Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol 18, No 2 (2021)

Turf Wars, Culture Clashes, and a Room of One’s Own: A Survey of Centers Located in Libraries

Lindsay Sabatino

Wagner College

lindsay.sabatino@wagner.edu

Maggie M. Herb

SUNY Buffalo State College

herbmm@buffalostate.edu

Abstract

Across college and university campuses, librarians and writing center workers are increasingly finding the trajectories of their academic units intersecting, both physically and institutionally. While both library and writing center scholarship have investigated this trend, research has primarily focused on specific collaborative efforts or theoretical bases for forming partnerships; the issue of centers being physically housed in libraries and the implications of sharing space have been largely unexplored. The researchers present the results of a survey of more than 100 center directors whose centers are located in libraries, moving beyond the common focus on collaborative undertakings by asking participants about theoretical, pedagogical, and practical concerns that stem from centers physically relocating to libraries. Specifically, the researchers focus on participants’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of centers being physically located in libraries and reflect on the greater implications of this trend for the writing center field, particularly how physical space and institutional location can impact the pedagogies of the writing center.

Across college and university campuses, librarians and writing center workers are increasingly finding the trajectories of their academic units intersecting, both physically and institutionally. The National Census of Writing, which collects data on Writing Centers and Writing Programs, found in its 2017 census that at four-year institutions, 56% of respondents indicated that the physical location of their writing center is a library. This was a notable jump from the 2013 census, in which 45% of respondents at 4-year institutions reported that their center was located in a library. Both the 2013 and 2017 census numbers represent a significant increase from the only previous large-scale survey of this sort—the Writing Center Research Project, which reported in its 2003-2004 edition that 16% of writing centers surveyed were located in libraries (Griffin et al.). The overall trend toward consolidated models for tutoring and other student services into Learning Commons or similar models has no doubt helped to shape this trend, as often these “one stop” centers are located within the institution’s library.

Libraries becoming sites that house tutoring and other student services are in many ways the natural conclusion—and solution—to the necessary transformation that academic libraries have undergone over the last 50 years. As James Elmborg characterizes it, twenty-first century academic libraries have “self-consciously redefin[ed] themselves, moving away from the warehousing definitions of the past and toward instructional models” (4). This deliberate turn toward sites of learning and interaction rather than information repositories has allowed academic libraries to reinvent their purpose and relevance for a new age in which resources are increasingly electronic and student needs have changed.

As libraries shift their identities to sites of learning and instruction, the parallels between the work of librarians and the work of writing center practitioners have become increasingly visible. These connections are explored to various degrees in both library and writing center scholarship. Library scholarship, in particular, tends to advocate for the benefits of collaboration—and even co-location—between libraries and writing centers. Rachel Cooke and Carol Bledsoe asks their readers to “consider the advantages of a writing center housed in a library,” such as the “convenience of ‘one-stop-shopping’ for help with research and writing” (1-2). They also offer suggestions on how co-location can allow librarians and writing center workers to collaborate through cross training, joint programming, or team-teaching. Mary O’Kelly et al. suggest that libraries should apply the writing center peer tutor model to the library, training student tutors to assist peers with the research process. Elmborg argues that libraries and writing centers are natural institutional allies, “living parallel lives, confronting many of the same problems and working out similar solutions, each in their own institutional context” (1). Other library scholarship documents the various models and types of center-library collaboration (Mahaffy; Ferer; Jackson).

Writing center scholarship that focuses on centers and libraries similarly tends to document specific collaborative efforts, though at times with a more critical eye. Jean-Paul Nadeau and Kristen Kennedy characterize writing center/library relationships as potentially “contentious” as “librarians and writing center directors draw deep disciplinary lines between the work they do” (4). However, after detailing their writing center’s collaborative workshops with the library, they note the need for a better understanding of one another’s disciplinary work and the importance of developing strong alliances, grounded in their shared “service positions” in the university and shared desire to encourage student active engagement and autonomy in the research/writing process (6). Laura Brady et al. similarly detail the results of collaboration among writing faculty, librarians, and the writing center to pilot a team-teaching approach to information literacy that emphasized the connected, discursive nature of reading, writing, and research. Ultimately, their collaborative project “encouraged writing faculty, tutors, and librarians to re-examine professional and disciplinary boundaries, and resulted in new assignments and activities that successfully engage[d] students” (Brady et al.).

Certainly, the most detailed treatment of library and writing center collaborations is James Elmborg and Sheril Hook’s collection, Centers for Learning: Writing Centers and Libraries in Collaboration, featuring chapters, described as case studies, each written by pairs of librarians and center administrators detailing their collaborative efforts and presenting a theoretical basis for forming partnerships. Unlike other scholarship, this collection features the voices of both librarians and writing center professionals and presents the case studies with nuance—deliberately looking at challenges as well as successes.

Still, this collection—and the other scholarship published in both writing center and library journals—does not focus in any great detail on what comes after a collaboration or relationship is established, especially in the context of co-location. While existing research makes clear the rich possibilities associated with writing center/library collaborations, the ongoing, day-to-day pedagogical effects of writing centers and libraries sharing a location are largely left unexplored.

As two directors who have each worked in multiple centers housed in libraries, we have had a wide range of experiences regarding the nature of our collaboration with and connection to our library departments. These differences—paired with the lack of scholarship examining the everyday realities of sharing spaces—have compelled us to investigate the experiences of other library-based center directors. A need exists to examine writing center/library relationships in the broader context of writing center work and from the specific perspectives of writing center practitioners. Moreover, scholarship needs to look beyond documenting collaborative undertakings and instead explore theoretical, pedagogical, and practical concerns that stem from centers physically relocating to libraries, particularly in light of this apparent trend reflected in our findings. Acknowledging the increasingly multidisciplinary nature of writing center work, we deliberately broadened the scope of our study to include not only writing center directors, but also directors of centers that focus on or include tutoring in overlapping disciplines. This includes speech, communication, or multimedia, as well as directors of writing centers that exist as part of a consolidated model. Thus, the purpose of our research is to examine the benefits and challenges of writing centers or similarly modeled centers physically located in libraries and reflect on the greater implications of this trend for the writing center field.

In this article, we discuss our survey of more than 100 centers located in libraries, beginning with a description of our methodology, drawn from grounded theory. We then provide a brief summary of our results before examining survey responses that pertain to the participants’ perceived benefits and challenges of co-location and engaging in a broader discussion of these effects on center pedagogy.

Methods

When we began this research, we had both recently begun directing centers located in libraries. As we worked to negotiate the changes and challenges this brought to our respective centers, we often found ourselves consulting each other, as well as writing center colleagues at other institutions, for suggestions and support. As we read messages on our professional listservs and chatted with colleagues at conferences, we sensed that center-to-library relocation may be part of a growing trend; more and more often, we noticed other center directors reaching out for help from our professional community, wondering how best to self-advocate for their center’s needs or help library colleagues to understand their work. Unable to find resources and scholarship that discussed this possible trend and, more importantly, the actual impact of library relocation on writing centers, we designed this study as a starting point. Specifically, our goal was to learn about the circumstances surrounding a center being located within their campus’s library, the experiences of the center with co-location, and how those experiences impact writing center pedagogy. As a result, our study was guided by three corresponding research questions:

What factors influence centers being housed in libraries?

What benefits and challenges do centers (including their directors, tutors, and tutees) experience as a result of these moves?

What impact do center/library partnerships have on center pedagogy?

Data Collection

In 2015, we conducted an IRB-approved, confidential, 17-question survey of 104 directors whose centers are located in their institution’s library. The results were collected through Qualtrics. This survey consisted of a combination of multiple choice and open-ended questions that collected basic demographic and institutional data as well as questions that invited participants to describe their experiences directing a center located in a library.

Site and participant selection

Participants were solicited through professional listservs, both those frequented by writing center professionals (WPA-L and WCenter) as well as others such as LRNASST-L (used by learning assistance professionals at large) and INFOCOMMONS-L (focused on discussion of information commons and other assistance centers within libraries). We also put out a call for participants on the International Writing Center Association blog. We crafted our call to include the many varying forms writing centers take; for example, some writing centers are folded into learning commons where writing tutors work alongside tutors from other disciplines. Other writing centers have expanded their services to take on communication, speaking, and digital projects— at the time we began this research, we both were directors of such centers. While we sought to include directors of these nontraditional centers in our research by circulating our call for participants widely, the largest group of responses came from writing center directors.

One hundred and four center directors responded to our call for participants. Figure 1 (See Appendix) shows that the majority of our participants (85%) reported directing centers at 4-year institutions, 9% at 2-year institutions, and the remaining 6% were unreported. Additionally, as figure 2 illustrates (See Appendix), participants more evenly reported from private (47%) and public institutions (38%), with the remaining 15% unstated. Moreover, numerous organizational models were represented, from centers physically located in a library but reporting to and/or funded through academic departments to models where the center director reports to a library dean and/or is considered library faculty/staff.

Data Collection

Grounded theory informed our approach to analysis due to the lack of previous research that studies the causes and effects of centers moving into libraries. This bottom-up approach allowed us to be flexible and discover meaning from this data. As Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin explain, grounded theory “offer[s] insight, enhance[s] understanding, and provide[s] a meaningful guide to action” (12). Thus, after we quantified general demographic and institutional data, we began preliminary examination of selected open-ended questions. In this article, we focus our attention in particular on two main questions from our survey that most directly addressed our research questions:

“For what reasons did your center/commons move to the library?”

“What have been the challenges and benefits of your center/commons being located in the library?”

For both of these open-ended questions, we individually completed an initial stage of open coding with participants’ descriptive data, breaking their responses into short words or phrases that “symbolically assig[n] a summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute” (Saldaña 3). These codes assigned “interpreted meaning” to each data point, allowing us to take the first steps toward “analytic processes” (Saldaña 4). During this process, we each developed a detailed description for each code. Then, we met virtually to compare these codes, their operational definitions, and develop a refined finalized list of both. We then moved on to the focused coding stage, which Kathy Charmaz explains “requires decisions about which initial codes make the most analytic sense to categorize [the] data incisively and completely” (qtd. in Mertens 428). With the new set of codes, we labelled and identified meaningful data and distinguished relationships, patterns, trends, and themes, each testing the codes to ensure greater reliability. After completing this re-coding process individually, we met again virtually to develop a final coded document for the questions.

Through this coding process, we recognized pattern codes, which allowed us to group information, developing major themes that emerged from the data. As Donna Mertens states, “If a researcher is using a grounded theory approach, the focused coding will lead to identifying relations among the coding categories and organizing them into a theoretical framework” (428). This process allowed us to quantify trends and patterns as reported in the directors’ perceptions of their experiences with their center and the library. These representative themes comprise our discussion section.

Summary of Research Results

At the beginning of the survey, we asked participants to identify how long their center has been in existence and how long it has been located in the institution’s library. Figure 3 (See Appendix) illustrates that the majority of our participants reported directing centers that have been in existence for more than 10 years (61%), whereas figure 4 (See Appendix) shows that the majority of these centers moved into the library less than 10 years ago (75%). This data further substantiates the increasing trend of centers moving into libraries that we observed when comparing the data from the Writing Center Research Project (2003-2004) with the National Census of Writing (2013-2014; 2017).

“For what reasons did your center/commons move to the library?”

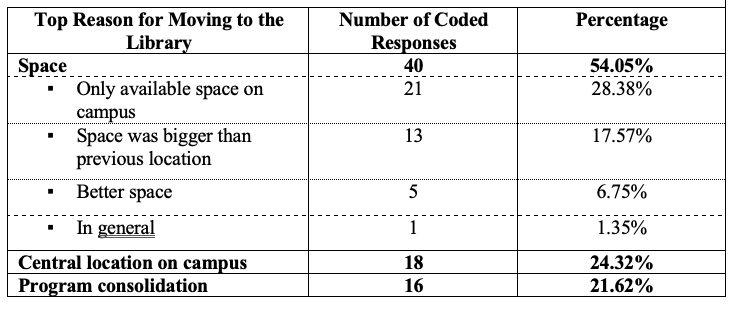

Of the 104 participants who filled out our survey, 102 responded to this question. From these responses, we determined and defined 31 codes. The top reasons that centers moved into libraries were associated with the need for space, the central location of the library on campus, and program consolidation (See Table 1 in Appendix).

Most notably, responses to this question overwhelmingly revolved around themes of the physicality of the center—both concerning the space of the center itself and where it is located on campus. In addition to pragmatic reasons, participants noted the central location of the library as a reason for the move, including those who described the library as a “hub” on campus, or “where the students hang out,” as well as those who described the library as “centrally located on campus.”

Lastly, center directors stated that the move to the library was a result of program consolidation in which the center moved to the library to be located with other tutoring or student services, either centralized together as one unit or in close proximity to one another.

“What have been the challenges and benefits of your center/commons being located in the library?”

Of the 104 participants who filled out our survey, 93 responded to this question about challenges and benefits. From these responses, we initially broke up the codes into separate categories for benefits and for challenges. We found a much greater similarity among the benefits, with the challenges comprising a more varied list. We determined and defined 22 codes for benefits and 34 codes for challenges.

Benefits

The top identified benefits of the center being located in the library were access or proximity to resources, library environment, central location, and increased visibility (See Table 2 in Appendix).

Of the benefits that participants named, the most frequent responses were related to access or proximity to resources—both physical resources, such as reference books or technology, and resources in the form of individuals, such as reference librarians.

The second most frequent responses related to the environment of the library, which we classified into two subcategories: physical and institutional. The benefits of the physical environment of the library included aspects such as added security for tutors working in the evenings or access to library facilities. The institutional environment benefits include the library being an academic (rather than remedial) space and not being associated with any one discipline, making it a neutral, multidisciplinary ground.

The third most common benefit focused on the centralized location of the library, both as a place where students congregate and its central location on campus. Relatedly, 18 more responses mentioned increased visibility in general as another benefit.

Challenges

As previously mentioned, the stated challenges offered a more varied list of codes than the benefits. The top challenges that were coded include: space, ownership or authority, and misperceptions of the center. As seen in Table 3 (See Appendix), the challenge most often named was related to space, which yielded 61 responses—a sharp contrast in frequency from the next-most mentioned challenge, lack of ownership or authority, which was mentioned only 16 times.

The most common challenge associated with space was difficulties sharing space with the library or librarians (See Table 3 in Appendix). Indeed, some participants even referred to this issue as a “turf war.” Other space issues were related to a lack of separate space for the center and accompanying issues, such as lack of security (because of no doors or walls) and lack of privacy for tutoring sessions. One respondent mentioned the need to “police the space” and another wrote “we cannot put a lock on the doors to the Center, therefore at night after we close (and the library is still open) we've had some problems with items going missing, students using the printers free of charge, moving things around, and the like.”

Although issues of space dominated the challenges described, the director or center’s lack of ownership/authority was the next most frequent category of responses. Here respondents described situations where the library administration rather than the center director had decision-making authority over the center’s policies, space, or practices.

Lastly, participants identified misperceptions about the center as a challenge they face, including those regarding services, which ranged from misunderstandings about the purpose/pedagogy of center (such as being perceived as a remedial space) to librarians not seeing the center as “capable of helping with research,” to students thinking they need a completed draft before receiving assistance. Additionally, misperceptions about the space focused on issues resulting from the space being open—lacking walls, doors or other demarcations to separate it from the work and study spaces in the rest of the library. This open-access and open floor plan design resulted in a lack of understanding of its use both from students who would use the space as it was not intended (such as for sleeping, group study, or printing) and from librarians who had expectations of the center space being available to all students, regardless of whether they were using the center’s services.

Discussion: Reasons for the Move

Pragmatic concerns

Concerns, such as space, location on campus, program consolidation, and library environment, largely seemed to guide relocation. We characterize these concerns collectively as pragmatic, as they are driven by practical circumstances beyond the purview or control of the writing center or the library. In many cases, centers initially moved into libraries because they contained the only space available on campus. As one participant explained, “We needed more space. It was the only available option the University could afford.” Many others noted the central location of the library as a reason for the move—with the expectation of increased visibility and student usage as a result. While scholarship (Cook and Blesdoe; Currie and Eodice; Mahaffy) highlights writing center co-location as an opportunity for centers and libraries to learn about each other’s roles, collaborate, and complement each other’s services. However, our results showed very few responses—only six—indicating that a center relocated for the specific purpose of developing a partnership or collaboration with the library. Instead, these moves were primarily about real estate: the centers needed space and the library had it.

Program consolidation

Perhaps not surprisingly, participants’ responses reflected the impact of the “one stop” student services trend seen at colleges and universities across the country (Ousley). For many, their center was not just relocated to a library, but was simultaneously folded into a learning commons or student success center as a result of a broader campus consolidation initiative. Often, this centralization was accompanied by a renovation of library space: “The college decided to move all services to one central location. The library was renovated to house them all.” Another characterized the library dean desiring that the library “feel like a mall full of services.”

Discussion: Benefits and Challenges

As we studied the trends among participants’ responses to the benefits and challenges questions, we saw several significant themes and contrasts emerge, particularly when we also considered not only what these responses said, but what they did not say. As outlined below, while the responses indicated that relocation improved access to operational resources, and potentially increased the visibility of the center, the challenges respondents discussed appear to have a far greater impact on the pedagogy of the center.

Proximity to resources

The top benefits cited by participants were access or proximity to resources; we chose the words access and proximity deliberately to describe these responses. Consider the following selection of representative responses: “easier access to library resources,” “the reference desk is 20 feet from our door,” “the tutors/tutees have access to computers and printers which may be needed for some of the work they are doing together.” On one hand, these responses indicate that the most common benefit is one that relates to the intellectual and operational work that takes place in the center and its connection to the resources available in the library, reinforcing the notion of a natural connection between the two units. Nonetheless, it stands out that these responses focused specifically on access and proximity, often in the abstract or hypothetical. Scholarship on center/library partnerships often advocates for deliberate and ongoing institutional collaborations because of their benefit to students’ writing and research processes, by making visible their interwoven, discursive nature (Nadeau and Kennedy; Elmborg and Hook; Zauha); while we created a code to collate any responses that mentioned deliberate collaboration with librarians as a benefit of the move, this code applied to only a handful of responses. Furthermore, only a few of the responses discussing access or proximity to resources specifically mentioned the impact of these resources on its center’s pedagogical approaches. In other words, for many of our participants, the benefit of being located in the library is simply being near resources like books, computers, or reference librarians, or accessing them more easily, rather than collaborating with library staff and tutors to use these resources in new or innovative ways.

Location, visibility, and control

Each of the top four benefits that participants named related in some way to the physicality of the center. The top two most frequently mentioned benefits—access to resources and environment of the library—relate to the specific academic or institutional benefits that proximity to or presence in the library offers; again, here participants cited easy access to library resources, from books, journals or computers to reference librarians. Others discussed the physical or academic environment, from later hours or extra security to the multidisciplinary/neutral academic space of the library. The remaining two most named benefits similarly focus on physical location, but in these responses—central location and visibility—the focus shifts from the academic particulars of the library’s physical space and simply to the notion of the center having a greater or more significant physical presence on campus due to its location in the library.

This near-singular focus on the benefits of physical location and increased proximity/visibility among participants is notable—and perhaps due in part to the fact that the majority of participants moved to the library recently. Some participants stated that their increased visibility also contributed to increased traffic. As one participant stated: “the regular traffic in the Library brings in users who might not otherwise seek out the services located in the commons.” The oft-cited image of a writing center in a basement or a makeshift classroom may now be cliché but has remained a reality for many through the years; as such, the prospect of increased visibility in a prominent location on campus is not insignificant. Indeed, as Carolyn Peterson Haviland et al. argue, “Location is political because it is an organizational choice that creates visibility or invisibility, access to resources, and associations that define the meanings, uses, and users of designated spaces” (85). Still, when we reviewed the challenges participants faced, we can see another side of the coin emerging—the potential limits and consequences of visibility.

Participants’ challenges related to location continued to return to the concept of control. A writing center space being in a prominent or desirable location may certainly positively impact perceived legitimacy; however, as our participants’ responses indicate, visibility and location alone are not necessarily or exclusively indicative of whether a center’s work or expertise is valued or understood. Throughout participants’ discussion of challenges, a thread appears which speaks to a lack of control over the center space and a lack of understanding from others—from students to library faculty—of the work that takes place there, as evidenced in challenges ranging from spaces lacking walls/privacy to the inability of directors to make needed policy decisions. Many of the conflicts that these center directors reported seemed to stem from librarians’ lack of understanding of the pedagogical work of tutoring. As one participant described these conflicts “The library has a culture of silence, quiet contemplation, and individual study; the writing center has a culture of collaboration and verbal communication. These two ideologies do not always mix. Since the library is the writing center's ‘landlord’ the writing center staff typically lose the argument when it comes to quiet versus verbal communication.” In short, from these responses, it appears that increased visibility and a more prominent physical positioning on campus do not necessarily indicate a resultant increase in institutional respect for the center or the director—and may perhaps lead to less, if the tradeoff of a better location on campus ultimately results in a significant loss of control of that space and jeopardizes the pedagogy of the work that takes place there.

The Conundrum of space

As previously mentioned, the majority of our participants reported that their move to the library was compelled in part by reasons related to inadequate space. It is particularly troubling, then, that space was reported as the biggest challenge participants faced after they relocated to the library. Approximately 50% of participants stated that either space, location within the library, or both were a challenge. Most notably, we coded 40 occurrences of directors stating space as the reason their center moved to the library, yet only 18 occurrences listing space as a benefit of the move; in contrast, we coded 61 occurrences of directors stating that space was a challenge. In particular, participants repeatedly cited challenges with spaces that were inadequate for the work of the center—whether due to the space itself or being forced to negotiate sharing “turf” with resistant library colleagues. Many participants reported not having control over the space or explicitly being told “no” when asked to make the space their own. Thus, some of these moves—meant to alleviate or address problems of space—may have instead prompted new sets of space-related challenges.

Although many of these partnerships originated in part to address a practical concern (such as space), we see thata center moving to the library does not eliminate—and might even exacerbate—the issue. In the end, while most participants acknowledged that centers moving to libraries comes with a mix of benefits and challenges, we are concerned that the challenges appear to have a greater pedagogical impact.

Discussion: Impact on Center Pedagogy

The question of how center and library partnerships have impacted center pedagogy is particularly important given how much literature concerning these partnerships documents specific collaborative efforts, but not their sustained, long-term effects nor the impact of sharing space on these collaborations. While few participants directly stated that their move impacted center pedagogy, many of their comments carry significant pedagogical implications, from the space-related challenges profoundly affecting tutoring, to the lack of authority that many directors experienced in making decisions for their center.

Collaboration and productive noise

Overall, respondents identified significant location issues related to noise. As one participant wrote: “We’re located on the quiet floor and have to be careful about sounds from tutorials and staff meetings escaping into the open study areas.” The issue of noise was further exacerbated for participants whose centers did not have private or separate tutoring spaces at all within the library. Participants identified numerous challenges with being located in an open rather than private space, such as library patrons or staff telling them to be quiet, lack of privacy for tutoring sessions or sensitive conversations, and issues of security/safety resulting from no doors or walls. We find these responses particularly troubling, since writing centers are places of interaction, conversation, and collaboration. Collaboration produces noise and, as Russell Carpenter states, “conversation generated between and among students is productive and even desirable” (70). In turn, the location and design of writing center spaces should help cultivate collaboration and not diminish it.

Further, we would argue that being interrupted during a tutoring session to be asked to keep the volume down could make writers uncomfortable about seeking out assistance; this could be intensified if the student is already self-conscious about their writing or language, has a learning or cognitive disability, or is sharing a personal or sensitive topic. As we have noted elsewhere, “When tutors or writers do not feel comfortable having conversations about writing because they are perceived as too loud, their tutoring practices or openness to share may be squashed...The significance of this issue was represented by many participants recommending soundproof walls, having real walls that go to the ceiling (not cubicle walls), and being placed away from quiet spaces.” (Herb and Sabatino 25). These issues described by participants represent much more than a simple inconvenience, but rather a pedagogical disruption and a fundamental disrespect for writing center work. We agree with Elizabeth Boquet, who argues that what gets qualified as productive noise varies depending on who the receiver is:

What gets labeled as noise is essentially a value judgement, a means of dismissing signals a chaotic, disruptive, meaningless, uninteresting. So when [a colleague] refers to the work taking place in our writing center as “noisy,” it means he doesn't hear what I hear. It means he's not listening the way I'm listening. He has, effectively, written off what those writers have to say, how they say it, and what he might actually learn from it. (66)

If writing centers are located in an environment—such as a library—that has a profoundly different conception of “productive noise,” this value judgement that Boquet describes can affect the work of tutoring in many ways—whether making tutors and writers less able or willing to speak freely or distracted by concerns about noise, or positioning them at odds with their library colleagues, rather than in partnership. Since many participants also mentioned issues with turf wars and space sharing, it appears that for some, the final determination about what gets classified as productive noise comes from the library, disregarding the center’s stance. If writing centers are not located in spaces that respect the productive noise that accompanies their work, the collaborative practices that form the very building blocks of this work are threatened.

Discussion: Ownership and Space Design

Ownership and decision-making

Research on space design in writing centers suggests that decisions should be based on the user experience and the types of activities that are expected to happen within the space (Sabatino). The furniture and space should be designed to promote the pedagogy of the center; the space should not dictate the pedagogy or limit the center's possibilities or growth. When space design puts the pedagogical practices at the forefront, it “highlights the importance of the programming that takes place within a space, using pedagogy as a guide from the outset rather than as an afterthought” (Carpenter et al. 314).

These recommendations stand in stark contrast to the experience of our respondents, who identified numerous issues of not having control over the design of their space. One respondent commented: “It’s NOT the Writing Center’s space. We can’t personalize it, make it reflect the quirky, student-centered culture our staff has cultivated.” Other participants made similar comments, noting their inability to decorate the walls, advertise services, arrange furniture, or even share food as a staff, due to library guidelines. Still others identified issues with not being able to move the furniture around or can only use furniture determined by another entity. For these participants, the lack of authority, control, or ownership over the center’s space in the library or its layout not only had a negative impact on the culture of the writing center, but also threatened the pedagogy of the space.

Another prevalent theme under lack of ownership included directors not having control over or the ability to advertise for the center. Participants noted the difficulties they have faced trying to get students to know where they are located or what services they offer due to the inability to advertise. As one participant explained, “we have zero control over the signage that would help increase the visibility of our Center.” Other participants noted challenges with getting approval to post flyers or appropriate signage. Since the space belonged to the library or the center was located within an open layout, directors reported struggling to find ways to promote their services. When the center is within an open space of the library without promotional advertising, visibility is diminished or non-existent; for instance, Kimberly Cuny et al. found the digital studio in their library practically disappeared without any obvious staff working there during non-operating hours. In addition to this practical concern, such challenges point to a bigger question: what are the implications if a center director lacks the ability to control or create their own messages? Both Peter Carino and Muriel Harris have argued for the importance of carefully considering the rhetorical implications of our institutional discourse, including everything from session reports to websites to flyers and the way that these documents can frame audience perceptions of writing centers and the work that takes place in them. Lacking the ability to create or shape their own messages may mean that centers and directors also lack an important way of influencing others’ perceptions of their work.

Due to ownership and lack of control over the space, centers also reported security issues. One participant described their need to “police the space.” Similarly, another participant shared: “we have no walls: often people wander in to sleep on our couch when we're in the middle [of] our day, and we have to politely ask them to move.” The perception and reputation of tutors and directors change when their role must shift from an academic assistance professional to a security guard figure who has to patrol the space or ask people to leave. Additionally, participants reported issues with not being able to maintain records, technology, or resources due to the open nature of their space and not having doors that locked. As a result, these open spaces contribute to a lack of legitimacy and make it harder for a center to maintain its professionalism without the appropriate tools to do so. Others noted that the center’s hours also became dictated by the library and building hours, meaning they could not always get into their space when they needed to.

While these participants were disturbed by this loss of ownership, some appeared unsure about whether this discomfort was justified. One participant prefaced their comments about loss of control of space with, “This seems trivial, but…” And it is understandable, that in the midst of a big institutional move, a director might want to avoid having extended conversations about the location of a table or refrigerator, to avoid engaging in what might seem like petty complaining. However, since space directly impacts the pedagogy of center work, its visibility, and people’s perceptions about the center, we believe directors need to voice their concerns. Furthermore, we agree with Douglas Walls et al. who argue that “space design is rarely—if ever—accidental, and as many scholars of space have indicated, spaces construct the social, that is, the positions and activities of the people in that space” (284). Others, including Jackie Grutsch McKinney and Kaidan McNamee and Michelle Miley have interrogated the metaphors of place (for example, “home”) used to characterize writing centers specifically, critiquing how these metaphorical conceptions of space can impact the individuals working in that physical space. Despite our participants’ tendency to minimize, we are reminded that decisions about space and design are not trivial and that they directly impact the tutoring, culture, and community the center cultivates.

Layout and design

In addition to having the power to make decisions about the design of the center’s space, layout and location within the library can impact the center’s pedagogy and culture. As Russell et. al state “spatial design should be pedagogically driven” (324). Writing centers are places where people come together to discuss reading, writing, and research. As a result, these spaces should help build a community of writers and should “foster and support relationships among students” (Sabatino 185). Spatial design can directly impact a center’s ability to build community, as Sara Littlejohn and Kimberly Cuny state,

Though there are several ways to accomplish community building, one essential piece of the puzzle is providing a shared space for consultants to gather, share stories, talk about theory and practice connections, and (more generally) find friendship and collegiality. Shared community among consultants contributes to the commitment that consultants feel to each other and to the center and its successful operation. (95)

Many of our participants, then, whose spaces are disjointed or open, found they lack the ability to bring people together or build community as a result. As one participant commented, their large, open-plan center resulted in a space that was “less intimate for building relationships with students (and faculty).” The mission for community and relationship building is at the heart of what writing centers strive to achieve when assisting writers, but, as our respondents report, centers struggle to build community and connections under the model where spaces are designed with an open layout, with no walls and with no dedicated space for the writing center.

Additionally, participants mentioned how the open access and layout design has impacted the perception of their services. As one participant stated, “some confusion about what is located where (because the space is primarily open).” This confusion could lead to writers not using the center’s services or, as previously mentioned, send the wrong message about the center’s services. Similarly, one participant characterized the lack of separate, dedicated space as contributing to a “perceived lack of legitimacy” on campus. This echoes Melissa Nicolas’ argument that “occupying a real physical space sends a message to the campus community that who or what inhabits that space is important enough to garner a piece of this limited resource since space connotes the power and the value attached to who or what occupies it” (para. 8). Therefore, without a dedicated space, the work is not visible and practically ceases to exist when the center is not open. As is evident in our participants’ own responses, the placement of a table, curtain, or chair can indeed impact the pedagogy of the center, tutoring, and ways students learn and compose. Furthermore, losing ownership of one’s space and having the ability to make important decisions about the center should not be a consequence of relocating to the library, but it appears, from our participants’ responses, that it all too often is. Recognizing that space is situational, we recommend that writing center space is flexible, separate, private with walls and dedicated space, and encourages community building.¹

Limitations

Through this study, we detailed the perceptions of writing center directors on the effects of their center’s location in their institution’s library. With a response of 104 participants, we consider our sample size significant. For comparison, the 2017 National Census on Writing’s Four Year Institution survey received data on writing center location from 477 institutions, 271 of whom reported that their institution’s writing center was located in a library; however, because we did not attempt to curate a sample of participants that was representative of all centers located in libraries, we cannot claim that this data is fully generalizable to all centers. Further, by including in our study centers that did not solely identify as writing centers (such as speech, communication, digital media centers) but not questioning participants about specific aspects of these differences, we further complicated any claims to generalization. Though the data and subsequent discussion are representative only of our participants, we believe the trends, themes, and questions we identified can serve as significant points for consideration for directors of centers who are anticipating a move to the library or negotiating the associated challenges, particularly as this study is the first of its kind to study the effects of center/library co-location.

An additional limitation that became clear as we began to analyze data was that in many cases, participants’ centers had moved to a library as a result of a consolidation into a learning commons, a student success center, or another sort of “one stop” model. As such, their comments on their centers’ move to a library were understandably in reaction to not just the move to a library, but to a broader institutional and physical centralization of student services. If we had included questions on our survey instrument that interrogated whether the centers in question were free standing or part of a one-stop service model, we would have been able to better determine how consolidation impacted participant responses.

Conclusion and Implications

The trends suggested by our survey have far-reaching implications; however, the diversity of responses we received was significant. While not comprising the majority of responses, some center directors did report forging strong collaborative partnerships with their library colleagues and found the new location of their center one that brings attention and credibility to its work. We discuss recommendations for establishing such positive collaborative relationships elsewhere (Herb and Sabatino). But, due to the overwhelming number of respondents who reported significant issues associated with their center’s move to the library from inadequate workspace to lack of authority/autonomy in making important decisions, we wanted to explore the impact of these problematic circumstances on the pedagogy of these centers—particularly so that those anticipating a relocation can think through the possible consequences. Additional questions remain about the full range of factors that may influence the divergent outcomes our participants reported. We suspect that in some cases, the location of the center in the library is less significant than the overall consolidation of tutoring services that has taken place. Thus, future research should also investigate various reporting lines and service models for writing centers, examining the different effects these have on the success of centers located in libraries. As our findings indicate, writing center/library co-location is a growing trend, so studying the characteristics and successes of various models will be particularly critical.

The results of our study showed that participants experienced challenges with space ranging from lack of privacy, silenced productive noise, and advertising to control, layout design, and security issues reminding us that space and location are not neutral concepts. Instead, a center’s physical positioning profoundly influences both outsider perceptions and, more importantly, the work done inside it. While relocating to a library may bring with it possibilities for developing new, collaborative relationships, it may also bring detrimental changes to a center’s pedagogy. Due to the significant effects on pedagogy and tutoring we observed from our participants’ reported challenges, we believe this decision should not be made lightly. If the decision to move a writing center into a library is made, the move should enhance, not impede, the center’s pedagogy, and all decisions should keep this end goal at the forefront. A center’s move to a library, then, must not be a top-down decision, but one that is genuinely supported by all stakeholders and one in which these stakeholders respect and value the voice and expertise of the center and its workers.

Notes

Since a thorough recommendation of spatial layout and design are beyond the scope of this research, we suggest readers review scholarship by Russell Carpenter, Carpenter et al., Kimberly Cuny et al., Leslie Hadfield et al., Karen J. Head and Rebecca E. Burnett, James Inman, Lindsay Sabatino, Douglas Walls et al., and Miranda Zammarelii and John Beebe, to name a few— all of which are in our works cited list.

Works Cited

Boquet, Elizabeth. Noise from the Writing Center. Utah State UP, 2002.

Brady, Laura, et al. “A Collaborative Approach to Information Literacy: First-Year Composition, Writing Center, and Library Partnerships at West Virginia University.” Composition Forum, vol. 19, 2009, compositionforum.com/issue/19/west-virginia.php.

Carino, Peter. “Reading Our Own Words: Rhetorical Analysis and the Institutional Discourse of Writing Centers.” Writing Center Research: Extending the Conversation, edited by Paula Gillespie et al., Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002, pp. 91-110.

Carpenter, Russell. "Negotiating the Spaces of Design in Multimodal Composition." Computers and Composition, vol. 33, 2014, pp. 68-78.

Carpenter, Russell, et al. “Studio Pedagogy: A Model for Collaboration, Innovation, and Space Design.” Cases on Higher Education Spaces, edited by Russell Carpenter, IGI Global, 2013, pp. 313-329.

Cooke, Rachel, and Carol Bledsoe. "Writing Centers and Libraries: One-stop Shopping for Better Term Papers." The Reference Librarian, vol. 49, no. 2, 2008, pp. 119-127.

Cuny, Kimberly M., et al. “The Digital Media Commons and the Digital Learning Center Collaborate: The Growing Pains of Creating a Sustainable Flexible Learning Space.” Sustainable Learning Spaces: Design, Infrastructure, and Technology, edited by Russell Carpenter, et al., Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State UP, 2015, https://ccdigitalpress.org/book/sustainable/s3/uncg/index.html.

Currie, Lea, and Michele Eodice. “Roots Entwined: Growing a Sustainable Collaboration.” Centers for Learning: Writing Centers and Libraries in Collaboration, edited by James Elmborg and Sheril Hook, American Library Association, 2005, pp. 42-60.

Elmborg, James. “Libraries and Writing Centers in Collaboration: A Basis in Theory.” Centers for learning: Writing centers and libraries in collaboration, edited by James Elmborg and Sheril Hook, American Library Association, 2005, pp. 1-20.

Elmborg, James K., and Sheril Hook. Centers for learning: Writing centers and libraries in collaboration. American Library Association, 2005.

Ferer, Elise. “Working Together: Library and Writing Center Collaboration.” Reference Services Review, vol. 40, no. 4, 2012, pp. 543-557.

Griffin, Jo Ann, et al. “Local Practices Institutional Positions: Results from the 2003-2004 WCRP national survey of Writing Centers.” The Writing Centers Research Project, 2004, http://coldfusion.louisville.edu/webs/a-s/wcrp/reports/analysis/WCRPSurvey03-04.html.

Hadfield, Leslie, et al. “An Ideal Writing Center: Re-imagining Space and Design.” The Center Will Hold: Critical Perspectives on Writing Center Scholarship, edited by Miachael A. Pemberton and Joyce Kinkead, Utah State UP, 2003, pp. 166-176.

Harris, Muriel. “Making Our Institutional Discourse Sticky: Suggestions for Effective Rhetoric.” The Writing Center Journal, vol 30, no 2, 2010, pp. 47-71.

Haviland, Carol Peterson, et al. “The Politics of Administrative and Physical Location.” The politics of writing centers, edited by Jane Nelson and Kathy Evertz, Boynton/Cook Heinemann, 2001, pp. 85-98.

Head, Karen J., and Rebecca E. Burnett. “Imagining It. Building It. Living It. A new model for flexible learning environments.” Sustainable Learning Spaces: Design, Infrastructure, and Technology, edited by Russell Carpenter et al., Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State UP, 2015, https://ccdigitalpress.org/book/sustainable/s1/head.burnett/living.html.

Herb, Maggie M. and Lindsay A. Sabatino. “Sharing Space and Finding Common Ground: A Practical Guide to Creating Effective Writing Center/Library Partnerships.” Writing Centers at the Center of Change, edited by Joe Essid and Brian McTague, Routledge, 2020, pp. 17-37.

Inman, James. “Designing Multiliteracy Centers: A Zoning Approach.” Multiliteracy Centers: Writing Center Work, New Media, and Multimodal Rhetoric, edited by David M. Sheridan and James Inman, Hampton Press, 2010, pp. 19-32.

Jackson, Holly A. “Collaborating for Student Success: An E-mail Survey of U.S. Libraries and Writing Centers.” CORE Scholar, 2016, https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ul_pub/178.

Littlejohn, Sara, and Kimberly Cuny. “Creating a Digital Support Center: Foregrounding Multiliteracy. Cases on Higher Education Spaces, edited by Russell Carpenter, IGI Global, 2013, pp. 87-106.

Mahaffy, Mardi. “Exploring Common Ground: US Writing Center/Library Collaboration.” New Library World, vol. 109, no. 3/4, 2008, pp. 173-181.

McKinney, Jackie Grutsch. "Leaving home sweet home: Towards critical readings of writing center spaces." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 25, no. 2, 2005, pp. 6-20.

McNamee, Kaidan, and Michelle Miley. "Writing center as homeplace (a site for radical resistance)." The Peer Review, vol. 1, no .2, 2017.

Mertens, Donna M. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods. 3rd ed., Sage, 2010.

Nadeau, Jean-Paul and Kristin Kennedy. “We’ve Got Friends in Textual Places: The Writing Center and the Campus Library.” The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 25, no.4, 2000, pp. 4-6.

“Four-year Institution Survey.” National Census of Writing, 2013, https://writingcensus.ucsd.edu/survey/4/year/2013.

“Four-year Institution Survey.” National Census of Writing, 2017. https://writingcensus.ucsd.edu/survey/4/year/2017.

Nicolas, Melissa. “The Politics of Writing Center as Location.” Academic Exchange Quarterly, vol. 8, no. 1, 2004, https://www.thefreelibrary.com/The+politics+of+writing+center+as+location.-a0116450594.

O'Kelly, Mary, et al. “Building a Peer-Learning Service for Students in an Academic Library.” portal: Libraries and the Academy, vol. 15, no. 1, 2015, pp. 163-182.

Ousley, Melissa. “The Luke Principle: Counting the Costs of Organizational Change for One-stop Service Models in Student Affairs. The College Student Affairs Journal, vol. 26, no. 1, 2006, pp. 45–63, eric.ed.gov/id=EJ902802

Sabatino, Lindsay, A. “Fostering Writing Studio Pedagogy in Space Designed for Digital Composing Practices.” Writing Studio Pedagogy: Space, Place, and Rhetoric in Collaborative Environments, edited by Matthew Kim and Russell Carpenter, Rowman & Littlefield, 2017, pp. 177-197.

Saldaña, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 2nd ed, Sage, 2013.

Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed, Sage, 1998.

Walls, Douglas M., et al. “Hacking Spaces: Place as Interface.” Computers and Composition, vol. 26, no. 4, 2009, pp. 269-287.

Zammarelli, Miranda and John Beebe. “A Physical Approach to the Writing Center: Spatial Analysis and Interface Design.” The Peer Review, vol. 3, no. 1, http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/a-physical-approach-to-the-writing-center-spatial-analysis-and-interface-design/.

Zauha, Janelle M. “Peering into the Writing Center: Information Literacy as a Collaborative Conversation.” Communications in Information Literacy, vol. 8, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1-6.

Appendix: Figures and Tables

Figure 1. Circle graph of institutional classification.

Figure 2. Circle graph of public/private status of institution.

Figure 3. Graph of reported years center has been in existence.

Figure 4. Graph of reported years center has been located in institution’s library.

Table 1. Top reasons centers/commons moved to the library

Table 2. Top benefits of centers/commons being located in a library

Table 3. Top benefits of centers/commons being located in a library