants mentioned how pleasantly surprised they were to be exposed to members from other disciplines or sub-disciplines and listed the benefits of this type of exposure: making writing understandable to outsiders, receiving diverse feedback from fresh perspectives, and learning about different disciplines. One participant discussed how the group helped writers “disconnect from the discipline to actually make you think objectively about what you are writing.” The theme of feedback referred to how members felt about the draft-based advice they received from their fellow writers and from their group’s facilitator. Four interview participants discussed how the feedback in the group surprised them. One appreciated the practical, specific suggestions; one enjoyed the active discussions; one liked receiving frequent feedback; and one valued the feedback from the group’s facilitator. Socialization indicated members’ feelings about being part of a group, and collaboration denoted how the writers actually worked with those group members. Two participants were happy with the unexpected social aspects of their groups: group camaraderie and creation of professional connections. One remarked, “Because writing dissertation is very, you know, lonely […] so sometimes it’s always very good to discuss with someone else or maybe just complain.” The other told me, “You know I see the folks in the [group] in other places […] So I did make some professional connections that I didn’t expect to by participating.” Two other members expressed their pleasure with the collaborative nature of their groups.

A few of the participants briefly mentioned ways in which they had been disappointed. One felt strongly that using group time to write was a “waste of time” because “you can do it at home.” Conversely, another participant wanted more time to write, saying that “maybe some student, if you ask them to write at home, they don’t do that.” Other concerns were high attrition rates, lack of discussion, and lack of guidance from the group’s facilitator. However, discussion of expected versus actual activities generally remained positive, with participants expressing overall satisfaction with their groups and appreciating the ways in which their actual experience diverged from their initial expectations.

Satisfaction Rates: Participant Surveys

Survey participants were asked to rate how satisfied they were with the activities in which they had actually engaged. I matched their satisfaction rates to the number of expected activities in which they actually engaged. Figure 1 (See Appendix A) presents these findings. It appeared that the majority of writing group participants (96%) were somewhat satisfied or very satisfied with their groups’ activities over the semester. I had hypothesized that if participants’ expected activities closely aligned with their actual activities the satisfaction rates would be high. I had also anticipated the opposite to be true: If participants’ expected activities were very different from their group’s actual activities, the satisfaction rates would plummet.

In the first case, I found that I was correct. When participants engaged in all of their expected activities, they were much more likely to be satisfied. Of those in this group (38 of the 72 participants), 95% rated themselves as somewhat satisfied or very satisfied with their groups’ activities. More surprising was what happened when many or all expected activities did not actually occur. Though this happened in few cases, even when there were three, four, or five expected activities that did not occur, all but one participant still rated themselves as somewhat satisfied. It is possible that the same phenomenon was at work here as with the interview participants. Those whose initial expectations were at odds with their actual experience may have ended up enjoying some or many of these unexpected differences. It is also possible that the participants who declined to take the survey appreciated these differences less.

Though it did not happen often that there was a large disconnect between expected and actual writing group activities, it is clear that it is still possible to have a positive experience and appreciate being in a writing group even if it does not meet one’s initial expectations. However, we must add an important caveat to this. Writing group members can only come to appreciate the differences between expectation and reality if they stick it out in their group. If the initial differences are too stark or the members too impatient, participants will likely not stay in the group long enough to learn this crucial lesson.

The Importance of Specific Drafts

One important point emerged from both the interviews and the surveys related to draft-based writing group activities and was noteworthy enough to merit its own brief discussion. Nearly all participants agreed that, in order for writing groups to be truly effective, one must have a specific draft to bring to the group. This may sound self-evident to many, but it is not. Every semester there are at least a few students and scholars who join our center’s writing groups hoping to improve their overall writing skills but who have no particular draft to work on. This almost always leads to frustration on the part of the group’s facilitator and the groups’ other members. It also often causes these members to drop out of the groups. It is for this reason that I probed the issue of specific drafts in writing groups in the interviews and surveys.

The Importance of Specific Drafts: Participant Interviews

All interview participants were asked whether or not they thought writing group participants should have a specific writing project or draft to work on in writing groups or if groups could still be useful without one. Ten of the 14 interview participants agreed that groups only work well when members have specific drafts. Several of those interviewed felt quite strongly about this, stating things like, “You should have something, I think. Otherwise, I don’t know. What are you gonna do?” or “There is so much more that can be received from the writing group when you have a specific draft.” Participants mentioned several drawbacks to participating in a group without a draft, such as the group being “too general” for its members or creating a lack of motivation. Three participants said, “It depends,” but still felt that groups were most effective when focused on drafts. Only one participant answered the question with an unqualified no. It appeared that most participants preferred to reach their writing group goals through working on particular pieces of writing.

The Importance of Specific Drafts: Participant Surveys

In order to probe this same issue in among survey participants, I asked them to rank the importance of working on particular writing projects in a writing group. Figure 2 (See Appendix A) shows the rankings in this case. We can clearly see that, as with the interview participants, an overwhelming majority of survey respondents (84%) ranked having a project to work on in a writing group as somewhat important or very important.

The issue of specific drafts in writing groups is most problematic in relation to novice writing group members with skill-based expectations. In some cases, these writers may envision particular drafts of their own writing when they anticipate improving their writing skills through a writing group, but what happens when they do not? These writers may soon drop out of the group or exert pressure on the group’s leader to act as a presenter, educator, or de facto workshop facilitator. It is up to each writing center how it tackles this issue, but it is important to keep in mind when forming writing groups, especially for anyone who is unfamiliar with how groups actually function and who expects to improve their overall writing skills.

Part IV: Main Trends and Recommendations

Through both interview and survey data we have seen what kind of activities potential writing group participants expected before joining a group as well as what actual activities these writers engaged in. We have noted what happened to participants’ satisfaction rates when there was overlap between these two sets of activities as well as how they reacted when there was divergence. Lastly, we have examined the importance of bringing specific drafts to a writing group. There were a few very clear and noteworthy trends that emerged from the overall findings in this writing group research project. It is my hope that these trends can offer important takeaways to those of us who create, run, and manage writing groups in an academic setting.

Main Trends

Four major categories of expected writing group activities – skill-based, draft-based, time-based, and emotion-based activities – emerged from the majority of interview and survey responses.

When participants’ expected activities aligned closely with actual activities completed in their groups, the participants were more likely to be satisfied with their groups.

Satisfaction rates did not decline greatly when expected writing group activities and actual activities did not align. Instead, participants often appreciated the unexpected ways in which writing groups diverged from their initial expectations.

Participants were in overwhelming agreement that writing group members must have a specific draft to work on in order for groups to be effective.

Based on the main trends that emerged from the interview and survey responses in my study, I offer the following recommendations for creating writing groups.

Recommendations

Before a group begins meeting, take care to explain clearly what a writing group is and the specific activities involved in it to any potential writing group members.

Consider creating separate writing groups based on skill-based, draft-based, time-based, and emotion-based activities. Take special care to separate out and clearly label any groups with largely emotion-based goals and purposes.

Alternatively, examine the activities in which potential participants expect to engage at your institution and tailor groups accordingly. You can then allow participants to self-select and choose groups based on their main goals and expectations.

Require participants in all types of groups to have specific drafts to work on.

PART VI: LIMITATIONS

This study had a small sample size, and results were unique to my own university’s and writing center’s context. We should be wary, therefore, of drawing large generalizations from these results. Additionally, a majority of the study’s participants stayed in their group during the entire course of the semester. Therefore, it is possible that the students and scholars who chose to participate in the voluntary surveys and interviews were group members who had a more positive experience overall. More feedback from dissatisfied members and from group dropouts might have changed the findings of this study in significant ways. Unfortunately, most of these group members declined to participate. Lastly, our writing center only offered groups to graduate students and to visiting scholars. Our results may not be applicable to undergraduate students, university staff, faculty, or community members.

PART VII: FINAL THOUGHTS

It is up to those of us in the writing center community to decide how we confront the problematic issues, misconceptions, and conflicting expectations involved in writing groups and how we educate potential writing group members about what actually takes place in a writing group. If we take nothing else away from this study, we should at least recognize that writers with different goals often expect very different kinds of writing groups. We should keep in mind this full range of potential goals, expectations, and motivations and use this knowledge to create and promote the right kind of group for each type of potential writing group participant. It is also up to us both to examine the assumptions and expectations related to writing groups in our own local contexts and to share these findings with one another on a larger scale. By continuing to add to this body of knowledge we can create groups that best meet the needs of our writers. This will allow us, in turn, to maximize the valuable benefits writing groups provide to their members. As is the case for all of the writing services we offer our clients, our ultimate aim should be to find ways for our writing groups not only to function, but to thrive.

NOTES

There are, however, a few exceptions. Maher et al. interviewed 18 writing group participants about their lived experiences in writing groups. Claire Aitchison also surveyed 24 past and current writing group members about their personal reflections on writing groups.

It is important to note that while I was able to obtain six full semester of data, I was only able to conduct interviews with participants over the course of the first three semesters of my study.

WORKS CITED

Aitchison, Claire. “Learning Together to Publish: Writing Group Pedagogies for Doctoral Publishing.” Publishing Pedagogies for the Doctorate and Beyond, edited by Claire Aitchison et al., Routledge, 2010, pp. 83-100.

Aitchison, Claire. “Writing Groups for Doctoral Education.” Studies in Higher Education, 34, 8, 2009, pp. 905-916, ProQuest, doi: 10.1080/03075070902785580.

Aslam, M.M., et al. “Predicting Student Academic Performance: The Role of Knowledge Sharing and Outcome Expectation.” International Journal of Knowledge Management, 10, 3, 2014, pp. 18-35, Link.

Bandura, Albert. Social Foundation of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice Hall, 1986.

Bishop, Wendy. “Brining Writers to the Center: Some Survey Results, Surmises, and Suggestions. The Writing Center Journal, 10, 2, 1990, pp. 31-44, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43444136.pdf.

Carino, Peter. “Reading Our Own Words: Rhetorical Analysis and the Institutional Discourse of Writing Centers.” Writing Center Research: Extending the Conversation, edited by Paula Gillespie et al., 2002, Erlbaum, pp. 91-110.

Cirillo-McCarthy, Erica, et al. “We Don’t Do That Here: Calling Out Deficit Discourse in the Writing Center to Reframe Multilingual Graduate Support.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 14, 1, 2016, pp. 62-71, Link.

Enriquez, D., et al. “To Define Ourselves or To Be Defined.” Weaving Knowledge Together: Writing Centers and Collaboration, edited by Carol Haviland et al., National Writing Centers Association P, 1998, pp. 107-126.

Fajt, Virginia, et al. “Feedback and Fellowship: Stories from a Successful Writing Group.” Working with Faculty Writers, edited by Anne Ellen Geller and Michelle Eodice, UP of Colorado, 2013, pp. 163-174.

Farkas, Carol-Ann. “’Idle Assumptions are the Devil’s Playthings’: The Writing Center, The First Year Faculty, and the Reality Check.” Writing Lab Newsletter, 30, 7, 2006, pp. 1-5.

Fischer, Katherine and Muriel Harris. “Fill ‘er Up, Pass the Band-Aids, Center the Margin, and Praise the Lord: Mixing Metaphors in the Writing Lab.” The Politics of Writing Centers, edited by Jane Nelson and Kathy Evertz, Heinemann, 2001, pp. 23-36.

Fouad, Nadya, and Amy Guillen. “Outcome Expectations: Looking to the Past and Potential Future.” Journal of Career Assessment, 14, 1, 2006, pp. 130-142, doi: 10.1177/1069072705281370.

Franklin Ikeda, John, et al. “English Education Within and Beyond the Writing Center: Expecations Examples, and Realizations.” Writing Lab Newsletter, 24, 8, 2000, pp. 10-13.

George, Diana. “Working with Peer Groups in the Composition Classroom.” College Composition and Communications, 35, 3, 1984, pp. 320-326, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/357460.pdf.

Gradin, Sherrie, et al. “Disciplinary Differences, Rhetorical Resonance: Graduate Writing Groups Beyond the Humanities.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 3, 2, 2006, pp. 1-6, Link.

Graham, Kathryn, et al. “Writing Without Teachers, Writing With Tutors.” Writing Lab Newsletter, 18, 7, 1994, pp. 7-8.

Haas, Sarah. “Pick-n-Mix: A Typology of Writers’ Groups in Use.” Writing groups for Doctoral Education and Beyond, edited by Claire Aitchison and Cally Guerin, Routledge, 2014, pp. 30-47.

Harris, Muriel. “Making Our Institutional Discourse Sticky: Suggestions for Effective Rhetoric.” The Writing Center Journal, 30, 2, 2010, pp. 47-71, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43442344.pdf.

Hawthorne, Joan. “’We Don’t Proofread Here: Re-visioning the Writing Center to Better Meet Student Needs.” Writing Lab Newsletter, 23, 8, 1999, pp. 1-6.

Hayward, Malcolm. “Assessing Attitudes Towards the Writing Center.” The Writing Center Journal, 3, 2, 1983, pp. 1-10, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43444105.pdf.

Hemmeter, Thomas. “The ‘Smack of Difference’: The Language of Writing Center Discourse.” The Writing Center Journal, 11, 1, 1990, pp. 35-48, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43442593.pdf.

Inman, Arpana and Michael Silverstein. “Dissertation Support Group: To Dissertate or Not is the Question.” Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 17, 3, 2003, pp. 59-69, doi: 10.1300/J035v17n03_05.

Maher, Damian et al. “’Becoming and Being Writers’: The Experience of Doctoral Students in Writing Groups.” Studies in Continuing Education, 30, 3, 2008, pp. 263-275, doi: 10.1080/01580370802439870.

Masiello, Lea and Malcolm Hayward. “The Faculty Survey: Identifying Bridges Between the Classroom and the Writing Center.” The Writing Center Journal, 11, 2, 1991, pp. 73-79, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43440550.pdf.

Moss, Beverly et al., editors. Writing Groups: Inside and Outside the Classroom, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004.

North, Stephen. “The Idea of a Writing Center.” College English, 46, 5, 1984, pp. 433-446.

Owens, Derek. “Hideaways and Hangouts, Public Squares and Performance Sites: New Metaphors for Writing Center Design.” Creative Approaches to Writing Center Work, Hampton P, 2012, pp. 71-84.

Pemberton, Michael. “The Prison, the Hospital, and the Madhouse: Redefining Metaphors for The Writing Center.” Writing Lab Newsletter, 17, 1, 1992, pp. 11-16.

Phillips, Talinn. “Graduate Writing Groups: Shaping Writing and Writers from Student to Scholar.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 10, 1, 2012, pp. 1-7, Link.

Pololi, Linda, et al. “Facilitating Scholarly Writing in Academic Medicine: Lessons Learned From a Collaborative Peer Mentoring Program.” Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19, 1, 2004, pp. 64-68, ProQuest, https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21143.x.pdf

Rodis, Karen. “Mending the Damaged Path: How to Avoid Conflict of Expectation When Setting up a Writing Center.” The Writing Center Journal, 10, 2, 1990, pp. 45-57, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43444137.pdf.

Rollins, Anna. “Equity and Ability: Metaphors of Inclusion in Writing Center Promotion.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13, 1, 2015, pp. 5-6, Link.

Ruggles Gere, Anne. Writing Groups: History, Theory, and Implications. Southern Illinois UP, 1987.

Ruggles Gere, Anne and Robert Abbott. “Talking About Writing: The Language of Writing Groups.” Research in the Teaching of English, 9, 4, pp. 362-385, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40171067.

Runciman, Lex. “Defining Ourselves: Do We Really Want to Use The Word Tutor?” The Writing Center Journal, 11, 1990, pp. 27-34, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43442592.pdf.

Schunk, Dale, et al. Motivation in Education: Theory, Research and Applications. Pearson, 2014.

Soylu, Meryem et al. “Secondary Students’ Writing and Achievement Goals: Assessing the Mediating Effects of Mastery and Performance Goals on Writing Self-Efficacy, Affect, and Writing Achievement.” Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2017, pp. 1-11, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01406

Spear, Karen. Sharing Writing: Peer Response Groups in English Classes. Boynton, Cook Publishers, 1988.

Westbrook, Evelyn. “Community, Collaboration, and Conflict: The Community Writing Group As Contact Zone.” Writing Groups Inside and Outside the Classroom, edited by Beverly Moss et al., Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004, pp. 229-248.

Zhang, Fhui, et al. “Charting the Routes to Revision: An Interplay of Writing Goals, Peer Comments, and Self-Reflection from Peer Reviews.” Instructional Science, 45, 5, 2017, pp. 679-707, doi: 10.1007/s11251-017-9420-6.

Appendix A: Tables and Figures

Table 1: Participants, Language, and Group Types (Interviews)

Note: Some interviews were conducted individually and some in small groups.

Table 2: Participants, Language, and Group Types (Surveys)

Table 3: Expected Writing Group Activities and Activity Categories (Interviews)

Table 4: Expected Writing Group Activities and Activity Categories (Surveys)

Table 5: Interviews: Actual Writing Group Activities and Activity Categories

Figure 1: Surveys: Participants’ Satisfaction Rates

Figure 2: Surveys: Importance of Working on Writing Projects

Appendix B

Writing Groups Survey

Semester: ___________________

Type of group: Humanities Social Sciences Sciences Multilingual Publishing Accountability

Did you stay in the group all semester or drop out ? ____ Stayed all semester ___ Dropped out

If you dropped out – why ? _______________________________________________________

Are you a multilingual writer (English as a second language)? _____ Yes _____ No

Department: ___________________________________

Year of Study: __________________________________

Are you a masters or Ph.D. student? ______ Masters _____ Ph.D.

1. What activities did you expect to engage in prior to joining your writing group? (circle all that apply)

Working on my thesis or dissertation

Jumpstarting my writing

Receiving grammar help

Giving feedback to group members and getting feedback from group members

Becoming motivated about my writing

Finalizing and submitting writing for publication

Learning about formatting and editing documents

Gaining regular accountability for my writing

Other: ____________________________________________________________

2. What activities did you actually engage in during your time in the writing group? (circle all that apply)

Working on my thesis or dissertation

Jumpstarting my writing

Receiving grammar help

Giving feedback to group members and getting feedback from group members

Becoming motivated about my writing

Finalizing and submitting writing for publication

Learning about formatting and editing documents

Gaining regular accountability for my writing

Other: ____________________________________________________________

3. How satisfied are you with the activities you actually engaged in during your time in the writing group?

Not satisfied at all

Somewhat unsatisfied

Neutral

Somewhat satisfied

Very satisfied

4. How important was working on your particular writing projects throughout the semester?

Not important at all

Somewhat unimportant

Neutral

Somewhat important

Very important

5. How well do you believe you fit into your chosen writing group?

Very poorly

Somewhat poorly

Neutral

Somewhat well

Very well

6. Based on your experience, how necessary are graduate writing groups on our campus?

Very unnecessary

Somewhat unnecessary

Neutral

Somewhat necessary

Very necessary

7. Rate the overall effectiveness of your group

Very ineffective

Somewhat ineffective

Neutral

Somewhat effective

Very effective

8.Other comments about your writing group experience:

Writing Groups Interview Questions

What were your expectations of a writing group prior to joining this semester?

What activities did you engage in in your writing group?

How was your writing group different from your expectations?

What was your reaction to this difference? Was it positive, negative, or neutral?

Do you think writing group participants should have specific writing projects (papers, articles, applications, etc.) to submit to their group? Or can groups be helpful to participants who don’t have specific texts to submit?

If you think groups can be helpful to participants who don’t have specific texts to submit, what are some activities that could be useful?

What other thoughts do you have about writing groups?