Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 21, No. 3 (2024)

A CHAT Analysis: Narrating the Writing Center’s Formative Period

Don Moore

SUNY Polytechnic Institute

mooredr@sunypoly.edu

Abstract

From the recognized beginning of the “laboratory” movement in composition instruction, teachers have sought to employ new and more practical methods useful in developing student writing. Such trends continue today as new generations of students enter the academy and new challenges emerge. From such conditions, we might see how components within a system of activity work together to meet objectives and develop outcomes within the shared dialectic of an activity system. With this idea in mind, this article reviews writing center-related scholarship from the late 1880s through the early 1940s to trace emerging contradictions in laboratory teaching’s praxis. Through the evaluation of laboratory teaching’s textual artifacts using Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT), I present a narrative about the development of the earliest writing center praxes: The Formative Period.

With this article, I look to narrate an epochal beginning for writing center activity and present the development of guiding principles we find in our writing center work today. Through the process of revealing historical impulses, this article offers a view of writing center praxes in their elemental stage: The Formative Period, early 1890s-early 1940s. Ultimately, this article will show how the writing center is an activity that, over time, has mediated old system contradictions and developed new methods born of self-reflection, debate, evaluation, and progressive mediation, which continues to evolve. As communities like writing centers re-create themselves—through pushing and pulling, conflict and resolution, tension and release—they birth new realities, which all begins with the Formative Period.

Over the last one hundred and fifty years or so, writing center history has unfolded and developed in some predictable and unpredictable ways. As each new generation enters the writing center diaspora, new conversations have helped shape our ever-evolving scholarship; however, many of these conversations unintentionally remain absent from notable writing center histories. Thus, an historical lineage that exposes important but otherwise forgotten discussions, which may provide important nuance to writing center pedagogies, seem to only exist within a larger, unspoken framework of ideas. These are the frames under which many writing centers operate, yet their full histories and inclusion into writing center lore are not quite understood. In fact, Neal Lerner recognizes this reality in his 2003 Composition Studies article “Punishment and Possibility: Representing Writing Centers, 1939-1970”: “For some,” he says, “writing center history simply doesn’t exist” (53). Outside of Lerner’s work, there is a relative lack of research that demonstrates the historical growth of the writing center as we know it today. With this in mind, it may be time to narrativize the evolution of writing center history in order to gain a fuller understanding of where our most salient guiding principles originated.

Such an investigation, I suggest, follows Peter Carino’s argument in his 1996 article, “Open Admissions and the Construction of Writing Center History: A Tale of Three Models.” Carino makes the claim that writing center studies “need[s] to construct an elaborately detailed and historiographically sophisticated model that would more effectively account for the complexity of writing center development than has previous historical work” (30). For further study, Carino suggests a cultural frame may best serve as a model for developing the historicity of writing center work. In fact, a cultural frame may help expose the subtleties of composition’s history that have contributed to the development of writing center pedagogy. Additionally, just as Carino’s work opens the door for charting writing center praxes and scholarship, so too does Elizabeth Boquet’s 1999 College Composition and Communication article “‘Our Little Secret’: A History of Writing Centers, Pre- to Post-Open Admissions.” Arguing that early writing laboratory scholars “framed the work of the writing lab as encouraging dialogue, even dialectic, much as we in the writing centers do today” (45), Boquet’s recognition of the “dialectic” in writing center praxis expands the possibilities for identifying how a pedagogical dialectic has helped shape enduring writing center praxes. Both Carino and Boquet, then, pave the way for today’s researchers to identify how a cultural dialectic exists on the periphery of our immediate writing center spaces. In other words, what are the historical origins of a writing center dialectic? How might we find the origins of the writing center in composition’s history? What do tensions and resolutions found in composition’s history have to tell us about our current conceptualizations of writing center space?

In his 2009 book The Idea of a Writing Laboratory, Neal Lerner begins to answer these questions by focusing on late nineteenth-century composition instructors who employ writing labs. “In science,” he says, “hands-on learning was meant to overcome the problem that Louis Agassiz of Harvard described in the mid-nineteenth century: ‘The pupil studies nature in the classroom, and when he goes out of doors he can not [sic] find her’” (3). Thus, Lerner focuses on the “laboratory method” (or the hands-on approach) in writing classrooms as it began to take shape at the end of the nineteenth-century. Therein, he identifies Preston W. Search as an instrumental figure in the writing laboratory movement:

I first came across Search’s concept of “laboratory methods” in my quest to find the first college-level writing center. It struck me then and now that Search’s description of the ideal teaching conditions—one-on-one instruction tailored to students’ particular needs—echoes the rationale for writing centers as ideal places for learning and teaching writing. (The Idea 5)

Lerner’s discovery helps identify “tensions between pedagogy and curriculum through the experiences of one late 19th century educational reformer, Preston W. Search” (4). With this note, Lerner demonstrates how Search became one of the leading practitioners of laboratory teaching and provides a specific view of laboratory instruction’s—as well as the writing center’s—beginnings. My article, then, looks to find other rich historical figures like Search existing on the periphery and in the archives of writing center lore whose episodic observations continue to inform our work today.

In the end, Carino, Boquet, and Lerner each offer new avenues for research and historical analyses. Carino offers the view that a cultural frame for analysis may be most appropriate as we look to analyze a totality (beginning with composition pedagogy) of writing center history. Similarly, Boquet opens the door for analysis by recognizing the social construction and dialectic inherent in activity, and in doing so, she offers opportunities to discover a dialectical history between composition studies and writing center pedagogy which continues to inform writing center work today. Finally, Lerner’s rich historical work invites a holistic approach to trace the lineage of writing center history. Providing a starting point with Search, Lerner’s work invites further opportunities to include other forgotten conversations as part of the ancestry of writing center development.

Part of what I look to accomplish with this article, then, aims to take over where Carino leaves off. Viewing the history and development of the writing center through the lens of Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) resolves Carino’s dilemma of an either/or dichotomy, for CHAT represents both an evolutionary and dialectical model of analysis. Therefore, I posit that CHAT, a cultural model like that which Carino advocates, will “begin to elaborate, more than previous models have, a history accounting for the multiple forces at play at various moments” in writing center history (Carino, “Open” 39). Situating the cultural-historical development of the writing center squarely within the frame of CHAT may also help expose those rich meta-dialectical contributions to historical writing center lore Boquet intuits as they emerge throughout composition’s history. Further, responding to Nancy Grimm’s address to the International Writing Centers Association Conference in Las Vegas in 2010, I argue that a framework like CHAT that interrogates the movement of history has the “potential to bring divergent perspectives into contact with one another for the possibilities of transforming perspectives and generating new understandings” (“New” 26). With this, I look to provide an interpretation of history through which I believe writing centers have emerged, specifically, through the impetus of composition’s model of laboratory teaching.

Certainly, writing centers did not pop out of thin air, so to demonstrate how they began to develop, I offer a careful look at the first fifty years (or so) of laboratory teaching as a precursor to writing center work through the lens of CHAT. It is important to begin with composition practices, i.e., laboratory classrooms, to illustrate the beginnings of writing center work, for these classroom practices foreground the guiding principles found in today’s writing center spaces: laboratory/writing center work is experimental, student-centered, and collaborative. The work (including that of teachers and consultants) is flexible, and environmental factors and technology play an instrumental role in laboratory/writing center work. As this article will demonstrate, when the composition community engages in the pushing and pulling, conflict and resolution, tension and release of pedagogical change, they birth new realities. Through the process of revealing historical impulses that established laboratory writing practices in composition classrooms, this article argues that the development of current writing center praxes began during the laboratory classroom movement of the late nineteenth-century, thus establishing the first stage of writing center development: The Formative Period.

Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT)

Rooted in Vygotsky’s original conceptualization of activity as a model of development, Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) acts as the interpretive agent for my work. Specifically, I employ third-generation activity theorist Yrjö Engeström’s framework of nested triangles to conduct a robust inquiry of writing center practices. In order to uncover trends and situate the development of writing center work through composition studies’ organically active, creative, and mediational laboratory model, I explore what Vassily Davydov argues in Perspectives on Activity Theory are “the historical conditions for activity that transforms reality according to the laws of its own perfection” (43). Thus, I view writing center activity as that, which over time, has been born of self-reflection, debate, improvement, and evaluation, specifically through the composition community’s dilemmas. Much like early laboratory classroom practitioners cross-appropriated the concept of the laboratory from the realm of the sciences to that of the composition classroom, writing center practitioners have also adopted the laboratory method from composition as that which guides writing center practice. In turn, each generation’s dialectical contributions inform the burgeoning practices that follow, and, as they expand, practitioners share strategies, create connections, and further craft a lasting blueprint for the writing center’s future.

Beginning with Lev Vygotsky’s subject-object-mediating artifact triad, Vygotsky aims to illustrate the “means by which human external activity is aimed at mastering, and triumphing over, nature” (55). With “human external activity” in mind, leading CHAT critic Andy Blunden, in his 2010 book An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity, argues the implication of sociality exists in Vygotsky’s original triad, for “social entities and individual personalities mutually constitute and form one another . . .” (171).[1] However, second-generation activity theorists including Vygotsky’s contemporary psychologists Alexei Leont’ev and Alexander Luria argue “collective object-oriented activity is of central importance” (Engeström, “Expansive Visibilization” 65). Therefore, rather than merely accepting sociality as an inherent component of the human experience, Leont’ev and Luria build on to Vygotsky’s original frame to illustrate how collective activity may be imagined. For second-generation activity researchers like Leont’ev and Luria, the shared dialectic between individuals and groups (i.e., early compositionists and emerging writing center practitioners), must exist for any activity to exist; therefore, the community must be an external component of the analysis.

Today, third generation activity theorists such Engeström apply the expanded CHAT model of Luria and Leont’ev to the workplace with Engeström’s model derivative of the concept of dialectical activity: “The whole . . . [is] perceptible in every part” (Blunden 27). With this frame placed in the context of workplace development, I subsequently use Engeström’s CHAT framework to analyze composition’s model of laboratory teaching from which, I argue, modern-day conceptualizations of writing centers have emerged. Illustrated in Figure 2, with seven distinct concepts, the subject is the central figure in the system of activity. For this study then, laboratory teaching, the student, the consultant, or the writing center itself may be the subject. The object, or objective, is that which the system of activity aims to accomplish with mediating artifacts comprising those tools which the system employs to help the subject meet its goals with rules guiding the activity. Finally, those in the community i.e., students, consultants, faculty, and administrators, all have a role to play as a division of labor among members coalesces to meet objectives and realize outcomes of the activity.

With the dialectic of a system driven by objective-related motives, the activity within composition classrooms at the end of the nineteenth-century situates the laboratory movement as a response to a lecture-recitation model that did not result in writing improvement among new populations of students. My argument herein posits that writing center development, emerging from the laboratory movement, remains in constant flux with tensions mediated throughout its evolution. As Blunden explains “the whole point [of CHAT is] to bring out the contradictions and show how they are resolved in actuality” (173). Marking the beginning of the laboratory movement then, and ultimately the writing center, Engeström’s CHAT frame is useful in illustrating contradictions in the system of the lecture-recitation model. By examining John Franklin Genung’s and Fred Newton Scott’s early critique of nineteenth century composition classrooms, we see a rationale for the placement of laboratory classrooms within composition classrooms, and we can see the birth of the writing center.

For example, in Genung’s 1887 description of "The Study of Rhetoric in the College Course,” he identifies contradictions in the composition classroom:

English is at a disadvantage; the very fact that it is compulsory weights it with an odium which in many colleges makes it the bugbear of the course. This ill repute was increased in the old-fashioned college course by the makeshift way in which time was grudged out to it in the curriculum. . . Now every teacher knows a once-a-week study cannot be carried on with much profit or interest; it cannot but be a weariness to student and instructor alike. (173)

Noting the marginal treatment and poor results of composition curricula, Genung sees the whole of composition curricula in need of reform. Similarly, at the University of Michigan, Scott argues: “We hardly learn the names and faces of our hundreds of students before they break ranks and go their ways, and then we must resume our Sisyphean labors” (179-80). Thus, Genung’s and Scott’s criticisms offer a view of how Engeström’s CHAT framework may be applied.

Figure 3 reveals that while the lecture-recitation classroom certainly uses its tools, some, if not all, of them disrupt the achievement of objectives, for such a curriculum fails to engage students, and a breakdown of the system ensues. With lecturing as a tool, students do not engage writing in any real-world sense. The lecture fails to develop students’ composing skills with its impractical application in large, heterogeneous classrooms, and recitation and theme work fail to stimulate or challenge students’ individual growth. This, in turn, generates ambiguous rules for the composition classroom promoting a skewed division of labor. Certainly, instructors employ the banking model with ease, but as Freire’s work suggests, this does not necessarily help students’ understanding of writing concepts.[2] In turn, the outcome of a broken system is to develop a new one: Laboratory Teaching.

Genung argues that “laboratory work” best defines his approach at Amherst: “each of these courses is a veritable workshop . . . each professor being supreme in his sphere, to plan, carry out, and complete according to his own ideas—a trio in which the members work side-by-side, in co-operation rather than in subordination” (174). In their approach to using a laboratory writing praxis, Genung and Scott exemplify the collaborative and reciprocal nature of education. Today, this coincides with Stephen North’s leading essay, “The Idea of a Writing Center”: “What we want to do in a writing center is fit into—observe and participate in—this ordinarily solo ritual of writing” (70). Thus, with Genung and Scott’s implementation of the “laboratory method” or “laboratory system,” a new and more practical method in developing student writing emerges. In turn, as practitioners begin identifying contradictions and seeking responses to system tensions, the available literature provides a striking sense that during this period and into the early twentieth-century, teachers of composition began experimenting widely with laboratory methods, ultimately laying the groundwork for the emergence of today’s writing laboratories and writing centers.

With the initial movement by Genung and Scott, Engeström’s CHAT framework helps reveal how a community may develop or recreate itself. Therefore, using Engeström’s CHAT model as a ‘whole,’ I look to develop a complex web of interrelated parts developed and detailed over time. Engeström explains: “Goal-directed individual and group actions, as well as automatic operations, are relatively independent but subordinate units of analysis, eventually understandable only when interpreted against the background of entire activity systems” (“Expansive Learning” 136). With an application of CHAT to review activities stretching across generations, contradictions begin to appear, and new generations are required to adjust or modify practices from an earlier period as they adapt to new conditions.

To realize my goals of connecting current conceptualizations of writing praxis to that of the laboratory writing movement of the late 1800s, I have closely reviewed scholarship from 1887 through the late 1940s revealing how laboratory writing was first adopted by the field of composition. Here, I will begin to provide modern-day writing center practitioners with an interpretive history of writing center practices; what shaped them; through what contradictions they arose; what precipitated those contradictions; and what resolved them. In sum, I use CHAT to chart the movement of laboratory teaching from the composition classroom to that of the independent writing laboratory from which our current ideas of writing centers have emerged.

Defining a Practice

After Genung and Scott’s nascent laboratory approaches to composition instruction, the laboratory model reaches middle, secondary, and post-secondary institutions. In his 1894 article titled “Individual Teaching: The Pueblo Plan,” Preston W. Search, Superintendent of Schools in Pueblo, Colorado, departs from the current-traditional model by arguing that laboratory teaching should not aim to “consume time by entertainment, lecturing, and development of subjects; but to pass from desk to desk as the inspiring director and pupil’s assistant, with but one intent and that the development of the self-reliant and independent worker” (158). With increased student enrollment and large classrooms creating increasingly heterogeneous environments, laboratory instructional methods become a new tool for teaching composition during the early part of the writing center’s Formative Period.

Here, nurturing, student-centered, collaborative, and flexible environments function as tools in the new system of teaching: “Teachers are instructed to provide carefully for the discouraged pupil and to give more time to the lower half of the school, remembering that the bright ones may always be cared for by supplemental or advanced assignments of work” (Search 161). As a part of the emerging laboratory praxis, this philosophy is evidenced through some of the earliest laboratory work (Walker 1917; Horner 1929; “Organization” 1951) and remain as guiding principles for writing center work today. During the latter part of the nineteenth-century, writing instruction departs from a one-size-fits-all curricular model to one with laboratory practitioners developing students through one-on-one consultations or through students engaging in the work together.

Much like writing centers today, Search’s Pueblo Plan, one of the earliest examples of an emerging laboratory setting, predominantly furthers the laboratory teaching model by engaging a practical and active approach to learning focusing on the individual student: “The fundamental characteristic of the plan on which the schools are organized is its conservation of the individual” (Search 154). Thus, the Pueblo schools find employing a laboratory model, that is, a learning-by-doing methodology, develops a collaborative and flexible working environment for the individual student:

Every room is a true studio or workshop, in which the pupils work as individuals. The province of the teacher is not to line up the pupils and to consume time by entertainment, lecturing, and development of subjects; but to pass from desk to desk as the inspiring director and pupil’s assistant, with but one intent and that the development of the self-reliant and independent worker. (Search 158)

Making note of the basic structure of the laboratory setting, Search reveals contradictions existent in the current-traditional system where the “deeply communal motive” (Engeström “Activity Theory as a Framework” 964) of developing students’ composing skills loses coherence and meaning, for, in Genung’s words, a lecture-recitation framed course becomes a “bugbear” and drudgery (173). Importantly, however, identifying contradictions such as these also reveals how the new, experimental laboratory approach precipitates the future writing center movement.

For example, work in the Pueblo schools—an institution that focuses on the “love of work”—is not graded, and students only gain promotion on their ability “to do.” As such, the Pueblo schools engage student-centered efforts to encourage the work of individual students. Students work largely uninterrupted except during conferences with the instructor when guidance is needed, thus, co-mingling collaboration alongside flexible and student-centered approaches become part of the rules in the laboratory model. Here, students engage subjects at their own pace with “no assignment to-day [sic] of what shall be done to-morrow [sic]; if the teacher has any general working directions, they are given at the beginning of the working period” (Search 158). With the school’s focus on flexible, student-centered work, practices focus on motivating the student through the practicality of the classroom that provides “no recitation as generally conducted in schools” (Search 157). Such practices are reflected as rules in today’s writing center scholarship as Mackiewicz and Thompson argue that “motivation is both reflected in and enhanced by students’ active participation and engagement in learning and is particularly well supported in collaborative environments such as writing center conferences” (“Motivational” 39). With these practices beginning to take shape at the end of the nineteenth century, today, flexible, student-centered work and collaboration are cornerstones of writing center praxes.

Search’s Pueblo Plan also introduces the tool of record-keeping as another enduring principle of the laboratory model and mainstay of the writing center of today: the use of technology. In the Pueblo program, “the individual work is systematized, and a carefully kept record shows the advancement of the various pupils” (Search 159). While the work is student-centered, collaborative, and flexible, records become a form of technology that chronicles student work. Such documentation enhances the structure of the school’s laboratory plan and is essential in meeting the larger objective of developing students’ self-regulated work. Through the teacher’s careful instruction during one-on-one conferencing, each record keeps track of students’ successful completion of work and demonstrates the collaboration each student has engaged. It is this flexible and ingenious work that begins a course of record keeping that continues in writing centers today.

By adopting a laboratory methodology, the Pueblo schools cultivated the most formulated system of laboratory activity at the turn of the century, representing a course of curriculum exploration but also one rich for program analysis. Search’s article demonstrates the development of rules such as the guiding principles recognized in writing centers today: the work is student-centered, collaborative, and flexible with the use of technology being a central component of recording student work. Further, with Search’s workshop as a central scene of activity, we might also imagine how those rooms provide an environmentally sound space for the work in which students and faculty are engaged. While the particulars of the workshop studio space are not articulated, the Pueblo Plan roundly represents the rising movement of laboratory teaching in the public-school system of Colorado in 1894. With this, the movement continues in higher education as the academy continues to build upon the principles established thus far.

A Burgeoning System

Noting a continued boom in enrollment in 1895, Professor George E. MacLean declares in his article titled “English at the University of Minnesota” how “institutions of the New West . . . ‘stand for experiment, fertility of invention, and the broadening of standards’” (155). With ongoing movement away from a method of recitation and daily themes, part of the experimentation at the University of Minnesota includes developing instructional plans focusing on the interests of individual students:

If one term had to be used, the ‘laboratory method’ would describe ours. Indeed, the method has grown to such proportions that we have just been equipped with a literary laboratory. The English department is housed in an extensive suite of rooms in which are offices, seminary rooms, graduate workroom, and recitation rooms. These rooms are in the large new central library building just completed. The Departmental Library, especially classified to suit the work of the Department, will be distributed through these rooms. (MacLean 158)

This passage not only reinforces the developing laboratory teaching praxis in writing, but as a site for experimentation and fertility, the University of Minnesota initiates the future of laboratory teaching practices and writing center development by examining students’ needs. In doing so, the university builds upon the tool and guiding principle of considering environmental factors as part of laboratory work. However, MacLean’s laboratories also become one of the first examples of laboratories, or centers, placed in the campus library, thus enhancing tools and broadening the community available for instruction.

For freshmen, the instructor engages students as they undergo “constant practice in writing, constant attention to correct grammatical and rhetorical forms in speech, and thorough drill in the text-book” (MacLean 159). And for sophomore students, the focus on process continues with “the criticism of the student’s own work” (MacLean 160). While this may seem commonplace today, in 1895 it was surely a novelty. And for juniors and seniors in MacLean’s English Department, this practice, coupled with “the helpful criticism given by students to each other, applying general principles and noting progress in correcting faults,” helps develop student’s collaboration and self-assessment (161). Thus, with the continual development of the student, laboratory teaching ushers in the beginnings of writing center mentorship, for through the methodology of the laboratory classroom, students acquire skills for assessing their work as well as their peers’.

Though the two educational contexts differ, the setting at the University of Minnesota, like the Pueblo schools, functions as an environment where tools and subjects interact to engage the object, or objective, laboratory teaching pursues: the development of the self-reliant student. With student-centered, collaborative, flexible, and technological and environmental factors included as guiding principles, strategies established early in the developing laboratory praxis create an environment focused on developing self-reliant “students of investigation, thought, originality, and power” (Search 162). Additionally, the laboratory practices/experiments underway at the University of Minnesota demonstrate how laboratory practices begin developing and gaining definition. As the system builds momentum at the beginning of the twentieth century, the contributions of Search’s laboratory experiments and MacLean’s considerations continue to develop alongside other guiding principles as rules and tools become enduring components of the new system.

The Laboratory Teacher

A central component of the new order of laboratory teaching in composition characterizes the teacher not as a passive facilitator of instructional methods, but as one who engages each student on an individual basis: “Bright, attractive, and carefully prepared work and a warm-hearted, enthusiastic, co-operative teacher will always make the willing and energetic pupil” (Search 159). Here, Search’s Pueblo Plan establishes an enduring point for writing center consultants, for the success of laboratory methods and writing center practices largely depends on dynamic and well-qualified teachers to continue the expansion of laboratory teaching at the turn of the century. Accordingly, Search makes it known that “this method of work calls for strong teachers . . . The teacher cannot rely merely upon the preparation of the previous evening to meet the demands of the day. She must be equally ready on a hundred points” (169). Thus, not only must the laboratory teacher of Search’s era be informed, but much like the consultants of today, they must also possess flexibility in their approaches with individual students.

Further, from Los Angeles, California, Frances W. Lewis’ 1902 article “The Qualifications of the English Teacher” echoes this attention on the developed and flexible teacher. Lewis believes that “while the scientist must specialize, the English student who hopes to teach her specialty, must as far as possible make all knowledge her province” (19). If the object of the initial laboratory system is the development of a practical curriculum, the continually developing or evolving teacher becomes phenomenological as an outcome of the laboratory system’s activity. With laboratory teaching gaining momentum at the turn of the century, teachers and their abilities lie at the center of laboratory work with Lewis further arguing that the teacher “should also be a mistress of the art of questioning” (23). As a defining tool within the schema of laboratory teaching, this practice is still engrained in writing center practices today.[3]

As we see, then, the emerging dialectical system not only corrects itself to result in a new tool (laboratory teaching) to help subjects meet objectives of the system, but the system simultaneously recognizes the teacher (the conscious actor) as a dynamic cultural personality fundamental to laboratory teaching. In this role, the dynamic teacher passes “from desk to desk, assisting, quizzing, testing and qualifying students” (Search 158). In fact, this process is still at work today in many writing center contexts, furthering the student-centered principle to which writing centers adhere. Through the lens of CHAT, revealing contradictions “[gives] rise to those failures and [creates] innovations as if ‘behind the backs’ of the conscious actors” (Engeström, “Activity Theory and Individual” 32). In other words, through the earliest incarnations of the laboratory teaching movement, heretofore forgotten teachers like Search, Maclean, and Lewis play a central role in the development of the movement that, simultaneously, inform today’s practices through their identification of the laboratory teacher’s qualifications found in today’s laboratory and writing center praxis.

Additionally, at the National Education Association (NEA) conference in 1904, Philo Buck, Head of the English Department at William McKinley High School in St. Louis, Missouri, addresses attributes of the laboratory teacher. He begins his speech, “Laboratory Method in English Composition” from the Journal of Proceedings and Addresses of the Forty-Third Annual Meeting, with a charge for the teacher: “Speak as one with authority, but also as one who knows the heart and feelings of those he has in charge” (507). Mirroring earlier references to teachers as “inspiring directors” and “pupil’s assistants,” Buck’s language represents a direct indictment against faculty who resign to lecturing in large halls, engaging the uninspiring work of recitation, or combatting the “unmitigated bore” of theme work (Buck 507). While Buck strengthens his support for teachers, his assessment simultaneously advocates that teachers engage collaborative work as a flexible rule for the laboratory classroom in composition. He argues that themes should get “passed around the class by the pupils, and let the class criticize and correct each other’s work” (507). By no means are these revolutionary ideas today, but at the turn of the century, they represent a major shift toward adopting the flexible, self-evaluative, and collaborative strategies which we see in contemporary writing centers.

In addition to Search, MacLean, Lewis, and Buck’s work, Frances Ingold Walker demonstrates the prominence of the laboratory teacher’s role. From the New Trier Township High School in Kenilworth, Illinois, Walker, in her 1917 English Journal article, “The Laboratory System in English,” articulates the qualifications of the teacher: “The resourceful teacher possesses tact, sound judgement, a thorough knowledge of the individual needs of his pupils, and the ability to minister to those needs quickly and efficiently” (449). A teacher’s tools, and consequently, their praxes, mature. Thus, the scholarship from the beginning of the laboratory movement demonstrates how five guiding principles for laboratory work, and ultimately for future writing center work, have emerged.

Cultivating the Movement

During the early twentieth century (roughly 1919-1930) laboratory practices and our guiding principles continue to get honed particularly through the considerations of environmental factors and advancement and incorporation of technology in the classroom. These advancements demonstrate how writing laboratories, and writing centers of today, continue to evolve with each site incorporating environmental factors to provide students amenable space in which to work with the latest technological advances to accompany learning in those settings.

In 1919, in Scranton, Pennsylvania, for example, Central High School teacher Carl Zeigler’s classrooms began to adopt specific environmental and technological characteristics that augment students’ laboratory space. Features in many of the early writing labs such as Zeigler’s range from time-specific attributes such as “the most up-to-date pamphlets and volumes on social conditions, on democracy, and on the present war” to the décor of “comfortable chairs . . . arranged in a hollow-square formation . . .” (Zeigler 144-5). In early writing labs, students also had access to reflectoscopes, Victrola cabinets, and moving picture machines, all for use “under the wise guidance of the quiet, active teacher in charge” (Zeigler 145; Peck 753). Tools like these, which Ziegler infuses into his classrooms, are certainly part of our writing centers today, and with the development of the NCTE in 1911, we may see how the dissemination of information continues to spread (during the early part of the 20th-centeury as well as today). In turn, those dialectical contributions ultimately assist in developing rules and tools like those found in laboratory writing classrooms as educators and institutions continually adapt to changing student populations. . . much like we do today.

Additionally, with Zeigler’s work demonstrating early incarnations of Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC), for each class “is an English class” (Zeigler 145), the contradiction of lectures versus engaging students individually in laboratory settings and providing them time to write is mediated with writing in-session. First mentioned in 1912, the article “Can Good Composition Teaching be done Under Present Conditions?” by University of Kansas Professor Edwin Hopkins, argues “pupils should learn to write by writing” (2). For practitioners like Zeigler, the practice of in-session writing, both student-centered and collaborative, continues the work established by Search et al. In fact, with the tools of environmental and technological considerations unveiled by Zeigler, students do not passively receive information from a lecture; instead, they actively engage their own learning in consultation with the teacher.

With the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) providing more opportunities for collaboration after its development in 1911, Hopkin’s claim and Ziegler’s classrooms demonstrate how information sharing advances the laboratory movement at the beginning of the twentieth century and through today. For Hopkins and Zeigler, and many writing centers today, writing in-session is seen as compulsory, and with technology and environmental factors continuing to build onto previous models, guiding principles of laboratory work become solidified as part of the pedagogy. By the end of the 1920s, formal assessment of these practices and inquiry into how laboratory practices were working began.

Calibrating the Paradigm: Testing Assumptions

Around 1929, with laboratory teaching in practice for roughly 40 years, the laboratory classroom in composition encountered a contradiction of its own making as questions about its reliability and validity began to circulate.[4] At this time, Warren B. Horner carried out an experiment to assess the viability of laboratory teaching versus recitation methods. Identifying writing in-session and individual student records as central components of laboratory teaching methods, Horner’s assessment advocates the continuation of previous practitioners’ durable practices—our guiding principles. The practices Horner notes in his explanation of the laboratory movement demonstrate the practicality of the laboratory method as opposed to that of the recitation method. Thus, the experimental nature of the pedagogy and the development of tools, which we find so compelling today, continues in laboratory teaching’s evolution through the 1930’s.

For instance, Johns Hopkins University Professor Paul Mowbray Wheeler advanced the experimental nature of laboratory teaching in his 1930 article “Advanced English Composition: A Laboratory Course.” Through his work, Wheeler introduced student volunteers into the community component of the CHAT frame through his advanced course of English composition: “A member [of the class] should volunteer to act as a secretary for each meeting. He jots down what transpires and the most important criticisms which are brought out. Then these ‘minutes’ are filed and are available to any student who is forced to be absent or late” (558). As an early concept, these practices of note taking have not changed that drastically over the years. Today, consultants take notes to record what transpires during a session, thereby enhancing the technological resolve record keeping holds. These records, just as in Wheeler’s case, get filed so other consultants can see a students’ progress or assess a student’s areas of concern as each gets noted during a conference.

Through Horner’s and Wheeler’s experiments, the development of the laboratory classroom’s guiding principles, which are now rules and tools for the modern writing center, become further discernible. The experimental praxis must be student-centered; teachers offer flexible plans and possess flexible, nurturing qualities; collaboration is at the center of this student-centered and teacher-enhanced praxis; and technology and environmental factors play central roles in providing an atmosphere where work can flourish.

Expanding the System: A Model Writing Center from the Laboratory

In 1936, the laboratory, as it had been conceived for nearly 50 years, was described as a new and independent venture by the University of Minnesota General College’s Writing Laboratory’s first director, Francis S. Appel. As part of the General College, the Writing Laboratory at the University of Minnesota began as a voluntary course where students studied for an hour or two per week: “Composition as a subject is studied in the laboratory only when the student runs into difficulty writing things which he wishes to write in answer to natural demands” (Appel 71). Though Appel’s course was still a “course,” it was not an addendum to the composition course. In fact, with his method for administering activities, Appel’s course embodied the guiding principles culminated throughout the past 50 years of laboratory experiments and ultimately served as the blueprint of the modern-day writing center.

Appel claims that when students enter his lab, they “are told at the first meeting that they are to write anything they wish to, [and] the sudden freedom confuses them” (72). Under Appel’s direction, the laboratory adhered to a student-centered approach as he encouraged them to write about real situations that appeal to them. His approach is like starting over; he has to de-program students, and he does so with flexible, yet effective tactics further adding to the already growing resourcefulness of the laboratory teacher. Appel’s rules-based schema illustrates the intimacy offered in his lab, allowing the teacher to act as a model to transfer skills to his students. Thus, the flexibility and collaboration Appel offers in his lab engages students so they may more fully develop a genuine concern for their writing, and engage in self-evaluative work, thereby encouraging the continual development of the self-reliant student.

In-session writing and student revision—a staple practice in Appel’s laboratory—also becomes more prominent tool and rule for the student-centered philosophy for engaging students:

The only interruptions in [a student’s] work are those caused by his going to the bookshelves for a reference book or by the instructor’s sitting down with him for a brief conference about the work he is doing. And that is the time for a conference! More than half of the achievement of the writing laboratory, I am sure, can be attributed to the fact that conferences with the student take place when the student is writing. (75)

The practice of writing in-session, now recognizably a practice in circulation for over 20 years at the time of Appel’s article, helps define how learning opportunities “occur in a changing mosaic of interconnected activity systems” (Engeström, “Expansive Learning” 140). First realized in 1912, the activity system that introduces writing in-session now overlaps with the system of Appel’s Writing Laboratory.

Moreover, in this workplace environment where revision is key, Appel continued to enhance the presence of technology as an enduring tool in the lab as he added student files to the archive with multiple drafts collected, thereby constituting an early conceptualization of the portfolio, for “throwing away rough drafts constituted a major crime . . . Our files now contain, fortunately, many examples of careful, independent revision” (74). What started in 1887 as a collection of individual student work for the purposes of keeping track of student progress has now evolved into archival work allowing students to see their development through a portfolio-type file. Much like Wheeler’s work, this exercise also provides future students and teachers multiple opportunities to view examples at multiple points through which learning might occur.

Finally, Appel’s evaluation of his system also notes the multiple roles instructors play in the laboratory: “instructors in the laboratory try to tie in with the counseling system of the college” (75). As Muriel Harris discusses, in her 1980 article “The Roles a Tutor Plays,” the tutor may act as a coach, commentator, or a counselor. Thus, laboratory teaching specialists and today’s writing center consultants assess their practices while simultaneously cultivating the nurturing and flexible environments established throughout this beginning period of cultivating laboratory writing classrooms. Instructors in the laboratory must be able to determine how to engage each student, and they must be equipped to handle multiple situations as they arise. They become coaches, collaborators, and counselors, and they must be amenable to the work: “It is not . . . a method to be forced upon a staff, for the laboratory method requires enthusiastic and not mere perfunctory teaching by the instructors” (Appel 77). Noted throughout the Formative Period, Appel highlights the attribute of an enthusiastic participant as a prominent role of the consultant in the evolution of our writing center gestalt.

Conclusion

Offering an interpretation of ways in which guiding principles of writing center praxis have evolved, this article offers a view of writing center pedagogical beginnings. In 1940, at the end of the Formative Period, George Washington University (GWU) Professor Elbridge Colby’s article “‘Laboratory Work’ in English” demonstrates how the university adheres to the fundamental guiding principle of providing environmentally adequate space for their new writing laboratory. With technology readily available, the environmental characteristics of the library as a setting suitable for a writing laboratory are not coincidental. In such a setting, directed by knowledgeable teachers, in-session writing, collaboration, and a student-centered approach to developing self-sufficient writers opens the door to all university students. GWU’s expansion to include a writing laboratory in the new library precedes its future as an effort to build “close co-operation between the English and other departments of the university” (Colby 68-69). It is this interconnection of activity systems within the university that continues to develop and demonstrate a growing community of scholars looking to further develop laboratory practices at their institutions.

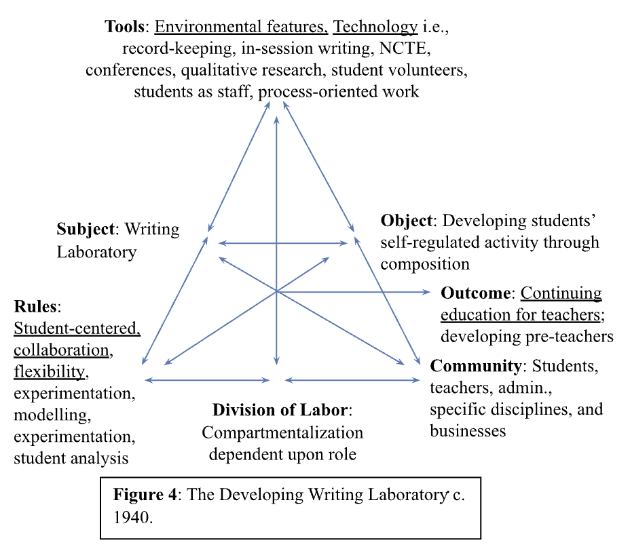

While variations exist in how laboratories function, Figure 4 exhibits the theoretical and environmental structuring of the writing laboratory at the end of the Formative Period, which is (almost) an exact model of writing center activity today. With the guiding principles underlined, mediating artifacts, or tools, have developed extensively over the previous 60 years with environmental factors such as tables and chairs in a well-lit room continuing to provide a relaxed environment where students can focus on the work at hand. Additionally, technology, a resource library, student files, empirical research, and the NCTE operating as an important information sharing tool have all added to the burgeoning laboratory system. Further, a student-centered approach and collaboration operate as rules for the system, and while this figure includes the continually developing teacher in the outcome, it is possible teachers, and their flexibility, may also get situated as rules or tools in the system. Laboratories have the same goals of developing self-sufficient students in flexible and nurturing environments; however, with the addition of student workers and the view that the lab may also act as a teaching lab for pre-teachers, the developing teacher becomes an outcome of the activity system developed by the end of the Formative Period.

In this setting, writing laboratories of the 1940s have the same goals of developing self-sufficient students in flexible and nurturing environments as our modern-day writing centers do; however, the new rationale of the next generation, 1940-1960, will threaten the existence of the model so fortuitously developed during this initial period. While the model ending the Formative Period is seen as progressive and fruitful, most resembling that which we see as writing center activity today, the next era viewed it as a bastardization of educational principles. The next generation will throw out most of our emerging guiding principles and usher in an agenda that will stratify and categorize an entire generation of students. “Remediation,” “prescription,” “remedy,” and other terms get injected into the new clinic model and leave a lasting residue that still taints many of our best efforts today. As a result, new contradictions emerge to throw the 1940s writing laboratory, and our current writing center archetype, into a regressive condition. Stay tuned for The Clinical Period.

nOTES

For more on Vygotsky’s original triad, see David Russell’s discussion of Activity Theory in “Activity Theory and Its Implications for Writing Instruction.”

The banking model of education is described by Paulo Freire in Pedagogy of the Oppressed: “Narration (with the teacher as the narrator) leads the students to memorize mechanically the narrated content. Worse yet, it turns them into ‘containers,’ into ‘receptacles’ to be ‘filled’ by the teacher. The more completely she fills the receptacles, the better a teacher she is. The more meekly the receptacles permit themselves to be filled, the better students they are. . . This is the ‘banking’ concept of education, in which the scope of action allowed to the student extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits” (52-3).

See, for example, Don Murray: “The Listening Eye: Reflections on the Writing Conference”; Joanne B. Johnson: “Reevaluation of the Questions as a Teaching Tool”; David Brooke: “Lacan, Transference, and Writing Instruction”; Isabelle Thompson and Jo Mackiewicz “Questioning in Writing center Conferences.”

From Elizabeth Boquet’s endnotes in “Our Little Secret”: “Horner's article summarizes the findings of his master's thesis, an empirical study which sought to compare the effectiveness of the laboratory method to the effectiveness of the lecture method. In the end, the results, which are fairly inconclusive, are far less interesting than his point-by-point explanation of the laboratory method” (57-58).

Works Cited

Appel, Francis S. “A Writing Laboratory.” Journal of Higher Education, vol. 7, no. 2, 1936, pp. 71-77.

Blunden, Andy. An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity, Haysmarket, 2012.

Boquet, Elizabeth H. “‘Our Little Secret’: A History of Writing Centers, Pre- to Post-Open Admissions.” The Longman’s Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice, edited by Robert W. Barnett and Jacob S. Blumner, Pearson, 2008, pp. 41-62.

Brooke, Robert. “Lacan, Transference, and Writing Instruction.” College English, vol. 49, no. 6, 1987, pp. 679-691.

Buck, Philo Melvin. “Laboratory Method in English Composition.” Journal of Proceedings and Addresses of the Forty-Third Annual Meeting Held at St. Louis, Missouri in Connection with The Louisiana Purchase Exposition. National Education Association, 1904, pp. 506-510.

Carino, Peter. “Early Writing Centers: Toward a History.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 15, no. 2, 1995, pp. 103-115.

---. “Open Admissions and the Construction of Writing Center History: A Tale of Three Models.” The Writing Center Journal, vo. 17, no. 1, 1996, pp. 30-48.

---. “What Do We Talk About When We Talk About Our Metaphors: A Cultural Critique of Clinic, Lan, and Center?” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, 1992, pp. 31-42.

Colby, Elbridge. “‘Laboratory Work’ in English.” College English, vol. 2, no. 1, 1940, pp. 67-69.

Davydov, Vassily V. “The Content and Unsolved Problems of Activity Theory.” Perspectives on Activity Theory, edited by Yrjö Engeström, Reijo Miettinen, and Raija-Leena Punamaki, Cambridge UP, 1999, pp. 39-52.

Engeström, Yrjö. “Activity Theory and Individual and Social Transformation.” Perspectives on Activity Theory, edited by Yrjö Engeström, Reijo Miettinen, and Raija-Leena Punamaki, Cambridge UP, 1999, pp. 19-38.

---. “Activity Theory as a Framework for Analyzing and Redesigning Work.” Ergonomics, vol. 43, no. 7, 2000, pp. 960-974.

---. “Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an Activity Theoretical Reconceptualization.” Journal of Education and Work, vol. 14, no. 1, 2001, pp. 133-156.

---. “Expansive Visibilization of Work: An Activity-Theoretical Perspective.” Computer Supported Work: The Journal of Collaborative Computing, vol. 8, no. 1, 1999, pp. 63-93.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin Books. 1993.

Genung, John Franklin. “The Study of Rhetoric in the College Course.” The Origins of Composition Studies in the American College, 1875-1925, edited by John C. Brereton, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995, pp. 172-177.

Grimm, Nancy Maloney. “New Conceptual Frameworks for Writing Center Work.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 29, no. 2, 2009, pp. 11-27.

Hopkins, Edwin M. “Can Good Composition Teaching Be Done Under Present Conditions?” The English Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, 1912, pp. 1-8.

Horner, Warren B. “The Economy of the Laboratory Method.” The English Journal, vol. 18, no. 3, 1929, pp. 214-221.

Lerner, Neal. The Idea of a Writing Laboratory, Southern Illinois UP, 2009.

Lerner, Neal. “Punishment and Possibility: Representing Writing Centers, 1939-1970.” Composition Studies, vol. 31, no. 2, 2003, pp. 53-72.

Lewis, Frances W. “The Qualifications of the English Teacher.” Education, vol. 23, 1902, pp. 15-27.

Mackiewicz, Jo and Isabelle Thompson. “Motivational Scaffolding, Politeness, and Writing Center Tutoring.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 33, no. 1, 2013, pp. 38-73.

MacLean, George E. “English at the University of Minnesota.” English in American Universities, edited by William Morton Payne, Heath, 1895, pp. 155-161.

Murray, Donald M. “The Listening Eye: Reflections on a Writing Conference.” College English, vol. 41, no. 1, 1979, pp. 13-18.

North, Stephen. “The Idea of a Writing Center.” College English, vol. 46, no. 5, 1984, pp. 433-446.

“The Organization and Use of a Writing Laboratory: The Report of Workshop No. 9.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 2, no. 4, 1951, pp. 17-19.

Peck, Juanita Small. “The English Laboratory.” The English Journal, vol. 23, no. 9, 1934, pp. 751-764.

Russel, David. “Activity Theory and Its Implications for Writing Instruction.” Reconceiving Writing, Rethinking Writing Instruction, edited by Joseph Petraglia, Hillsdale, 1995, pp. 51-78.

Scott, Fred Newton. “Michigan English.” The Origins of Composition Studies in the American College, 1875-1925, edited by John C. Brereton, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995, pp. 177-181.

Search, Preston W. “Individual Teaching: The Pueblo Plan.” Educational Review, vol. 7, no. 2, 1894, pp. 154-170.

Thompson, Isabelle and Jo Mackiewicz. “Questioning in Writing Center Conferences.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 33, no. 2, 2014, pp. 37-70.

Walker, Francis Ingold. “The Laboratory System in English.” The English Journal, vol. 6, no. 7, 1917, pp. 445-453.

Wheeler, Paul Mowbray. “Advanced English Composition: A Laboratory Course.” The English Journal, vol. 18, no. 7, 1930, pp. 557-566.

Ziegler, Carl W. “Laboratory Method in English Teaching.” The English Journal, vol. 8, no. 3, 1919, pp. 143-153.