What Do Students Learn and Expect to Learn From Consultants and Faculty in Courses Supported by Course-embedded Consultants?

Julia Bleakney

Elon University

jbleakney@elon.edu

Julia Herman

Elon University

jherman9@elon.edu

Paula Rosinski

Elon University

prosinski@elon.edu

Abstract

This study presents the results of our analysis of a subset of student survey data, collected over seven years of Elon University’s course-embedded consultant (CEC) program. Our analysis aims to understand how students in courses with an assigned CEC perceive to benefit from working with their CEC in tandem with the guidance they receive from the instructor. Since the synergy between the CEC and instructor is crucial to the success of the program, we hoped to see that students were learning complimentary things about writing from their CEC and their instructor. We analyzed students’ responses to survey questions about their learning from the CEC and the instructor by individual course, seeking to pinpoint how students’ expectations for learning at the beginning of the course align with or compare to their perceived learning at the end of the course. Many previous studies have sought to determine the benefits to students of CEC programs, and our study seeks to embrace the variation across individual courses and to look at learning in the course more holistically. Finally, our analysis helps us understand what we might do differently to manage students’ expectations and enhance their perceptions of learning in the course.

Introduction

For as long as course-embedded writing consultant (CEC) programs have been around, there have been attempts to explain how to effectively create them, which features such programs need in order to be successful, and how to determine their success or effectiveness. Bradley Hughes and Emily Hall detail the positive experiences that faculty have when working with a CEC who is well-trained to support students in the course. A previous study to which we contributed (Bleakney et al.) presents faculty’s and CECs’ perspectives on the positive benefits of working with a CEC: both faculty and CECs observed students benefiting from a conversation on their writing and on attention to the writing process. Other studies (Titus et al; Glotfelter et al; Carpenter and Whiddon; Dvorak et al. [2020]; Zawacki) describe the benefits to students of working with a CEC, from the perspective of the CEC or the faculty. However, there are some studies that look at students’ self-reported learning. In “Getting the Writing Center into FYC Classrooms,” Kevin Dvorak, Shanti Bruce, and Claire Lutkewitte (2012) asked students in an end-of-semester survey to report on what they had learned from their CEC. Completed by 113 of 125 students, the students’ most frequent response was that they “learned the value of working with another person on their writing,” followed by learning “specific writing skills,” followed by “the value of revising their writing.” More recently, Laura Miller’s mixed methods research on mindset and CECs uses an experimental model (with a control group of students without a CEC), a pre- and post-survey, and analysis of students’ writing from the course, and found that students who worked with a CEC demonstrated “dramatic mindset changes” (114). A throughline in these studies is the assumption that CEC programs are absolutely worth the time, effort, and cost as there are clear benefits to faculty, CECs, and students.

These benefits are apparent in the scholarship regardless of whether the CEC supports first-year writing (FYW) courses or more advanced or discipline-specific writing courses. For FYW support, some CEC programs make a CEC available for every course; other programs are more selective or limited. For advanced or discipline-specific writing support, CEC programs typically recruit or select interested instructors with whom to pair a CEC. In some programs, CECs attend the class and provide support during class time; in other programs CECs provide consulting support outside of class time. Some programs seek to provide consistency of support across courses; but other programs–such as the one we discuss in this article–permit a great deal of variation and flexibility, as individual CECs, partnered with different courses in the disciplines, provide writing support tailored to each individual course and instructor.

While this flexibility helps meet students’ specific needs within different disciplines, and allows for academic freedom prized on many campuses, the variations in students, consultants, instructors, and course contexts makes assessing the program challenging. In our context, we have been collecting student survey data on our CEC program since the program’s inception in 2016. Students are asked to comment on their expected learning (in a survey administered at the start of the term) and what they perceived to have learned (in a survey administered at the end of the term). As we determined how to make sense of the data, we decided to embrace this variation, rather than attempt to control for it. Thus, our analysis aims to understand how students in courses with an assigned CEC perceive to benefit, holistically, from working with their CEC in tandem with the guidance they receive from the instructor. Since the synergy between the CEC and instructor is crucial to the success of the program, we might expect to see in our analysis that students are learning complementary things about writing from their CEC and their instructor.

To understand how our program is working, we analyzed students’ responses to survey questions about their learning from the CEC and the instructor by individual course, seeking to pinpoint how students’ expectations for learning at the beginning of the course compare to their perceived learning at the end of the course. Building on our previous study of CECs’ and professors’ perspectives (see Bleakney et al.), this current study of student feedback adds a layer of understanding to our programmatic assessment, from the students’ perspectives. The value of looking at students’ feedback based on individual courses and regarding their experiences with both CECs and faculty is that it allows us to not only embrace variation by discipline and to look at learning in the course more holistically but also to understand what we might do differently to manage students’ expectations and enhance their perceptions of learning in the course. In our analysis of the survey responses, we found a wide variety of student expectations for learning, including some high expectations that went beyond what might be covered in the course, and we found less evidence of students’ perceptions of learning especially compared to their (high) expectations. Students expected to learn different things from their CEC and their professor, and though there was little evidence of perceptions of learning, some students did perceive learning things about writing from their professor. This finding—that students’ perceived they learned about writing from their professors but not their CECs—might seem to run contrary to the goals of CEC programs and published research, and so deserves some interrogation. After presenting our methods and findings, this article ends with some recommendations for other writing programs creating CEC programs.

Scholarly Context: The Challenge of Determining Learning in CEC Programs

We understood early on in the process of designing this study that it would be difficult to reliably generalize about students’ learning from and experiences with Disciplinary Writing Consultants (our name for Course-Embedded Consultants) across courses. Each student brings to the course their own prior learning and experiences with writing; faculty, from across the disciplines, have varying degrees of experience teaching writing prior to working with a Disciplinary Writing Consultant (DWC); and DWCs bring different levels of experience as well. Our program goal is not to offer a standardized model of consulting, but rather for our DWCs and faculty to work together to enhance writing instruction in the course, bring a model of writing center consulting to students, and identify ways to support students’ writing needs within the context of the course. Given these purposes, variation is to be expected and indeed welcomed.

Other CEC programs experience similar variation in consulting which, though understandable and even welcomed, can also lead to variation in a program’s success. In their article as part of a Praxis special issue on course-embedded consultants, published in 2014, Kelly Webster and Jake Hanson discuss several publications that reflect on the “striking” unevenness in CEC programs’ success. For instance, Terry Zawacki discusses tensions between tutors and faculty that can prevent faculty growth in teaching with writing; Hughes and Hall found faculty who resisted fully integrating the CEC or who did not effectively negotiate a shared authority (27; see also Soven 206). Webster and Hanson identify additional features that complicate success: managing collaborative logistics, need for faculty buy-in (especially regarding the writing process), feedback on writing, and collaboration with CEC; faculty-CEC integration; and student and faculty willingness to consider and respond to feedback. While the student survey responses did not reveal this unevenness, and thus we don’t report on it here, we know from experience working with the program that some of the same factors showed up in participating courses over the years.

From extensive research conducted in the writing studies field, we know that students’ writing development takes time, and because writing development is so complex and context-specific, it is challenging to isolate features of writing to assess with an eye to identifying improvement. In some contexts, looking at both direct (e.g., student writing) and indirect (e.g., students’ perspectives, course assignments, instructional techniques) instruments together can lead to an understanding of student writing improvement, with “writing improvement” clearly defined; however, with the variation in our DWC program, any definition of improvement would vary from course to course, making it challenging to assess the program overall. Additionally, previous studies have described how difficult it can be to assess the efficacy of writing consulting on student writing improvement: as early as 2001, Casey Jones suggests that “the quantitative study of writing center efficacy is invalid” because consulting sessions differ so widely and because it is so difficult to define “good writing” or “growth in writing proficiency” (5). In a review article from 2012, Mariam Gofine found only two studies published after Jones’ article that attempted to measure the writing quality before and after consulting (44). Questioning what is meant by writing quality or improvement, Teresa Thonus argues that “it is imperative . . . to ask what factors students and tutors appeal to in accounting for the perceived ‘success’ of writing tutorials” (112-113). And, more recently, Jo Mackiewicz and Isabelle Thompson (2015) acknowledge that identifying the impact of tutoring on student writing “is not only vastly complex but also theoretically questionable” (179). Beyond these challenges, perhaps more valuable, then, is to focus on aspects of writing that invite us to think more broadly about students’ writing experiences, such as their attitudes toward writing, sense of control over the writing process, openness to feedback on their writing, and feelings of confidence, agency, or efficacy as a writer. Our study, which surveyed students on their perceptions of learning, attempts to contribute to this broader understanding of writerly growth.

Institutional Context

This study presents the results of our analysis of a selected subset of student survey data, collected over seven years of Elon University’s Disciplinary Writing Consultant (DWC) Program, housed within the university’s Center for Writing Excellence (comprising The Writing Center and Writing Across the University, our version of WAC). The DWC program assigns writing consultants who have extensive academic preparation and hands-on experience working in The Writing Center to discipline-specific courses as DWCs. From Fall 2016 to Spring 2023, the CWE provided DWCs to 82 courses across the disciplines, including Arts Administration, Communications, Economics, Education, English, History, Public Health, and Political Science. Each semester, we have between 4-9 DWCs attached to the same number of courses. In the first couple of years of the program, during the pilot phase, we invited selected faculty to participate–typically faculty who had previously participated in faculty development through Writing Across the University. Since 2019, we’ve invited faculty participants to apply via the campus listserv. In the earlier years of the program, we permitted faculty to continue indefinitely; however, as interest has grown, we now limit participation to one year, at which point faculty must take a break before being eligible to reapply after a year off. Each semester, some faculty request to see their course’s survey responses in order to make improvements for future semesters. Beyond this local assessment, our goal for gathering student feedback is to assess, over the long term, the benefits of providing DWCs to discipline-specific courses. The survey instrument has IRB exemption status, and students sign a consent form at the beginning of the semester; the consent form indicates their willingness to complete the survey anonymously.

Elon’s Disciplinary Writing Consultant (DWC) Program emerged as one of many writing initiatives from our university’s Quality Enhancement Plan (2013-2018), which focused on enhancing writing and writing instruction across the university. The goal of the DWC program is to provide consultant support for writing in the disciplines and to enhance the instruction of writing across campus by inviting faculty to integrate writing and peer support into their courses. Now that the application process for participating is open to all faculty, we find that faculty who have been involved with some prior WAU programming tend to be better prepared to take on a DWC for their course. Faculty receive a stipend for participating–this is a way to demonstrate that their time is valued and so that we can expect faculty to attend training, mentor the DWC, and administer the survey. One important aspect to note about the program is that because the DWC does not regularly attend class, most faculty require or incentivize their students to meet with their DWCs in one-to-one meetings outside of class, typically several times over the course of the semester.

Study MEthods

Survey Instrument

Since Elon University’s Disciplinary Writing Consultant program commenced, each semester we have asked faculty teaching a course with an assigned DWC to administer two surveys to students in the course. The first survey (start-of-semester, or “start-survey”) is administered at the beginning of the semester, after the DWC role has been explained to the students but before the students have started meeting with them. The second survey (end-of semester, or “end-survey”) is administered in the last week or two of the course. We strongly encourage faculty to dedicate class time to administering the survey as this leads to a higher response rate. The survey was created in Qualtrics and can be viewed in this Google document.

Following a question that asks students to identify which course they are in, the start-survey comprises seven questions in two sections. The first section asks them to select writing strategies they learned prior to the class or strategies they already use: four questions ask them to identify brainstorming/invention, arrangement/organization, revising, and editing strategies. There is a pull-down menu of options to choose from and a blank space to write in other options. The second section asks three open-ended questions:

“What kinds of things about writing do you expect to learn from the Disciplinary Writing Consultant?”

“What kinds of things about writing do you expect to learn from the Professor?”

“Do you think your writing process will change after taking this class? If so, please explain.”

The end-survey also begins with a question that asks students to identify which course they are in. The first section asks four questions about the writing strategies they learned in the class, in the same four areas as the start survey (brainstorming/invention, arrangement/organization, revising, and editing). In the end survey, these questions are open-ended. The second section asks students four additional open-ended questions:

“In what ways, if any, do you think your writing or your writing process has changed after taking this class?”

“What kinds of things about writing, if any, did you learn from your professor in this class?”

“What kinds of things about writing did you expect to learn that you did not learn from your professor?”

“What kinds of things about writing, if any, did you learn from your Disciplinary Writing Consultant in this class?”

The third section is a couple of multiple choice or Likert-scale questions: “Have you worked with a Writing Consultant in the Writing Center prior to this course?” (Yes/No); and “How likely are you to visit the Writing Center and work with a consultant on future writing projects?” (on a scale from Extremely likely to Extremely unlikely).

We asked questions regarding the stages of the writing process (brainstorming/invention, arrangement/organization, revising, and editing) because we used these terms during our University’s Quality Enhancement Plan for accreditation, in Writing Across the University (our WAC program) faculty development workshops, and on The Writing Center’s in-take appointment form. Although we also collected de-identifiable information from each student, as we had planned to compare each student's start- and end-survey responses, we determined that tracking individual student’s perceived growth was unreliable: for each course, some students would miss one of the surveys or they would forget what they had selected or written at the beginning of the semester. In addition, occasionally faculty would forget to administer one or both of the surveys.

Selecting Questions and Responses to Analyze

When we started to analyze survey responses to understand the benefits of the program to students, we quickly realized we needed to be selective. In an attempt to limit some of the variables, we focused on survey responses from courses that had worked with a DWC for two consecutive semesters and courses that had complete survey data (“complete” means that the faculty member had successfully administered both the start- and end-surveys for two semesters in a row). These two factors help limit the study to some of the faculty who are most committed to the DWC program. Through this selection process, we ended up with 14 data sets–start and end of semester surveys, from at least two semesters each course (three semesters for one course), and from three courses (see Table 1). Because faculty administer the survey in class, the response rate is consistently high with some exceptions (Economics, Fall 2020, end of semester; Education, Spring 2022, end of semester).

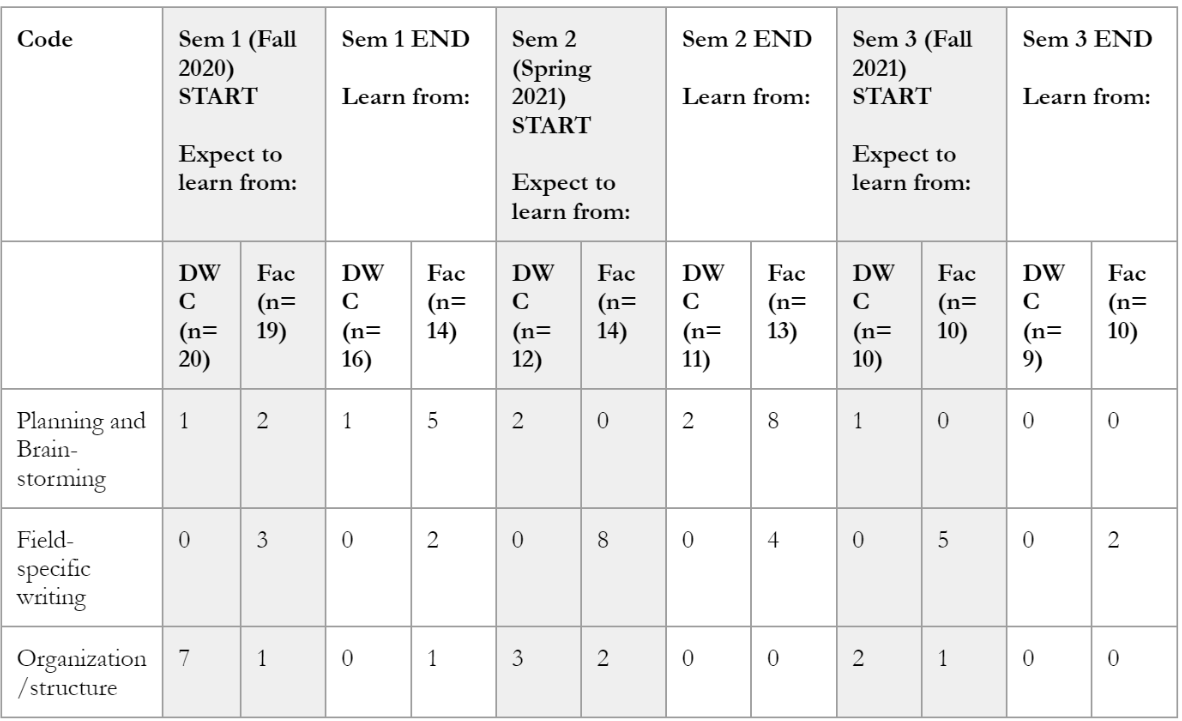

Table 1: Survey response rate for three courses with an assigned DWC.

Coding Process: Stage 1

Using a combination of an emergent and predefined thematic coding process (Saldaña), we read sample survey sets and discussed emergent themes (discussed in more detail below). We then both separately coded topic episodes (Geisler) in two more survey sets, then we swapped, discussed, and drafted a code book. At this point in the coding process, we introduced some predefined themes to help us organize and make sense of the codes and to connect to the goals of the DWC program, as well. The predetermined terms that we introduced relate to the writing process (planning, revising, editing) and had been used during the university’s Quality Enhancement Plan and thus faculty were likely to be familiar with them; we also introduced the theme of “field-specific writing concepts,” as we anticipated that faculty would expect students to learn to write according to the conventions of their discipline. After we introduced these terms, we then coded two more survey sets and again discussed and revised the code book. For this entire process, we focused on two open-ended questions from the survey: “What do you expect to learn about writing from your Disciplinary Writing Consultant?” (from the start survey) and “What did you learn about writing from your Disciplinary Writing Consultant?” (from the end survey). We selected these questions because they were open-ended and needed to be coded iteratively. Once we were done coding these four questions, we decided that we wanted to focus on these data and that we had enough information to analyze.

Table 2: Code Book for “What do you expect to learn about writing from your DWC or professor?” and “What did you learn about writing from your DWC or professor?”

Results

In this section, we present our most commonly-identified codes in the four survey questions we analyzed for this article for three undergraduate courses with DWCs. As a reminder, the questions are:

START of Semester Survey:

“What kinds of things about writing do you expect to learn from the Disciplinary Writing Consultant?”

“What kinds of things about writing do you expect to learn from the Professor?”

END of Semester Survey:

“What kinds of things about writing, if any, did you learn from your professor in this class?” “What kinds of things about writing, if any, did you learn from your Disciplinary Writing Consultant in this class?”

Economics 1100: Principles of Economics

This introductory Economics course is one of our most successful DWC-supported courses. The professor has taught the course many times and, over the years, reports that he has found value in partnering with his DWC to revise the course and improve the students’ learning experience. As a 1000-level course, it attracts first-year students interested in Economics; it’s also a general elective requirement for various majors, including Business, Accounting, etc. While the professor was committed to getting his students to complete the survey, note the low response rate to the survey in the second semester (Fall 2020); while students were back to in-person courses at our institution, it remained a challenging semester for instructors and students.

In several areas, students had expectations for learning at the beginning of the semester and did not perceive to have learned these things by the end of the semester. Students expected to learn more “general college writing” and planning from their DWC than from their professor, but this turned out not to be something they reported learning. In addition, students expected to learn how to write like an economist from both their DWC and the faculty member (in the first and second semester) but did not perceive to have learned this by the end of the semester. In these cases, students expected to learn more than they perceived to have learned, with one exception: organization/structure was an expectation and a perceived learning outcome of the course, especially in Spring 2020.

Education 2980, Children’s Literature and Arts Education

This 2000-level course attracts primarily Education majors and minors and, because the topic is related to literature, English majors and minors looking for an elective. As we analyzed the survey responses, we noted that students wrote quite a bit in their open-ended responses (more than for the other courses), perhaps due to their interest in teaching and writing. Although the end-survey response rate is low in the second semester (Spring 2022), the instructor was able to get some students to complete the survey, so it’s included here.

As with the Economics 1100 level course, students in this Education course also expected to learn something about “general college writing” from their DWC, rather than their professor. However, they did perceive learning this from their faculty, at least in the first semester. In the second semester, students expected to learn concise writing from both DWC and faculty; however, no student perceived learning this by the end of the term. Strikingly, most students did not expect to learn anything about field-specific writing and yet 13 perceived learning this from their faculty by the end of the first semester. For this course, field-specific writing included writing a literature review, theoretical framework, analysis and synthesis, and lesson plans for teaching. It’s important to note that in showing the most commonly coded writing elements, the table fails to show the great deal of variation in students’ expectations. For instance, in spring 2022, 17 students identified 13 discrete expectations from their faculty and 10 from the DWC.

Arts Administration 3300: Legal Aspects of Arts and Entertainment

This Arts Administration course attracts primarily Fine Arts and Arts Administration majors and minors. The instructor of this course was able to successfully administer the survey for three consecutive semesters, so we’ve included highlights from all these semesters here.

As with the other courses, the number of responses in each category are small, and patterns are difficult to discern. What is noteworthy is that students indicated they learned planning and brainstorming from their instructor and less so from their DWC in the first and second semesters (though not the third). In this course, planning and brainstorming meant that the instructor broke a project into chunks, or scaffolded, a larger assignment. No student expected to learn about field-specific writing from their DWC, but some expected to learn this from their instructor. Some students (though less than expected to based on their responses to the start-survey) did learn discipline-specific writing from their instructor, and no one indicated they learned this from their DWC. In this course, discipline-specific writing means grant applications and legal documents. Finally, some students expected to learn about organization and structure from their DWC, but no student indicated that they learned this from them.

As with the other courses, the number of responses in each category are small, and patterns are difficult to discern. What is noteworthy is that students indicated they learned planning and brainstorming from their instructor and less so from their DWC in the first and second semesters (though not the third). In this course, planning and brainstorming meant that the instructor broke a project into chunks, or scaffolded, a larger assignment. No student expected to learn about field-specific writing from their DWC, but some expected to learn this from their instructor. Some students (though less than expected to based on their responses to the start-survey) did learn discipline-specific writing from their instructor, and no one indicated they learned this from their DWC. In this course, discipline-specific writing means grant applications and legal documents. Finally, some students expected to learn about organization and structure from their DWC, but no student indicated that they learned this from them.

Table 3: Raw data count of most commonly-identified codes for Economics 1100 course with a DWC.

*Because of the higher numbers here, we’ve separated these two codes.

Table 4: Raw data count of most commonly-identified codes for Education 2980 course with a DWC.

Table 5: Raw data count of most commonly-identified codes for Arts Administration 3200 course with a DWC.

Discussion

Overall, from our analysis of the start and end surveys together, the results seem to show a lack of students’ perceived learning from their DWCs as well as little learning from their instructor, especially in comparison to what they expected. For the Economics course, more students expected to learn about general college writing, planning, field-specific writing, and writing like an economist than they actually did (or perceived to). For the Education course, although the numbers are small, more students expected to learn about general college writing and about concise writing than they actually did (or perceived to). And for the Arts Administration course, few to no students perceived to have learned planning, field-specific writing, and organization/structure from their DWC, though some students learned these things from their instructor. Where we see common expectations for learning (for example, seven students in the first semester of the Arts Administration course expected to learn about organization/structure; in the second semester of the Education course, students expected to learn about concise writing from both their DWC and their instructor), it may be the case that these are writing elements the professor or the DWC specifically mentioned right before the students took the survey, which is why the expectations were on students’ minds.

Overall, as researchers and program administrators, we learned more about student expectations for learning than about perceived student learning. While the variation in responses and contexts makes us cautious about identifying patterns across the three courses, it appears that the students expected to learn more general and non-field specific writing aspects (such as elements of the writing process) from their DWC and field-specific writing aspects from their instructor. As the course level advances, students’ expectations appear to become more focused or narrow in scope: for example, in the 1000-level Economics course, 12 students expected to learn about “general college writing” from their DWC and one student expected to learn this from their instructor, whereas no students in the 3000-level course expected to learn about general college writing. As students progress in their degree, it’s to be expected that they no longer feel the need to learn about general college writing and instead their expectations become more specific and advanced. The fact that students expected to learn about general college writing at all, in a disciplinary-writing course, suggests that students’ expectations about writing may be based on a potential lack of understanding of academic writing: what general college writing is (if general college writing even exists); how disciplinary writing might differ from the writing they did in, say, a first year writing course; how much learning about writing can be achieved in one semester; and what learning related to writing even means (if, for instance, students have a narrow view of learning as content knowledge). When we ask students about their expectations for learning, then, we need to narrowly define writing and learning—and teach students language for talking about their learning on a metacognitive level—or risk students being unable to identify when learning has actually occurred.

Looking across the survey responses regarding both the DWC and the faculty, we expect that students would have considered the questions about their DWC and their faculty simultaneously, and then chose to write different responses accordingly. However, we don’t know if this is because students believed they would or did learn something different from each or because the very fact of being asked two questions prompted them to assume we must expect them to learn/have learned something different.

final thoughts & next steps

In our analysis of students’ survey responses to questions about learning in courses with an assigned Disciplinary Writing Consultant, we expected to see that students are learning complementary things about writing from their DWC and their instructor. We also sought to understand how students’ expectations for learning at the beginning of the course align with their perceived learning at the end of the course. While the presentation and analysis of our data embraces variation across individual courses in order to examine learning in the course most holistically, we did not find much alignment between the beginning and end of each course; in fact, we did not find much evidence of students’ perception of learning at all.

While we might feel disappointed by this, we understand that helping students see the benefit of working with a DWC proves hard to do. For example, in Steffen Guenzel, Daniel S. Murphree, and Emily Brenna’s survey-based study, “Re-Envisioning the Brown University Model: Embedding a Disciplinary Writing Consultant in an Introductory U.S. History Course,” they found mixed, even contradictory, attitudes from students who worked with a course-embedded consultant (CEC) in a discipline-specific course. The study reported a range of contradictory responses: two-thirds of students did not find the CEC useful, some students indicated that they benefited from the CEC, students who didn’t work with a CEC appreciated that a CEC was available, and students wanted the CEC to have a greater role in the course—perhaps even the same students who didn’t utilize them (74-75). Seeing the results of Guenzel et al.’s study reminds us of the limitations of student surveys as a sole measure of course learning, as well as the limitations of expecting learning to occur after one or two meetings with a writing consultant.

Our other goal for this study was to analyze the survey responses in order to understand what we might do differently to manage students’ expectations and enhance their perceptions of learning in the course. Regarding students’ expectations, one change we are making is designed to improve students’ understanding of the DWC’s role in their course. We have created a standardized introduction to the DWC program, which each DWC delivers at the beginning of the course; we have also added more focus in the faculty training on the importance of the faculty making expectations clear for the DWC and for the students. Regarding students’ perceptions of learning, because of the contradicting experiences and attitudes of the students, Guenzel et al.’s solution was to require or otherwise incentivize students to meet with their CEC. In our case, most DWC faculty already incentivize students by requiring them to meet with the DWC once or twice during the semester or offering extra credit when the students do meet with a DWC. What this shows us, not surprisingly, is that requiring one or two meetings with the DWC per semester does not lead to an enhanced perception of learning in the course. While we would always hope to see indications of students’ perceptions of learning–and in some cases, we do see this–we also need to consider how the purpose of the DWC program goes beyond providing individual support to student writers. As part of our University’s Quality Enhancement Plan, the DWC program was created to also guide faculty to integrate writing into their courses and to provide an opportunity for mentoring and professionalization for the DWCs. Thus, to fully assess the value and benefits of our DWC program, we would need to holistically study all of these aspects together.

For other programs with course-embedded consultants (CEC) such as ours, we offer some final thoughts and recommendations.

Select faculty participants carefully. We have found that the most effective faculty—the ones who best integrate the CEC into their courses—are those who have previously participated in faculty development regarding the teaching of writing.

Invest time in training and preparing faculty to fully understand the value of peer writing support and the need for ongoing mentoring of the CEC.

Train the course-embedded consultant (or faculty) to effectively explain the program to students in the course; this explanation will likely need to be delivered more than once. Emphasize the importance of the CEC visiting the class to introduce the program.

Ask the faculty to set clear, and perhaps modest, expectations for how the CECs might benefit the students in the course, especially emphasizing that the student is responsible for their own learning and growth.

Encourage faculty to teach students terminology around writing and learning to write—such as audience analysis, revision, and reflection—to help students identify moments of learning that they may otherwise fail to recognize.

Provide opportunities for the CECs to learn from each other, sharing strategies for working with the faculty member and students.

Finally, design assessments that offer opportunities to learn broadly about students’ experiences and be prepared for wide-ranging responses. This may include giving students an opportunity to reflect on what they learned about writing throughout the term, and especially after completing a writing assignment.

notes

We use Course-Embedded Consultants (CEC) when talking about the model in general, and Disciplinary Writing Consultants (DWC) when talking about the Elon-specific program.

works cited

Bleakney, Julia, Russell Carpenter, Kevin Dvorak, Paula Rosinski, and Scott Whiddon. “How Consultants and Faculty Perceive the Benefits of Course-Embedded Writing Consultant Programs.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 44, no. 7-8, Spring 2020, pp. 10-17.

Carpenter, Russell, and Scott Whiddon. “‘The Art of Storytelling’: Examining Faculty Narratives from two Course-embedded Peer-to-Peer Writing Support Pilots.” SDC: A Journal of Multiliteracy and Innovation, vol. 20, no. 1, 2015, pp. 85-107.

Dvorak, Kevin, Julia Bleakney, Paula Rosinski, and Rusty Carpenter. “Effectively Integrating Course-Embedded Consultants Using the Students as Partners Model.” National Teaching and Learning Forum, vol. 9, no. 1, December 2019, pp. 7-9.

Dvorak, Kevin, Shanti Bruce, and Claire Lutkewitte. “Getting the Writing Center into FYC Classrooms.” Academic Exchange Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4, Winter 2012.

Geisler, Cheryl. Analyzing Streams of Language: Twelve Steps to the Systematic Coding of Text, Talk, and Other Verbal Data. Pearson/Longman, 2004.

Glotfelter, Angela, et al. “Changing Conceptions, Changing Practices: Effects of the Howe Faculty Writing Fellows Program.” Changing Conceptions, Changing Practices: Innovating Teaching across Disciplines, edited by Angela Glotfelter et al., University Press of Colorado, 2022, pp. 27-45. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv335kw99.6.

Gofine, Miriam. “How Are We Doing? A Review of Assessments Within Writing Centers.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 32, no. 1, 2012, pp. 39-49.

Guenzel, Steffen, Daniel S. Murphree, and Emily Brenna. “Re-Envisioning the Brown University Model: Embedding a Disciplinary Writing Consultant in an Introductory U.S. History Course.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014, pp. 70-76.

Henry, Jim, Holly Bruland, and Jennifer Sano-Franchini. “Course-Embedded Mentoring for First-Year Students: Melding Academic Subject Support with Role Modeling, Psycho-Social Support, and Goal Setting.” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, vol. 5, no. 2, 2011, Article 16.

Hughes, Bradley, and Emily B. Hall. “Rewriting Across the Curriculum: Writing Fellows as Agents of Change in WAC.” Spec. issue of Across the Disciplines: A Journal of Language, Learning, and Academic Writing, 29 Mar. 2008.

Jones, Casey. “The Relationship Between Writing Centers and Improvement in Writing Ability: An Assessment of The Literature.” Education, vol. 122, no. 1, 2001, pp. 2-19.

Macauley, Jr., William J. “Insiders, Outsiders, And Straddlers: A New Writing Fellows Program in Theory, Context, And Practice.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014, pp. 45-50.

Mackiewicz, Jo, and Isabelle Thompson. Talk About Writing: The Tutoring Strategies of Experienced Writing Center Tutors. 2nd Ed. Routledge, 2018.

Miller, Laura K. “Can We Change Their Minds? Investigating an Embedded Tutor's Influence on Students' Mindsets and Writing.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 38, no. 1-2, 2020, pp. 103-130.

Oleson, Kathryn C., and Knar Hovakimyan. “Reflections on Developing the Student Consultants for Teaching and Learning Program at Reed College.” International Journal for Students As Partners, vol. 1, no. 1, 2017, https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3094.

Regaignon, Dara Rossman, and Pam Bromley. “What Difference Do Writing Fellows Programs Make?” The WAC Journal vol. 22, 2011, pp. 41-63. DOI: 10.37514/WAC-J.2011.22.1.04.

Webster, Kelly and Jake Hansen, “Vast Potential, Uneven Results: Unraveling The Factors That Influence Course-Embedded Tutoring Success.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014, pp. 51-56.

Saldaña, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Fourth edition, ed. SAGE, 2021.

Titus, Megan, Jenny Scudder, Josephine Boyle, and Alison Sudol, “Dialoging A Successful Pedagogy For Embedded Tutors.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014, pp. 15-20.

Zawacki, Terry, et al. “Writing Fellows as WAC Change Agents: Changing What? Changing Whom? Changing How?” WAC Clearinghouse, 29 Mar. 2008.