Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 18, No. 3 (2021)

Session Notes: Preliminary Results from a Cross-Institutional Survey

Christine Modey

University of Michigan

cmodey@umich.edu

Genie Giaimo

Middlebury College

ggiaimo@middlebury.edu

Joseph Cheatle

Iowa State University

jcheatle@iastate.edu

Abstract

In this article, we report on the results of a cross-institutional survey of sixty-one writing centers regarding their use of session notes, describing the nature of the forms used to record session notes, and also identifying and cataloging the various motivations and interests that seem to drive our field’s collection of session notes and the institutional and scholarly uses to which notes are put. Our project collected two types of data—survey data (about individual institutions’ use of session notes) and artifact data (blank session note forms and session note datasets). We begin by providing an overview of our methods and share our findings from responses to the survey and our analysis of the blank forms that institutions shared. We then discuss our findings, including implications and resources for developing and revising session notes as well as sample questions that indicate the range and the possibilities for session note use in writing center practice and research/assessment. Lastly, we argue for the importance of developing an open-access, evolving repository for this type of data in writing center studies. Following the publication of this article, we intend to make available the data we have collected and update it annually, providing new and increased opportunities for practitioners, scholars, and students to access and study this information.

Session notes are the forms that tutors (and sometimes clients, and sometimes both) complete at the end of a writing center session; these documents are also called “Client Report Forms” in the widely-used writing center appointment software, WCOnline. Session notes can fulfill many purposes, such as providing summative, descriptive, and/or reflective reports about individual tutorials. Though nearly every center creates them, session notes have not been the subject of extensive research. There were early debates about whether to share the documents internally or externally (Carino et al.; Pemberton; Crump; Jackson; Conway); and more recent research empirical approaches surveyed stakeholders about session notes’ utility or conducted discourse analysis on the notes themselves (Malenczyk; Bugdal et al.; Hall; Giaimo and Turner). But before we published our article “It’s All in the Notes: What Session Notes Can Tell Us About the Work of Writing Centers” (Giaimo et al.) based on analysis of a two-million word corpus of session notes from our four universities, studies had not analyzed sets of session notes from a multi-institutional perspective as a source of insight about our field, rather than a snapshot of the work of a particular writing center.

As Gofine argues, citing Jones and Harris, writing center practitioners and scholars have long pointed out that what one center produces, records, or chronicles is not the same for the next writing center; however, Gofine makes an argument for standardized assessment, particularly around data that is collected and reported for three common institutional and pedagogical reasons: to provide institutional accountability in the form of annual reports; to understand tutorials’ effect on students’ writing development; and to gauge writer satisfaction after tutorials (47). So while there might be institutional differences in writing centers—size, location, staff and student demographics, services, mission, etc.—writing centers do collect strikingly similar data for similar reasons. Nevertheless, acknowledging these similarities does not necessarily allow writing centers to learn from each other and replicate evidence-based practices. Rather, comparing and aggregating this data provides us new opportunities to think about the shared work of writing centers.

The research presented in this article is our initial attempt to analyze some preliminary cross-institutional data about session notes that we have collected on our way toward building a session note repository, supported by an IWCA research grant, which can be accessed by a broad group of practitioners and researchers. We are sharing the findings from the initial round of our survey in an attempt to initiate a field-wide opportunity to review and share data about session notes (forms and questions, datasets, and center metadata) that we hope can more robustly respond to questions that hitherto have seemed only answerable by “lore” (Gillespie). In this article, we describe the nature of the forms used to record session notes, and also identify and catalogue the various motivations and interests that seem to drive our field’s collection of session notes and the institutional and scholarly uses to which notes are put. Following the publication of this article, we intend to make available the data we have collected and update it annually, providing new and increased opportunities for practitioners, scholars, and students to access and study this information.

We begin by providing an overview of our methods and sharing our findings from responses to the survey and blank forms that institutions shared. We then discuss our findings, including implications and resources for developing and revising session notes as well as sample questions. Lastly, we point to the implications of our work and the importance of developing a repository for this type of data.

Methods

In preparation for the development of an open-access session note repository, we created and circulated the survey whose findings we report here. The survey gathered information about how (rather than why) writing centers conceive of, and use, session notes. Our survey collected two types of data—survey data (about individual institutions’ use of session notes) and artifact data (blank session note forms and session note datasets).

Because the student data from completed session note forms are aggregated and de-identified, and are currently collected for non-research purposes at many writing centers, the IRBs at our institutions determined that this project does not qualify as human subjects research and therefore no IRB approval was required. Blank session note forms/questions can be shared as these do not involve human subjects but are artifacts.

Study Participants

Writing Center Administrators (WCAs) from sixty-one institutions responded to the survey with fifty-two fully completing the survey, four indicating they did not use session notes (and therefore skipping the majority of the survey questions), and five filling out demographic questions—but few of the Likert scale questions. Fifty-seven respondents reported working with undergraduate students (among other groups) and forty-eight reported staffing with undergraduate tutors (among other groups). About a third of respondents (n=23) reported working at Liberal Arts institutions, fifteen at regional comprehensive institutions, eleven at research intensive universities, nine at two-year colleges, seven at Hispanic serving institutions, one at an historic black college and university, and eight indicating “other” (including schools with religious affiliation, secondary schools, technological institutes, and international universities). Some respondents reported two or more institutional types (e.g., liberal arts and regional comprehensive university), so the breakdown is not equal to the total number of respondents.

Forty-one respondents provided their blank session note form(s) and five respondents shared completed session note datasets. Those who shared their notes included a Hispanic-serving community college, a small national university, a research intensive university, and two small liberal arts colleges.

Survey

We developed a survey that included a range of demographic, open-ended, and Likert scale questions (Appendix C) that asked respondents about their engagement with session notes. Questions ranged from user-specific (open-ended response regarding session note training practices) to attitudinal (regarding session notes’ importance to tutor professional development). The survey also prompted respondents to share their blank session note forms and their session note datasets.

The survey was circulated through professional listservs, the International Writing Centers Association (IWCA) members’ listserv, the WCenter listserv, regional writing center listservs, and the Small Liberal Arts Colleges-Writing Program Administrators (SLAC WPA) listserv in the winter of 2020. Four schools reported not using session notes and, because of the way the survey was created, their surveys were largely blank. Additionally, another five respondents did not complete the survey so their responses were included only in the demographic responses and excluded from the Likert scale question results.

Because our study is an exploratory one that examines how our field engages with and thinks about session notes, our data analysis is descriptive, rather than correlative. At this moment, our field knows relatively little about the commonalities and differences in how and why writing centers use session notes. In the future, we hope to collect enough attitudinal, demographic, and artifact data for other researchers in our field to apply correlative statistics to the shared dataset. For now, however, descriptive statistics were compiled for the Likert scale questions and demographic data was aggregated from the survey. All numeric data was coded, analyzed, and formatted in Excel.

Session Note Forms

Respondents to our survey were invited to upload documents containing their blank session note forms in a variety of file types. The blank session notes were downloaded and examined individually and a list of distinct elements on the forms was developed (see Appendix D). New items were added to the list when items on a form didn’t clearly correspond to previously listed items. In the first pass-through of the forms, seventy-seven distinct items were identified, which covered most of the various forms’ components with some overlap and duplication. To simplify the lists and to make the forms more easily comparable, related sets of items were consolidated into single codes. For example, some forms allowed for both the writer and the tutor to indicate the focus of the session and the type of project that was brought in. In the refined set of items, two codes were created to indicate whether a particular form captured this kind of information about the appointment, whether from tutor or writer: “project info” and “appointment type.” In addition, many unique codes which applied to features appearing on only one session note form were eliminated in the refined list. For example, only one form inquired about writer gender and first-generation status; these items were not included in the final list. Notes about these unique features were instead included in a new “form description” field. After item consolidation, thirty-seven items remained.

While the submitted files capture the range of session note forms, analyzing and categorizing the variety of forms and file types poses challenges. For instance, a screenshot sometimes cuts off relevant information. Moreover, a screenshot does not capture options hidden in dropdown menus unless, as one thoughtful director did, the research participant video records the opening of each dropdown menu. Also, there is a fair amount of idiosyncrasy in how session notes are formatted and what is included in them, particularly at institutions that use “homegrown” systems. More than half of the respondents use WCOnline, which offers customizable session note form templates (called “client report forms” or CRFs). While CRFs can be downloaded from WCOnline with appointment data attached (such data often contains demographic information as well as information about the nature of the assignment, the name of the class, the type of appointment, and so forth), the WCOnline client report form alone does not provide this information. For this reason, in our analysis and discussion of the forms, we focus on the session note fields completed by tutors.

Study Limitations

As noted above, the overwhelming majority of survey respondents (93%) currently use session notes in their writing centers. And, as we discuss below, roughly a third of respondents currently engage in research and assessment of these documents. Therefore, this study skews towards practitioners who currently use session notes in their writing centers and who robustly—though unevenly—engage in research about these documents. Additionally, the majority of respondents reported working at liberal arts institutions with more limited survey engagement from people at two-year colleges, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and Hispanic-Serving Institutions, though we did have respondents from all of these institutional types in additional to research intensive institutions, etc. (see above for responses by institutional types). Rather than providing an accurate representation of the field, then, with regards to uncovering who does and does not use session notes, our findings provide a more detailed—and limited—snapshot of our field’s engagement with session notes.

Results

Survey Findings

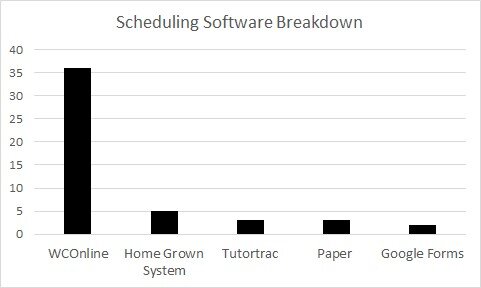

From our survey’s respondents, we notice that those respondents who report engagement with these forms do so robustly. These institutions also share commonalities in how they collect session notes and other writing center data and records (Table 1 & Figure 1). Of the sixty-one respondents to the survey, the majority (93%) report utilizing session notes (Table 1). The majority (n=36), or 59%, report using WCOnline as their scheduling software, with Tutortrac, homegrown systems, Google forms, and paper evenly spread out among institutions (two to three each) and the “Other” category comprising the rest of the responses (n=12) (Figure 1).

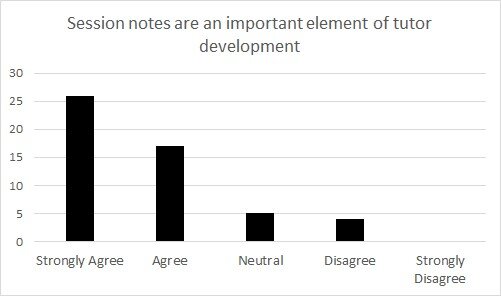

Survey respondents responded affirmatively to many practices regarding session notes. For example, the majority (83%) provide session note training to their staff and roughly the same number (80%) share their session notes with populations within and/or outside of the writing center (Table 1). Respondents also largely believe that session notes are an important part of tutor training and professional development (Figure 3), with 75% of respondents who use session notes in their writing center (n=43) responding very favorably or favorably to the statement that session notes are an important element of tutor development.

While most respondents responded positively to questions about the administrative elements of session notes, such as engaging in tutor training, or believing that session notes support tutor development, the majority (64%) do not conduct research and/or assessment on their notes (Table 1). Of the minority (36%) of respondents who conduct research and/or assessment, fewer still (32%) described their research projects. Those who did reported engaging in a range of projects from informal review of notes to identify tone and emergent patterns in tutor practices, to comparing and correlating session notes to intake forms, to conducting discourse analysis on session notes. Of course, these approaches to session note research need not be mutually exclusive: many respondents reported trying to achieve multiple goals through their assessment of session notes while others reported struggling to find the time to conduct such research.

While only about a third of respondents currently conduct research on their session notes, the majority of respondents (59%) have very strong or strong interest in doing this kind of work (Figure 4). A similar cohort of respondents (57%) also responded very favorably or favorably to joining a multi-institutional research project, such as the one the authors of this paper are conducting (Figure 5).

Session Note Findings

The session note forms themselves range from very basic (for example, writer name, tutor name, and focus of the session) to complex (for example, requiring three screens to display, and including thirty-eight separate items). Fifteen of the forms were paper, while twenty-six were electronic. Most forms appear to be completed by the tutor after the session, although some have parts of the form completed by the writer before or after the session, a couple are clearly intended to be completed by the tutor and the writer together, and at least one form appears to be completed entirely by the writer, with the tutor simply signing off at the bottom.

Apart from collecting personal information, such as writer and tutor names, session note forms most frequently collect information about the focus of the session. For assessment and institutional accountability purposes, respondents indicated a strong interest in knowing what people bring to the writing center. For instance, twenty-two of the session note forms include some kind of open text field for “type of assignment” or “type of project,” while six forms include a checklist (two forms include both an open text box and a checklist). Additionally, twenty-six of the forty-one forms submitted include a checklist of items for the tutor focus. These checklists range from a short list of five items only, to an elaborate list of twenty-seven items divided into six categories such as “stage of the writing process,” “rhetorical choices,” and “language, grammar, usage, and mechanics.” About half of the forms (n=22) use open text boxes with minimal guidance (such as “describe the session” or “summarize the session”) to collect information about what happened in the session, while nineteen provide open text fields with more directive questions asking the tutor to identify areas on which the writer needs additional work, areas in which the tutor saw improvement, the strengths and weaknesses of the session, an assessment of the quality of the paper, the tutoring strategies used, and so forth. In all, thirty-nine of the forty-one session note forms include at least one open text box to collect information about the session, with a total number of open text boxes on any given form ranging from one to four.

In addition to these commonalities, there are notable shared absences among the forms as well. For example, the forms shared by respondents do not pay special attention to multilingual issues; only three ask about the writer’s first or home language and only two provide a specific “ESL issues” focus checklist of some sort. One session note form allows the tutor to record whether it had been a multilingual session - in other words, whether multiple languages were spoken by the writer and tutor in the session itself. Given that at many writing centers multilingual writers make up a substantial number of the total appointments, it is perhaps surprising that multilingual issues are not more deeply examined via session note forms.

Most respondents’ session notes record no information about tutoring strategies or about referrals to outside resources. Only one form explicitly asks about tutoring strategies, while four ask about use of or referral to additional resources. Tutoring strategies no doubt get recorded in other ways (for instance in open text responses) but the fact that strategies are not explicitly called out may suggest that many directors think of session note forms as a way to learn about the writer and the session, not the tutor. More session note forms record information about resources used or referrals made than about tutoring strategies employed, but these are still a small proportion of the overall number of forms submitted.

Only three respondents’ forms record whether the tutor recommended a follow up session for the writer, which is notable if we conceptualize writing centers as places of process-oriented instruction where a writer might make a sequence of appointments, perhaps to work on different aspects of a writing project. From a different perspective, writing centers eager to boost their numbers and demonstrate their utility to administrators might encourage tutors to suggest follow-up appointments. It is worth noting that WCOnline, the appointment system used by more than half of the writing centers surveyed, allows automatic tracking of return visits. Eight forms allowed a tutor or writer to indicate directly that they had previously visited the writing center. Ultimately, however, few centers appear to use the notes explicitly to track “continuity of care,” including considering when tutors cross-refer students and/or encourage them to return to the writing center.

A Note on Respondent Outliers

Although many session notes shared common features, some forms or questions were so unusual that they are worth mentioning here. Writing centers are very much creatures of their institutions, driven by local population needs and institutional interests. As a result, there is a lot of variation within the session note forms, both in the complexity of the session note forms and also in kinds of information they collect.

Six forms, for example, provide opportunities for the tutor to evaluate the session while three others ask the tutor to comment directly on the writer’s behavior; for instance, whether they were prepared for the session and engaged in the tutoring process. While the evaluation questions can raise the question of whether the tutor thought their work was effective, other questions seem to serve a regulatory purpose, monitoring student behavior, perhaps with the intention of reporting that behavior to the faculty member or including it as an aspect of the student’s evaluation in a writing course. One form, for instance, provided three Likert-scale questions about how often a writer used a laptop or writing utensil, took notes, and asked questions. Given the form’s overall orientation toward the student, these questions may also have the effect of communicating expectations about student engagement.

In addition, a few forms solicit specific demographic information about student writers that reflects ongoing conversations in our field and in our institutions about how well we serve writers from a variety of backgrounds (see, for example, Salem; Denny et al.). For instance, one form asks about a writer’s first and additional languages as well as asks the writer to identify their gender by providing a space for self-defined gender (with the option to decline to answer the question). Another form provides opportunities for the writer to disclose whether they are beyond traditional college age (over twenty-four years) and whether they are the first in their family to attend college, as well as their first language.

While most session note forms are clearly oriented to the tutor and the writing center, a few recruit the writer to reflect on the session or encourage the writer and the tutor to work together to summarize the session and identify next steps. One, for instance, in addition to asking the tutor to reflect on the session also asks the writer to identify areas in which they made progress during the session and helpful strategies or advice provided by the tutor, and to rate the overall effectiveness of the session and explain their rating. Another form, written in the first-person plural, asks the tutor and writer to identify areas worked on and to prioritize next steps. Yet another form asks the writer to identify up to three specific areas they worked on and also to identify corresponding next steps and strategies that might be transferable to future writing assignments. On this form, the tutor provides only a signature.

Discussion

As noted in the results, the majority of survey respondents indicated fairly robust engagement with session notes in their centers, insofar as the majority of centers use session notes, train their tutors to fill out session notes, and share their notes with internal and/or external audiences. They also responded with high agreement that session notes are an important element of tutor professional development.

However, while 70 - 90% of institutions that responded to the survey reported in-depth administrative engagement with session notes, only 36% of respondents currently conduct research on session notes (Table 1) while 59% of respondents are interested in engaging in such research (Figure 4). Additionally, while over forty institutions shared their blank session note forms with the researchers, only five institutions shared their actual notes. This suggests that, while there is deep and abiding interest in session notes among this cohort of institutional respondents, research and assessment are more difficult to engage with than training and other elements related to the administrative and day-to-day use of session notes in writing center work. Considering the dearth of research on session notes—even the praxis oriented topics of session note tutor training and professional development via session notes—the researchers note that there are some barriers (which we posit might be related to labor and compensation concerns) to creating multi-institutional and large-scale research and assessment projects on session notes. So, while our survey respondents report incredibly thoughtful praxis-oriented engagement with session notes, there appear to be opportunities for translating practice into research and assessment practices that have impact beyond individual centers.

After analyzing the blank forms/artifacts that centers provided, we argue that the number of open text fields regarding session focus is a tantalizing opportunity for research—and also a challenge. On the one hand, these open text fields provide abundant linguistic data that can be analyzed using corpus techniques. This strategy seems useful especially for the fields that ask tutors, broadly, to “describe the session” or something similar. Analyzing such data will reveal much about the language tutors use to describe their work in a wide variety of writing center settings. On the other hand, using corpus analysis techniques on the open text generated in response to the narrower questions may create some strange irregularities in the data, especially with a relatively small corpus.

Moreover, for any individual writing center director or coordinator, a survey of the session note forms offers food for thought in terms of their own center and their own tutor training process. Session note forms, as indicated above, can take on various perspectives: some administrative, some reflective, some evaluative. The questions they ask, the emphasis they place, shapes the uses to which they can be put, and their limitations. Writing center directors looking to update their session note form could do worse than reflect on their own goals for those forms—do they want to use them to communicate within the center? To demonstrate efficacy for faculty and administrators? To promote effective writing and revision processes? To improve tutor performance? To deepen tutor reflective practice? —and then to examine the variety of questions their colleagues are asking, in various unique writing center settings around the world, and identify some that, if used, would help them to revise their forms to align with their centers’ priorities.

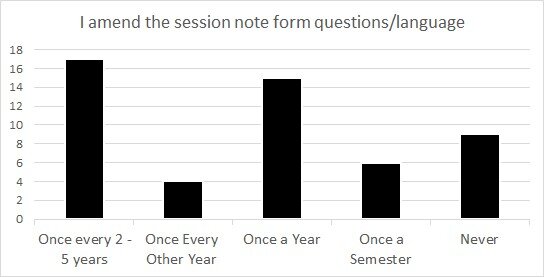

A final note indicates how our field might be moving into more standardized practice due to shared technology platforms: the researchers found that the majority of institutions (59%) use WCOnline for scheduling, record keeping, and most pertinent to this study, session notes (Figure 1). Nearly all of those who submitted session note forms from the WCOnline platform adapted the template in some way; nevertheless, it is clear that the WCOnline template influences the structure and content of session notes. Similarly, about half of the respondents reported inheriting their session note forms and language from their predecessors (Table 1). Forms themselves, however, are amended over a variety of time periods with 33% amending their forms every two to five years and 17% never amending their forms, with a set of other revision periods (every other year, once a year, and one a semester) comprising the rest of the responses (Figure 2). Therefore, while there is more standardization in how these forms are collected, there is less continuity in how often they are revised and how they are developed in the first place. This suggests we need to do more, as a field, to implement best and potentially standard practices regarding these valuable administrative and scholarly artifacts of tutor and writer work.

The extensive use of WCOnline by survey respondents points to an opportunity to develop aggregable session note data. Use of a “standard” commercial platform can be good insofar as it allows busy directors to immediately implement data collection and tether many of the commonly collected records around the work of writing centers in a single place. In addition, the widespread use of WCOnline likely affects how session notes are developed, disseminated, and used across many writing centers in unforeseen and hitherto under-examined ways. WCOnline provides a template for session note form questions, which the researchers observed were used unaltered by only two of the twenty-three respondents who shared their session note forms from WCOnline. Nevertheless, most adaptations to the WCOnline template were minimal – such as the addition of a checklist for the focus of the session, customized language for an open text box, or the addition of another text box.

We posit that direct use or minimal adaptation of the WCOnline template might contribute to a flattening of both the language that session notes contain (i.e., the kinds of questions and prompts it asks of tutors) but, also, because of how the program makes session notes accessible (i.e., they are more easily accessed by writer rather than individual tutor), it also limits engagement with session notes to largely administrative functions. In other words, because session notes are tethered primarily to sessions and unique clients, and it is more complicated and time intensive for tutors to access their own aggregated notes, a culture around session notes as largely administrative, rather than research or assessment focused, might be developing in our field. So, while WCOnline offers convenience for time strapped WCAs, it also might be contributing to a homogenization in our record keeping practices that shapes and drives why we collect these artifacts in the first place.

Implications and Resources for Developing and Revising Session Notes

For WCAs who are interested in revising their session notes, as well as those who seek resources to support tutor training on completing session notes, we reviewed hundreds of session note questions and observed that the most effective notes were the ones that have clear goals in mind. We identified three key considerations for session notes, including audience(s) of the form, author(s) of the form, and goal(s) of the session note form. For each consideration we explain why it is important, identify variables that may affect it, and provide guidance on implementation.

I. Who is the audience of the session note form?

Session notes can have multiple audiences:

writer

tutor

faculty members

writing center administrators

college or university administrators

Each audience has different concerns and interests and these must be taken into consideration when developing session note forms and when training tutors on their completion.

Implementation: For those WCAs developing questions for session notes, it might make sense to chart the audience(s) for each specific question before determining whether or not the question is effective. For those generating new questions, mapping out the audiences by the number of questions can help the WCA to get a clearer sense of what specific functions they want their questions to perform. For example, if you want tutors to reflect more carefully on their tutoring practices, you will want to explicitly identify tutors as the audience for any questions on tutoring practice.

II. Who completes the session note form?

Most session note forms were completed by tutors; however, forms may also be completed solely by the writer or by the tutor and the writer in collaboration with one another. In developing or revising session note questions, then, it makes sense to consider who is completing the form, as the goals of the question vary depending on the author(s) of the form.

Implementation: If the tutor and the writer complete the report form, then it should include both of their viewpoints. Questions should aim to capture whether or not the session was collaborative and how engagement/authority were negotiated in the consultation. However, both tutor and writer may not feel they can be honest about the consultation; therefore, a separate section where the tutor and the writer can respond individually may also be warranted. A form that is meant to be shared with faculty members should look different from a form that is intended solely for writing center administrators and tutors.

III. What is your goal for specific questions in the session note form?

We observed that most questions on session note forms fell into one of the following categories: description/summary, evaluation, reflection, or assessment/research. Single questions may address multiple goals, but it is more typical for most questions to fall into one of the first three distinct categories, while all questions are potentially useful in research and assessment.

Implementation: Pedagogical and administrative goals for each center vary, as do the kinds of research and assessment, so amend specific questions to address your center’s needs. Research goals might include understanding whether tutors and writers differ in their articulation of outcomes for the session, or it might be to analyze what kinds of rhetorical moves tutors make when describing their tutoring practice. In addition, alignment of different data collection forms—such as session notes with client intake forms and student satisfaction forms—also helps in developing robust assessment projects.

Sample Questions

Question content and structure profoundly affect the responses tutors generate. While open-ended questions asking the tutor to summarize the session offer endless opportunities for reflection and response (see, for example, Hall, pp. 87-89), more targeted questions can better address research or pedagogical goals. For example, if a WCA is interested in tutors’ inclusive practices, it makes sense to incorporate key terms such as “inclusion,” or “anti-racist,” in the question. Of course, for tutors to engage thoughtfully with this kind of a question, training also needs to be provided. As WCAs develop their questions, it is important to determine if tutors/writers have the necessary vocabulary (and knowledge) to respond in thoughtful and specific ways.

Each question in a session note form serves a different purpose. To that end, we provide two lists of questions—the first (Table 2) provides a set of sample questions that reflect some of the most common questions asked, and the second (Table 3) provides a set of more unusual questions that offer alternative ways to prompt tutor and writer reflection.

Some of the unusual questions are situated in the local context of a writing center and reference specific priorities or training initiatives; considering a center’s training initiatives, values, and practices is a good way to help to develop questions that may help an administrator evaluate the effectiveness of a session in light of a center’s goals.

Conclusion

Session notes are a critical component of writing center consultations, yet they are underused in institutional research and assessment. While some centers attempt to maximize their usage and effectiveness, others may not revisit their session notes regularly or may use outdated session note forms. Though we do not advocate that every writing center turn its session notes into materials for research or assessment, we do argue that writing centers approach their session notes with purpose.

Moreover, we believe that session notes are a rich source of data about how the theories and commitments of our field (to inclusive and anti-racist practices, for instance, or to supporting disciplinary literacies and writing development, or to better understanding the labor of writing tutors) are enacted in writing center sessions. Like writing center observations, session notes provide direct insight into the experience of writing center work from the perspective of the worker. While collecting detailed demographic information about writers provides insight about whom we serve, studying session notes can reveal much about whether and how our shared theories about writing center work are put into practice. Cross-institutional research on session notes, in particular, can aid in this endeavor.

Building on our work in this article, we are developing a repository to house session notes as well as the metadata that we are collecting from individual institutions regarding their engagement with session notes. We are responding to Joyce Kinkead’s work that calls for making writing center work more visible and repositories to house work documents are needed for future researchers (10, 15). Brad Peters, likewise, argues for the importance of documents as a way for writing centers to show “how socialization patterns have come to define the writing center’s institutional position in the past, how they presently define it, and how they might help to redefine it” (104). Peters focuses on the power of narratives to “help writing center directors identify and understand local strategies that reflect and lead to future, rhetorically effective decision making and problem solving” (104). Both Kinkead and Peters recognize the value of creating, using, and storing documents as central to writing center research. Readers interested in sharing their session note forms and texts in the repository are invited to complete the survey: http://middlebury.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_3abDYMB4ewHthSR.

We want to note that what we advocate for, and are creating, is a repository and not an archive. The “Archives and Records Management Resources” page of the National Archives helps explain why archives don’t necessarily perform the function of a document repository: namely, archives are organizational records that are considered “permanently valuable” and are typically deposited “when the organization that created them no longer needs them in the course of business.” By contrast, the evolving document repository we propose will be built through the contributions of writing centers administrators and used in their day-to-day work. Administrators and practitioners alike can find examples of session note forms, learn how session notes are used by other centers, and conduct research on session notes. We plan to continue our research into session notes and also to broaden our scope of research to consider other documents (such as registration forms, intake forms, and client surveys) that we frequently use in writing centers but don’t always use effectively. Our work here, and the future data repository, bring together practitioners and researchers while serving practical purposes and providing important insights to the field of writing center studies.

WORKS CITED

Archives and Records Management Resources. National Archives, 15 August 2016, https://www.archives.gov/research/alic/reference/archives-resources. Accessed 8 July 2019.

Bugdal, Melissa, et al. “Summing Up the Session: A Study of Student, Faculty, and Tutor Attitudes Toward Tutor Notes .” Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 3, 2016, pp. 13–36.

Carino, Peter, et al. “Empowering a Writing Center: The Faculty Meets the Tutors.” Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 16, no. 2, 1991, pp. 1-5.

Conway, Glenda. “Reporting Writing Center Sessions to Faculty: Pedagogical and Ethical Considerations.” Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 22, no. 8, 1998, pp. 9–12.

Crump, Eric. “Voices from the net: Sharing records: Student Confidentiality and Faculty Relations.” Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 18, no. 2, 1993, pp. 8–9.

Denny, Harry, et al. “‘Tell Me Exactly What It Was That I Was Doing That Was so Bad’: Understanding the Needs and Expectations of Working-Class Students in Writing Centers.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 37, no. 1, 2018, pp. 67–100. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26537363. Accessed 13 Aug. 2020.

Giaimo, Genie, et al. “It’s All in the Notes: What Session Notes can tell us About the Work of Writing Centers.” The Journal of Writing Analytics, vol. 2, 2018, pp. 225– 256.

Giaimo, Genie, and Samantha Turner. “Session Notes as a Professionalization Tool for Writing Center Staff: Conducting Discourse Analysis to Determine Training Efficacy and Tutor Growth.” Journal of Writing, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 131-162.

Gillespie, Paula. “Beyond the House of Lore: WCenter as Research Site.” Writing Center Research: Extending the Conversation. Routledge, 2002, pp. 39-51.

Gofine, Miriam. “How are we Doing? A Review of Assessments Within Writing Centers.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 32, no. 1, 2012, pp. 39-49.

Hall, R. Mark. Around the Texts of Writing Center Work: An Inquiry-Based Approach to Tutor Education. Utah State University Press, 2017.

Harris, Muriel. “The Concept of a Writing Center.” National Writing Project. 1988, https://archive.nwp.org/cs/public/download/nwp_file/15402/Writing_Center_Concept.pdf?x-r=pcfile_d. Accessed 8 July 2019.

Jackson, Kim. “Beyond Record-Keeping: Session Reports and Tutor Education. Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 20, no. 6, 1996, pp. 11–13.

Jones, Casey. “The Relationship Between Writing Centers and Improvement in Writing Ability: An Assessment of the Literature.” Education, vol. 122, no. 1, 2001.

Kinkead, Joyce. “The Writing Center Director as Archivist: The Documentation Imperative.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 41, no. 9-10, 2017, pp. 10-17.

Malenczyk, Rita. “‘I Thought I'd Put That in to Amuse You’: Tutor Reports as Organizational Narrative.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 33, 2013, pp. 74–95.

Pemberton, Michael. “Writing Center Ethics: Sharers and Seclusionists.” Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 20, no. 3, 1995, pp. 13-14.

Peters, Brad. “Documentation Strategies and the Institutional Socialization of Writing Centers.” The Writing Center Director’s Resource Book, edited by Christina Murphy and Byron Stay. Routledge, 2012, pp. 103-113.

Salem, Lori. “Decisions...Decisions: Who Chooses to Use the Writing Center and Why.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, 2016, pp. 147-171.

Appendix A: Tables

Table 1: Responses to questions about how session notes are used by individual institutions broken down by number of respondents and percentage of responses to questions.

Table 2: Table showing sample questions and directions that are commonly used in session notes across writing centers.

Table 3: Table showing sample questions and directions that are less commonly used in session notes across writing centers.

Appendix B: Figures

Figure 1: Breakdown of the scheduling and note taking methods used by individual writing centers.

Figure 2: Breakdown of individual writing centers and how often they amend the language within session note forms.

Figure 3: Figure showing breakdown of respondents by their agreement to statement that session notes are an important element of tutor development.

Figure 4: Figure showing respondents’ desire to conduct research or assessment on session notes with the majority (n= 36) indicating very strong or strong agreement.

Figure 5: Figure showing respondents’ desire to join a multi institutional research project on session notes, with the majority (n= 35) indicating very strong or strong agreement.

Appendix C: Session Note Data and Information Collection Survey

As part of an IWCA-funded research project, we are creating a shared repository for writing center session notes and the forms that individual writing centers use. This repository will allow writing center administrators to engage with a large and multi-institutional set of data that includes both completed session note forms and the attendant questions that these forms ask. These data are useful for conducting assessment, for pedagogical purposes, and for re-envisioning individual center's session note practices.

Because these data are aggregated and de-identified, and are currently collected for non-research purposes at many writing centers, our IRBs said that this project does not qualify as human subjects research and therefore no IRB approval is required. Indeed, BLANK session note forms/questions can be shared, as these do not involve human subjects but are artifacts. HOWEVER, please check with your individual IRBs before sharing completed session note forms. While we have been given a confirmed response that these data do not fall under human subjects research from our institutions, this may not be the case at other institutions. So, please share this information, as well as the Qualtrics survey with your IRBs before participating.

For questions, please contact the researchers:

Genie Giaimo (Middlebury College): ggiaimo@middlebury.edu

Christine Modey (University of Michigan): cmodey@umich.edu

Joseph Cheatle (Iowa State University): jcheatle@iastate.edu

Demographic and Institutional Questions

Q1. Title of Institution and Name of Writing Center:

Q2. Primary Contact name:

Q3. Primary Contact Email Address:

Q4. Primary Contact Phone Number:

Q5. Secondary Contact Name:

Q6. Secondary Contact Phone Number:

Q7. Writing Center Website Link:

Q8. Institutional Type (check all that apply):

● Two-Year College

● Four-Year Liberal Arts College

● Regional/comprehensive university with Master's or specialist degree programs

● Research intensive or extensive (Research I) university

● Historically black college/university

● Tribal College

● Hispanic Serving Institution

● Other

Q9. If Other, can you please list your institutional type?

Q10. Client Population Served (check all that apply):

● Undergraduate Students

● Graduate Students

● Professional Students (Medical School, Law School, etc.)

● Faculty/Staff

● Community members

● High School/Secondary School Students

● Alumni

● Other

Q11. What kinds of tutors/consultants do you employ in your writing center? (check all that apply)

● Professional Staff Tutors

● Faculty Tutors

● Graduate Student Tutors

● Undergraduate Student Tutors

● Other

Q12. What kind of scheduling system do you use in your writing center?

● WCOnline

● Home grown online system

● Tutor Track

● Google Forms

● Paper forms

● Other

Session note/client report form use

Q13. Do you use session notes/client report forms (summative notes describing each writing center session) in your writing center?

● Yes

● No

Condition: If No is selected. Skip To: End of Survey.

Q14. Do you share your session notes internally (with your staff) or externally (outside of the center)?

● Yes, we share our session notes

● No, we do not share our session notes

Condition: If No is selected. Skip To: Do you conduct training on session notes?

Q15. If you share your session notes/Client Report Forms externally (outside your center), whom do you share them with? (check all that apply)

● Students/clients

● Instructors

● Other external stakeholders (Deans, RAs, Counseling etc.)

● By student/client request

● Other

Q16. If you share your session notes/client report forms internally (with your staff), how do you do this? (check all that apply)

● Tutors can review previous notes from other sessions

● We share representative notes among tutors

● The Director/Administrator reviews notes and reports out findings to staff

● Other

Q17. Do you conduct training on session note completion for tutors?

● Yes

● No

Q18. If you conduct training on session note completion for tutors, please describe the training and its aims:

Q19. I inherited my session note form/questions from a previous administrator

● Yes

● No

Q20. I amend the session note form questions/language:

● Once a semester

● Once a year

● Once every other year

● Once every 2 - 5 years

● Never

Session note research and assessment

Please identify to what extent you agree or disagree with the following statement about session note use in your center:

Q21. Though session notes are used in my writing center, I have not examined the process closely.

Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

Q22. I currently do research/assessment on my session notes

● Yes

● No

Condition: If No is selected. Skip To: I would like to do research or assessment on session notes.

Q23. Please describe your research/assessment on session notes.

Q24. I would like to do research or assessment with session notes.

● Strongly agree

● Agree

● Somewhat agree

● Neither agree nor disagree

● Somewhat disagree

Q25. Session notes are an important element of tutor development.

● Strongly agree

● Agree

● Somewhat agree

● Neither agree nor disagree

● Somewhat disagree

Q26. I am unsure of how to use session notes effectively in research/assessment.

● Strongly agree

● Agree

● Somewhat agree

● Neither agree nor disagree

● Somewhat disagree

Q27. I would like to join a multi-institutional research project on session notes. If so, we would love to contact you!

● Definitely yes

● Probably yes

● Might or might not

● Probably not

● Definitely not

Institutional data collection

Q28. For our grant, we are collecting artifacts related to the practice of using session notes. Here, please attach a BLANK session note form, as a screen shot, or share the questions on your session note form in a .doc or .docx file.

Q29. If you have a second form only, please attach a BLANK session note form, as a screen shot, or share the questions on your session note form in a .doc or .docx file.

Q30. I certify that I have the authority to upload these writing center session notes.

● Yes

● No

Q31. We are also collecting session notes from writing centers in Higher Education Institutions. Attach a single file (.csv or .xls) with all session notes from your institution. All identifying information must be redacted prior to upload.

Q32. I certify that I have redacted identifying information in these writing center session notes.

● Yes

● No

Appendix D: Codes