Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 10, No. 1 (2012)

CHARACTERIZING SUCCESSFUL "INTERVENTION" IN THE WRITING CENTER CONFERNCE

Sam Van Horne

The University of Iowa

sam.vanhorne@gmail.com

In the January/February 2012 issue of the Writing Lab Newsletter, Bird writes about specific ways to examine the concept of deep learning and how these concepts are suited to the work of writing centers. In arguing that writing centers can contribute to students’ cognitive development, Bird states, “By rethinking our view of learning to include not only concepts and skills but also thinking processes, we expand the learning potential in writing center work” (1). Attention to learning has, for decades, been of paramount interest to writing center scholars who envision the writing conference as a site for student learning. Scholars have frequently addressed how peer tutoring could promote successful student learning. For example, many (if not all) writing center practitioners can recite North’s adage about how writing centers should “produce better writers, and not better writing” (“Idea” 438), but perhaps fewer are familiar with his other writings in which he is more specific about the role of tutors. In “Training Tutors to Talk About Writing,” North writes, “tutoring writing is … intervention in the composing process” (434). And in “Writing Center Diagnosis: The Composing Profile,” on the benefits of research in the writing center, North states, “[W]e are able to address our students’ writing processes directly and systematically, to move from informing students about writing to meddling with how they write” (42).

It is a sign of a healthy academic discourse that many writing center professionals have been endeavoring to explore and characterize the nature of successful “interventions.” And yet, reading these works gave me pause: how could I reconcile writing center pedagogy, with its emphasis on empowering students to make decisions in the writing process, with terms like “intervention” and “meddling”? The polar opposite of this approach might be the strategies advocated by those who have championed nondirective tutoring methods, such as Brooks, who argues that tutors should mimic a student’s disinterest in a writing tutorial with a similar show of disinterest.

But there is a way for writing tutors to provide an effective structure for writing center tutorials that lies between extreme nondirective tutoring and prescriptive, directive writing tutorials. This strategy is grounded in the framework of Vygotskian theory that has already been cited by writing center professionals. Bruffee cites the work of Vygotsky when describing the nature of collaborative learning: “In learning, there is always another person—or several other people—directly or indirectly involved” (137).

Although some writing center researchers have used Vygotskian theory to provide explanations of effective peer tutoring, relatively few have drawn upon the concept of the zone of proximal development (ZPD) and its more recent developments (such as situation definition) that have contributed to the understanding of how learning happens in the ZPD. In this article I intend to describe how the ZPD and the neo-Vygotskian conception of situation definition provide a sound theoretical framework for promoting student learning in writing center conferences, describe strategies grounded in this framework, and briefly discuss examples of how situation definition plays a role in writing center conferences.

Review of Literature About Vygotskian Theory in Writing Centers

With its emphasis on promoting the development of learners, the ZPD provides an effective framework for a writing center conference. Vygotsky defined the ZPD as the “distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (86). According to this perspective on learning, the proper object of instruction is those “functions that will mature tomorrow but are currently in an embryonic state” (Vygotsky 86). It is vital, then, for a tutor or instructor to keep the students working at the limit of what they can do alone. According to Vygotsky, “the notion of the zone of proximal development enables us to propound a new formula, namely that the only ‘good learning’ is that which is in advance of development” (89).

The original definition of the ZPD complements writing center pedagogy in that it refers not to tasks, but to levels of development (Chaiklin). Indeed, Gillespie and Lerner emphasize that while editors “focus on the text,” tutors “focus on the writer’s development and establish rapport” (45). Thus, the real power of this framework is that it provides a structure for considering how to facilitate an interaction that helps a writer develop a better writing process or a better conception of rhetorical strategies that implicitly guide the writing process. If the ZPD were merely a theory about helping people finish tasks, without considering their conceptions of the writing process, the activity in a writing conference would just be feedback or editorial help.

Vygotskian social constructivism and the more recent advancements in this theory of learning and development provide special tools to peer tutors in writing centers (Vygotsky; Wertsch Vygotsky; Wertsch “The Zone”). Writing center theorists have drawn upon Vygotskian social constructivism in their descriptions of effective peer tutoring. For decades, writing center researchers have emphasized the social nature of learning in writing center interactions (e.g., Bruffee; Lunsford; Murphy). Bruffee, for example, cites the work of Vygotsky in arguing that tutorial conversation can result in a student developing a better way of thinking about a topic or the writing process.

In that sense, advocates of nondirective tutoring can find the framework of the ZPD to be useful because of its emphasis on the development of the learner through social interaction. This emphasis is central to the Vygotskian model in that students, as the primary agents of the writing center tutorial, determine goals for their development, and the role of the writing tutor is to provide scaffolding that is only necessary to the extent that the writer needs explicit assistance. Tutors then fade, using discourse strategies (such as abbreviated speech and open questions) that promote student ownership of the activity in the tutorial.

Some writing center scholars have drawn connections between so-called directive tutoring and elements of Vygotskian theory. Shamoon and Burns argue that directive tutoring can be a powerful strategy that involves inviting students to learn from a tutor through a process of observation and emulation. Indeed, Shamoon and Burns argue, “Directive tutoring displays rhetorical processes in action” (146). Such activities bring hidden writing processes out in the open, which a student can practice with a tutor as he or she engages in learning in the ZPD. These activities can result in effective student learning: “This cognitive shift seems to depend upon observation and extensive practice—often in emulation of the activities of the tutor-expert—leading to the accumulation of expert repertoires and tacit information” (Shamoon and Burns 143). In a discussion about why some students found directive tutoring to be so helpful, Clark and Healy argue that “directive tutoring is consistent with Vygotsky’s concept of ‘the zone of proximal development’” (38). They go on to argue that directive tutoring is helpful when the process engages the development of students and helps them to complete a task (e.g., plan a successful revision) that they could not do alone. Although some advocates of nondirective tutoring may claim that directive tutoring could prevent students from succeeding in their writing activities, Thompson et al. found that students in the writing center preferred interactions in which tutors structured a tutorial about an aspect of writing that the students were able to select.

Applying the ZPD and Situation Definition in Writing Center Tutorials

Scholars have expanded upon the work of Vygotsky and have helped develop conceptions, which are grounded in social constructivism, that are useful to those involved in writing center work. For example, these scholars—having recognized that Vygotsky did not expand upon how a learner traverses the ZPD—explored the ways in which tutors can facilitate student-centered interactions that promote student development. These new insights provide the framework for facilitating interactions that take into account a student’s level of development as well as specific discourse strategies that a tutor may implement during a writing conference. These strategies can help ensure that the activity in the ZPD is productive and results in new strategies that the student may use after the writing conference.

One of these concepts is situation definition. According to Wertsch (“The Zone”), “A situation definition is the way in which a setting or context is represented—that is, defined—by those who are operating in that setting” (8). In this perspective on activity in the ZPD, a tutor and learner may have two different conceptions of what is happening in an activity. Wertsch (“The Zone”) provides an example of two separate activities in which two children are building a shape out of blocks that is a copy of a model. One child consults the model in the activity, but the other child does not. Although both children are engaged in the same activity, they have different notions of what the purpose of the activity is, which in turn affects how they carry out the action. The goal in this situation is to structure an activity that helps the one child who is not using the model to begin consulting the model and build a copy. Thus, according to Wertsch (“The Zone”), learning in the ZPD is a process of “situation redefinition,” in which a learner develops a qualitatively different situation definition than the one he or she had at the beginning of the encounter (11). This complements the overall goal of many writing centers: that their students develop new attitudes toward writing and new psychological tools to use in the writing process.

There are different ways in which a tutor can promote situation redefinition, but one important concept that must be considered at the outset of a tutorial is establishing intersubjectivity. A peer tutor and student achieve intersubjectivity when they have the same situation definition of the interaction and, importantly, know that they share the same situation definition (Wertsch “The Zone”). In the beginning of a writing conference, a peer tutor can elicit a student’s definition of rhetorical concepts that are important to the writing task at hand. For example, a student who says that a conclusion “wraps up the paper” may be able to benefit from a more nuanced definition that he or she can use in academic writing.

A student’s answer (as in the example in the previous paragraph) corresponds to his or her actual level of development—the current conception that implicitly guides a student’s writing process. A peer tutor can then use this information to plan a student-centered writing conference that can help the student develop a more mature definition of a rhetorical concept or writing strategy for the task at hand. In an attempt to establish intersubjectivity and promote effective communication in the writing conference, a peer tutor may temporarily adopt the student’s situation definition in an activity that has the goal of helping the student progress and consider rhetorical concepts more critically. For example, the peer tutor may first ask questions about this situation definition such as “Can a conclusion do anything else besides ‘wrap up’ the ending?” This adoption of a temporary situation definition, which is closer to the student’s current level of development, enables the peer tutor to begin helping the student develop a more nuanced definition.

To promote situation redefinition, peer tutors may help students to make more context-informative expressions in which they use writing terminology in the specific context of their own work (Wertsch, Vygotsky). The conversation moves beyond abstract definitions of rhetorical concepts toward descriptions of how a certain rhetorical concept functions within a student’s writing. Context-informative expressions can be reflective of how students use the psychological tool. And these context-informative expressions could be supplemented with an activity in which, perhaps, a student practices writing a different conclusion and explaining its role more specifically in the text.

When peer tutors and students collaborate in an activity that promotes situation redefinition, this new definition must be within the student’s potential level of development, which may or may not be similar to the peer tutor’s actual level of development. This takes into account the need to set a concrete, realistic goal for a writing conference.

How does a peer tutor know exactly how far a student can progress in a writing conference? Interaction in the writing conference establishes this knowledge. As a student progresses in the writing center conference, using more context-informative expressions to describe exactly how a rhetorical concept functions in his or her writing, the peer tutor may begin to use more abbreviated speech, which is characteristic of interactions in which interlocutors have achieved intersubjectivity. In using more context-informative expressions, a student can, for example, move beyond describing “conclusion” or “argument” in abstract terms and describe how they function within the specific piece of writing. These context-informative expressions can be a signal that the student is progressing through the ZPD and internalizing an idea that he or she could not explain in specific terms.

Students and peer tutors may also have different situation definitions of the conference interaction. For example, a peer tutor who is meeting with a student who only wants editing help may discuss the situation definition of the conference interaction. For this reason, a period in a writing conference is often devoted to discussing the purpose of the writing center and what the peer tutor’s role will be in helping the student to develop skills that he or she can apply not only to the paper or project in question, but to future academic writing projects.

In the following research study that I conducted at a college in the Midwest, I examined how writing center consultants (what peer tutors were called at the institution) promoted situation redefinition in writing center conferences. The Institutional Review Board at my university approved all research procedures, and I assigned the participants pseudonyms to protect their anonymity. I observed, recorded, and transcribed each writing conference. After the conference, I collected copies of the student’s conference draft and written notes. I then interviewed the writing consultant to learn about his or her decision-making process during the writing conference. Upon completing the writing project, each student sent me a copy of the final draft and participated in a debriefing interview about the revision process.

To analyze students’ revisions, I labeled and coded each revision according to the taxonomy developed by Faigley and Witte. The taxonomy includes two main categories of revisions: surface and textual. Surface revisions include edits to grammar and spelling as well as meaning-preserving revisions that are, for the most part, synonymous to the text that was replaced. Textual revisions comprise microstructure revisions, which alter the meaning of a local section in a piece of writing, and macrostructure revisions, which change the overall meaning of a text. To analyze the field notes, interview transcripts, and reflections, I sorted the data based on salient themes and coded the data in Atlas.ti to conduct cross-code analysis to determine the relationships between writing conferences and students’ revision processes. To ensure reliability, a co-researcher participated in the initial data analysis, the development of definitions for the codes, and the early stages of the coding process.

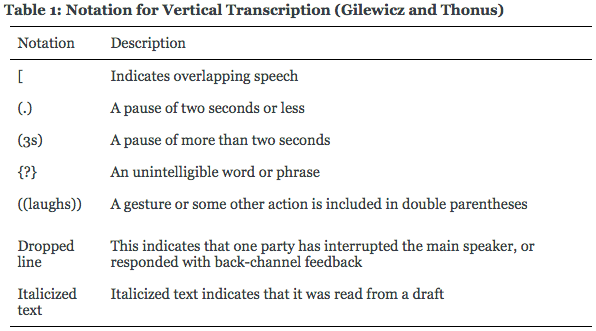

As part of this study, I examined a writing conference between two writing consultants and another between a student and a writing consultant. A full examination of the interactions in these writing conferences is outside of the scope of this article, so I include these examples to illustrate the concept of situation definition in writing center conferences. I used vertical transcription to capture the paralinguistic features of writing conference conversation (Gilewicz and Thonus). Table 1 includes the notation for vertical transcription.

In the following excerpt, Alicia was in the role of peer tutor and Brynna was the writer. Brynna had written a short nonfiction essay based on the death of an uncle, but had difficulty adhering to the 300-word limit. She had written this assignment for her class on writing center pedagogy (a staff-development course taught by the writing center director), and she was supposed to have a writing conference with a senior writing consultant.

Being part of the same community of peer tutors, Alicia and Brynna had similar viewpoints on the purpose of a writing conference and had likely learned similar techniques for prompting students to revise their writing. In this case, Alicia asked Brynna whether she had done a specific activity to reduce the length of her writing. They communicated efficiently because of their similar situation definition of a writing conference and their shared knowledge of writing processes that are useful for different situations. Their conversation suggests that they both know of a word-cutting activity. In addition, in the interviews that I conducted separately with both participants both indicated they liked to spend extensive time revising. Alicia (even though she claimed to be an environmentalist that hesitated to waste paper) said that she enjoyed interacting heavily with her own writing by marking up paper drafts, and Brynna also spent time marking up drafts after a writing conference to help her decide how to proceed with revising her work.

Alicia and Brynna continued to discuss the main ideas in the writing conference. In the interviews I conducted with them after the writing conference, I learned that they had very similar attitudes toward writing centers and writing center conferences. About the main reasons she liked to have conferences, Brynna said, “I really like the idea of the re-vision, like you’re re-seeing your paper through somebody else’s eyes and they may not know the subject either, which is, like, even better for you because they’ll have more questions.” And Alicia said that her goal for the writing conference was “to just like help her like nudge her way into what her final version was gonna be which is, you know, something that was far more complex than what she’d put out, put down in the paper right away.” It was this intersubjectivity that may have enabled them to have a productive conversation in which Brynna welcomed questions about her writing and participated equally, without “yes” or “no” responses that can be indicative of a lack of interest in the writing conference.

But what kind of learning happens when a peer tutor and writer already share a similar situation definition of rhetorical concepts or of the writing conference? How, according to the Vygotskian framework of learning, can one peer tutor facilitate an activity in which another peer tutor expands his or her current level of development? This question, admittedly, poses a problem to a method of tutoring that is grounded in the concept of situation definition and the ZPD. In this case, a peer tutor like Alicia may help a fellow peer tutor to apply writing strategies in different rhetorical situations or use them in a more nuanced manner.

And what happens when, as is often the case, the writing consultant and student have different situation definitions of the purpose of the writing center conference? In the following example, a peer tutor (Nancy) has read entirely a paper written by the student (Janelle), who believes that she will receive editing help at the outset of a writing conference. Nancy believed that she should first discuss the main ideas and then proceed to discuss errors in mechanics. In this excerpt, she imposes her situation definition of a writing conference at the outset and makes explicit her reasons for avoiding talking about sentence-level problems in Janelle’s writing.

A method of tutoring that is grounded in these principles of learning theory does not suggest there is only one “definition” of a rhetorical concept (or some other idea) that students can learn and thereby master the writing process. This method complements nondirective tutoring strategies in that there is no assumption of only one correct situation definition that the student must develop. Rather, these definitions are contextualized and particular to the discourse community in which the student is participating. Thus, methods of tutoring that are grounded in the concept of situation definition should include strategies for helping students recognize how different rhetorical concepts may be applied in a variety of contexts.

Assessment and Tutoring Based in the Framework of the ZPD

This framework can also point toward effective assessment practices for writing conferences and peer tutoring. If the proper focus of assessment should be the development of the writer, an assessment process can also be grounded in learning theory that is student centered and oriented toward the development of students’ writing processes. For example, during the agenda-setting phase of writing conferences, peer tutors can ask students to define the concepts that are at the heart of the writing conference. Then, at the end of the writing conference, the peer tutor can ask the student to re-define the concept. A difference in definitions may reveal just how far the student was able to progress in terms of developing a better concept to use in the writing process.

In addition to assessment that is centered on how students can define rhetorical concepts or other concepts related to their writing processes, this framework provides a basis for assessment that happens in the dyadic pair of the peer tutor and student. Writing center conferences can uncover and examine the “maturing functions” that activity in the ZPD can elicit (Chaiklin 52). These maturing functions may be the abilities that are essential to succeeding in academic writing, but cannot be observed (yet) in solitary activity. Chaiklin argues, “Successful (assisted) performance can be used as an indicator of the state of a maturing psychological function” (53).

Conclusion

In looking toward new methods for writing centers to promote student learning, I propose that writing center administrators and tutors alike consider examining the theories of Vygotsky and of the neo-Vygotskian researchers who have expanded upon Vygotsky’s ideas. Writing center tutors can ground their writing-conference strategies in sound learning theory by seeking to helping students to achieve situation redefinition of rhetorical concepts. Thus, a writing tutor can carry out North’s effective “interventions” (“Training”) but avoid appropriating the student’s writing or focusing solely on correcting the text at hand. These new situation definitions can then establish students’ capacities to develop and apply new writing processes for successful revision.

Works Cited

Bird, Barbara. "Rethinking Our View of Learning." The Writing Lab Newsletter 36.5-6 (2012): 1–6.

Brooks, Jeff. "Minimalist Tutoring: Making the Student Do All the Work." The Writing Lab Newsletter 15.6 (1991): 1–4.

Bruffee, Kenneth. "Peer Tutoring and the ‘Conversation of Mankind.’" Writing Centers: Theory and Administration. Ed. Gary Olson. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English, 1984. 3–15.

Chaiklin, Seth. "The Zone of Proximal Development in Vygotsky's Analysis of Learning and Instruction." Vygotsky's Educational Theory in Context. Ed. Alex Kozulin, et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. 39–65.

Clark, Irene, and Dave Healy. "Are Writing Centers Ethical?" WPA: Writing Program Administration 20.1/2 (1996): 32–8.

Faigley, Lester, and Stephen Witte. "Analyzing Revision." College Composition and Communication 32.4 (1981): 400–14.

Gilewicz, Magdalena, and Terese Thonus. "Close Vertical Transcription in Writing Center Research." The Writing Center Journal 24.1 (2003): 25–50.

Gillespie, Paula, and Neal Lerner. The Longman Guide to Peer Tutoring. 2nd ed. New York: Longman, 2008.

Lunsford, Andrea. "Collaboration, Control, and the Idea of a Writing Center." The Writing Center Journal 12.1 (1991): 3–10.

Murphy, Christina. "The Writing Center and Social Constructionist Theory." Intersections: Theory-Practice in the Writing Center. Ed. Joan Mullin and Ray Wallace. Urbana: NCTE, 1994. 161–171.

North, Stephen. "Training Tutors to Talk about Writing." College Composition and Communication 33.4 (1982): 434–41.

---. "Writing Center Diagnosis: The Composing Profile." Tutoring Writing: A Sourcebook for Writing Labs. Ed. Muriel Harris. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman and Co., 1982. 42-52.

---. "The Idea of a Writing Center." College English 46.5 (1984): 433-46.

Shamoon, Linda, and Deborah Burns. "A Critique of Pure Tutoring." The Writing Center Journal 15.2 (1995): 134-51.

Thompson, Isabelle, et al. "Examining our Lore: A Survey of Students' and Tutors' Satisfaction with Writing Center Conferences." The Writing Center Journal 29.1 (2009): 78-105.

Vygotsky, Lev S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978.

Wertsch, James V. Vygotsky and the Social Formation of Mind. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985.

---. "The Zone of Proximal Development: Some Conceptual Issues." New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 1984.23 (1984): 7-18.