Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 14, No. 1 (2016)

"I CANNOT FIND WORDS": A CASE STUDY TO ILLUSTRATE THE INTERSECTION OF WRITING SUPPORT, SCHOLARSHIP, AND ACADEMIC SOCIALIZATION

Amy Whitcomb

amyawhitcomb@gmail.com

Introduction

I was hired at my current institution to build writing support for graduate students. I hold the title Instructional Consultant and work in the campus Writing Center, which is part of Academic Affairs. Two and half years ago, when I entered this job, I considered myself well prepared for interacting with graduate students and their writing: I had been a writing tutor for graduate students at two other universities, worked as an editor at two interdisciplinary research journals, and experienced three graduate programs myself, spanning an R1 institution, a natural sciences program and a fine arts program, and both decamping and graduating. Yet the service I provide in my current position is not what I expected to offer; I was not fully prepared to support these graduate students in these kinds of graduate programs. It occurs to me now that there’s perhaps no way I, or any incumbent, could have come ready to resolve the gaps in service and support for graduate student writers at this institution and others like it. This essay aims to illustrate the lived experience at the intersection of writing, student, tutor, professor, and graduate school. With a close description and analysis of one representative student, writing project, and student-tutor relationship, the essay approaches an answer to What kinds of support do graduate student writers from underserved populations need and want, and how does it compare to the kinds of support students are currently getting? The essay invites further inquiry into how support, scholarship, and academic socialization interrelate for students and academic support staff.

The university where I work is a 25-year-old urban public university affiliated with a large, research-based “mother” campus thirty-five miles north. In 2015, approximately 690 graduate students were enrolled in twelve Master’s programs and one Ph.D. program. Recall the characteristics of the universities where I had studied and worked, mentioned above. This institution is none of them: It is not R1. It does not offer a graduate degree in any natural or physical science nor in any fine art. More striking is the fact that most graduate students here do not write theses or dissertations. They complete alternatives, named variously across departments as a culminating paper, a capstone paper, a capstone project, or a scholarly project proposal. After familiarizing myself with this information as a new employee, I wondered: so what makes these “graduate” programs—and the students within them “graduate” students? At a fundamental level, the students are graduate students because they hold Bachelor’s degrees and they seek academic opportunities to progress in their professional lives. These are the root (the minimum qualifications) of any graduate student; these students happen to have or want professions outside of academia. Traditional notions of scholarship may be wholly incidental to their aspirations. Indeed, my institution is an urban-serving university with a stated mission to promote and enact change in our community. This institution is one of thirty-five members in the Coalition of Urban Serving Universities and countless other institutions of higher education or select programs within them that offer practice- or credential-oriented education in degree tracks. Most of our graduate students pursue Master’s degrees in social work, nursing, urban studies and geographic information systems, cybersecurity, business, education, and computer science.

Nearly twenty-five years into its operation and offering of Master’s degrees, the institution where I work has no centralized graduate student support. To solicit information from or share information with graduate programs, I make individual contacts with the Graduate Advisors Council, the group of program-based academic advisors for graduate students; faculty who teach graduate courses; our student staff of writing tutors, some of whom are graduate students; librarians; administrators in the Graduate School at the main campus; and graduate students themselves. Needless to say, information among these stakeholders is not shared seamlessly, consistently, quickly, or at all. I feel for the graduate students who, finding themselves in a conflict or conundrum, know only of their immediate professors and their one academic advisor as go-to support.

I feel for those students, in part, because I encounter a similar void of support network myself among my professional peers. In the Chronicle of Higher Education as well as a dozen of the journals most relevant to my field (e.g., Praxis, WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, Writing Center Journal, College Composition and Communication), and on the ever-expanding and ever-welcoming Consortium on Graduate Communication website (https://gradconsortium.wordpress.com), I find articles about dissertation boot-camps and adapting chapters into publishable articles and negotiating relationships with principal investigators or lab technicians and putting statistics into plain language and any number of other insightful and practical conclusions that leave my university’s kind of graduate students out. Although the area is growing, there is currently very little research that addresses graduate students who do not aspire to academic careers. Faculty, including those at my university, can hardly offer other perspectives; to secure their positions, they come with doctorates, publications, and patents-based traditional methods of original scholarly research. I’m not saying they are no help to me in building writing support for their students—they are, as the case study I offer in this article will demonstrate—but they often cannot speak to the practitioner’s or professional’s culture shock upon re-entering academia. For a time, I couldn’t either. In consultations with students, my comments couched in explanations of “hypotheses” or “statistical significance,” “replication” or “committees” seemed irrelevant at best, unintelligible to students at worst. If my work is not to help budding scholars develop as scholarly writers, then what is it?

Consultations

In the spring of 2015, at the Writing Center, I reviewed the culminating paper of a graduate student in the Masters of Nursing (MN) program. I’ll call her Stacy. Stacy was representative of our graduate students in her status both as a primary speaker of a language other than English (her primary language is Spanish) and a mid-career professional. Parts of her paper described her long history as a practicing nurse, and I came to learn that graduate school was a pragmatic move for her, not something which she previously envisioned herself doing or prepared for with deliberate inquiries, networking, post-bac classes, or other forms of acculturation/socialization. She did not mention any plans to pursue the Doctorate of Nursing Program at our main campus upon graduation.

Stacy was a representative graduate student of ours, and her writing basically representative of our graduate-level English-language-learning professional students. Our sustained interaction through writing consultations is not entirely representative of my interactions with graduate students here. I meet with many graduate students both in person and online (asynchronous eTutoring using Microsoft Word comments and Track Changes); with Stacy, we used only eTutoring. Many graduate students and I meet two or three times a quarter, but Stacy and I worked together ten times over the ten-week quarter. Some graduate students come with concerns about only one section of their writing project (such as literature review or references page) or concerns about only one aspect of writing (such as grammar or transitions); Stacy hoped for higher and lower concerns to be reviewed and revised by me throughout her paper. Still, Stacy will not be my last student with such needs and provisions, nor is her situation, I believe, unique among her peers in other academic programs or institutions.

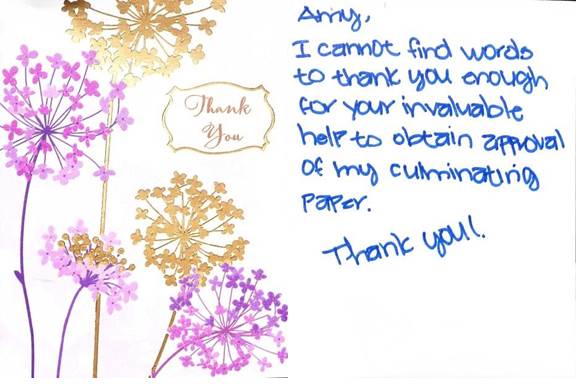

Here I offer my record of our correspondence and writing-related comments to chronicle the relationship between graduate student and university staff member working through writing support. To provide perspective and breadth, I offer two conventional data sets and two unconventional qualitative data sets. The data are a list of Stacy’s writing concerns for each draft, as documented in our appointment scheduling system; a count of writing topics that I commented on for each draft; an email between Stacy’s major professor and myself; and a note Stacy delivered to my office at the end of the quarter.

Over the course of six weeks, I read and provided feedback on ten drafts of Stacy’s culminating paper. According to the nursing program’s website,¹ “the culminating paper for the MN coursework option” guidelines are the following:

Describe in detail the two additional courses taken, how these courses enabled the student to meet one or more of the curriculum option learning outcomes and one or more MN program goals

Explain how the coursework reflects scholarly inquiry activity (e.g., what research was conducted? What evidence was acquired? Was a concept analyzed or researched? Were evidence-based best practices identified?)

Describe how coursework will be integrated with future professional goals

Stacy’s first draft with me was approximately 1,500 words. Her tenth draft was approximately 3,000 words. Each writing consultation occurred asynchronously online and lasted fifty minutes. Stacy uploaded a draft to her online appointment and used the appointment scheduling system to write me a note updating me with her wants and needs for that session. I returned each draft with a headnote describing my overall observations of the writing and up to thirty-six comment bubbles in the document’s margins. I did not use Track Changes to write directly into her text on any draft. The table below shows our online correspondence through the scheduler system notes, the headnotes, and the comment bubbles. It compares Stacy’s requests with the number of comments I made to address those requests and other comments to further the writing process and support the writer’s development.

Not revealed in the table is the fact that each request for help from Stacy included at least one expression of gratitude (usually “thank you” or “thank you again”) and each headnote from me began encouragingly by identifying the revisions and current strengths of Stacy’s writing and mindset. We had friendly conversation and developed a friendly relationship. I’m glad that I offered the positive reinforcements that I did, in headnotes and marginal comments, because I was not privy to any encouraging remarks from her other readers (i.e., professors).

The data in the table demonstrates that Stacy and I were both bouncing around the common writing tutoring hierarchy. Looking back at this work of mine from last year, I’m surprised and ashamed that I addressed subject-verb agreement, for example, in the first draft, for writing mechanics appear far down on the hierarchy. My approach makes sense to me now only within the context of how I phrase my marginal comments. My comments about subject-verb agreement would say something like “It’s unclear to me how many people you’re talking about here because the subject (noun) and corresponding verb don’t ‘agree’ in number. Agree in number means . . . ”—thereby connecting an issue with mechanics to Stacy’s concern about “clarity.” In other words, many of my comments addressing lower-order concerns are couched in language that conveys how important they are (i.e., not lower) in making one’s points accurately and precisely for the readers’ benefit. Still, given my habit of writing marginal comments to include observation from a reader’s perspective as well as explanation and exemplification—and my use of scaffolding and prioritizing error patterns over singular mistakes or typos—my comments seem to have run the gamut. This demonstrates the vast breadth and depth of support requested by a graduate-level English-language-learning professional student and the vast knowledge base and time required by the tutor to meet those requests.

Our volleying among concerns exhibits a kind of frenetic energy. Stacy was spurred to use the Writing Center by her professor. I had met the professor in another context and worked with other undergraduate and graduate students of hers for various assignments. Both Stacy and I understood that grammar and stylistic conventions were important to the professor. Even so, Stacy’s initial request for “final review” and subsequent requests for everything from sentence structure to margin spacing to “does it make sense?” suggest, to me, a lack of vision for and authority over her writing. I’ve witnessed low confidence in multilingual students writing in their target language—they feel like they just can’t know enough vocabulary or syntax to sound smart. Stacy displayed low confidence, but she also had challenges understanding the purposes that a culminating paper would serve for her as a graduating Master’s student. She sometimes titled the document “cumulating paper,” which could equally hit the purpose but was not, in fact, the accurate spelling or academic intent. I argue that the bulk of our interaction was rooted not in language use per se but in lack of academic socialization. I was working to explain linguistic concepts, genre conventions, process techniques—and scholarly objectives. What does it mean to do research? In singular, contextualized comments, I was probing Stacy to consider and articulate why and how research is important to her professional trajectory.

Correspondence

After five consultations, I contacted Stacy’s major professor with concerns about possibly “overstepping” my role and infringing on their student-professor relationship. I begin with my email to the professor. The excerpts show the risk I took in losing the trust of the student and the confidence of the professor to learn what more—what more?—I could do to send a competent and confident writer into the world after her eight quarters of graduate school. I follow up with the professor’s reply. When the professor says, “Stacy is getting the same type of comments from multiple sources,” I interpret that as an acknowledgement that our writing center and our institution believe in the power of communication and could be doing more to make a comprehensive networked or centralized support system for graduate students. When the professor says, “Much of these [suggestions] she has to come to herself,” I interpret that as both honoring and neglecting the process of academic socialization. It honors the developmental, individualized, and autonomous nature of learning. It neglects the directive, instructive nature of learning. In the professor’s email reply, I did not find an advocate for examining the socialization needs of our graduate students. This correspondence shows one promising, yet emotionally trying and labor intensive, way I’ve reached out for more guidance on supporting graduate-level English-language-learning professional students.

Tutor’s Email to Professor

From: Amy A. Whitcomb

Sent: Friday, May 8, 2015 4:39 PM

To: [Professor]

Subject: TLC consultations with MN student

Dear Dr. [Professor],

I’m writing to inform you of my regular interactions with one of your MN students, Stacy. I conducted online writing consultations with her four times last quarter on her proposal. I have worked with her five times during this quarter on her culminating paper. Today, I found myself giving her the same feedback on the culminating paper as I’d done in March when I first saw it. This was concerning to me, and I wanted to know if I have just really been missing the mark with my feedback and not actually helping this student with her writing process and writing skills. I also wondered if I was overstepping my authority with prompts about fulfilling the expectations of the assignment.

In our first session, Stacy wanted feedback on “clarity, focus, and sentence structure” (her words). I provided feedback on those aspects of her writing. I also shared observations on degree of details, transitions and explicit connections, consistency, and this observation:

I’m not sure if you satisfied the assignment. It’s not clear to me whether this paper is supposed to discuss the courses and your learning in general or supposed to dive much deeper and discuss what you did in the classes, what you learned from those activities, and how those lessons learned relate to the curriculum and MN goals in DETAIL. For instance, I found myself asking, “How?” in many parts of your paper. How did she learn that? What action did she perform and how did it lead to that skill or realization?

And I provided margin comments such as:

How? What knowledge did you acquire? How does that knowledge translate to “skills”?

What is the underlying knowledge? How did you acquire it?

What did you learn, exactly? Where [sic] there certain kinds of analysis that you learned? What analytical practices did you use?

In our second session, Stacy wanted feedback on “grammar.” I provided feedback on subject-verb agreement, singular-plural agreement, verb forms, and sentence structure. In our third session, Stacy wanted feedback on “structure, organization, sentence structure, formatting, and punctuation.” I provided comments on commas and APA headings, and I explained them in terms of conventions and reader expectations. In our fourth session, Stacy wanted feedback on “formatting and citations.” I commented on inconsistencies in those aspects and also on verb forms.

In our fifth session, today, Stacy wanted feedback on “flow”—presumably because she’d added much new content to address your recent comments. My feedback largely centered on interpreting her comments in concrete terms and keeping the focus on her learning experiences, as this excerpt hopefully demonstrates:

It seems to me that you may not have addressed Dr. [Professor]’s comments to the fullest extent. I think she’s asking for explanations and examples of how you evaluate knowledge. This is just another way of asking about your critical thinking skills. Are you someone who takes information at face value or are you someone who thinks when you hear or read something, “Hmm. I don’t know about that. What about this angle or what about that angle?”

Specifically, I think she’s asking in some places about whether these courses prepared you to do scholarship and teaching or actually made you do them in the course. Your wording “prepared to me [sic] achieve” or “prepared me to understand” is a little confusing because it doesn’t give me a straightforward answer about what you learned about in class vs. what you actually performed in class. If you did DO scholarship or teaching (or other kinds of thinking and activities in class), then I think she’s asking you to describe what assignment you did them for, what you personally did for the assignment (your actions), and how those actions demonstrate your critical thinking.

And I provided margin comments such as:

What is the underlying knowledge? Are you saying that the underlying knowledge is how to access a website? Are you saying that the underlying knowledge is a person’s health history? Or is the underlying knowledge something else?

Again, it’s not clear to me what you mean by “underlying knowledge.” Can you be more specific about exactly what knowledge or kinds of knowledge serves as the foundation of this topic and how this course made you evaluate that knowledge?

My tutoring approach honors a student’s authority regarding his or her development and attempts to apply what I know about the value of scaffolded, focused feedback. I’m heartened that Stacy continues to reach out for support and be open to revising her text. I told her in my closing comments today that I know the big-picture stuff isn’t what she wanted to hear at this point, but you and I are telling it to her in order to make her the best writer and this the best culminating paper possible for her right now. Please let me know if you see other ways I can help Stacy and your students.

Professor’s Reply to Tutor’s Email

Hi Amy,

Thanks for the update and information. I could tell from her last draft that she had worked with someone on grammar, sentence structure, etc. as my editing was fairly minimal. But, as you could see from my comments, her responses to the questions were still not hitting the mark. Your comments to her are/were right in line with my own...hopefully, she can see that she is getting the same type of comments from multiple sources. And, no, I just don't have any additional suggestions about ways to help her as much of these she has to come to herself. Let me know if there's any additional information you need.

thanks again for all you do for our students!

Dr. [Professor]

Conclusion

Lastly, I offer as data the note that Stacy left for me upon the conclusion of our last tutoring appointment together. I returned from a meeting to find a handwritten thank-you card on my desk. Stacy’s message here (“I cannot find words to thank you enough for your invaluable help”) is both heartwarming and heartbreaking to me: we had just shared so, so many words. Yet now not one came to her. For all my leading towards precision and description in the culminating paper, perhaps I’d led her to think that her own unworked words weren’t good enough. Or that language isn’t suitable if it isn’t retooled a dozen times. While that may be true for some documents, it’s certainly not true for all, even in graduate school—for graduate school is about scholarship and friendship, originality and collegiality. I wish Stacy and all students could feel comfortable with whatever their own words are when interacting with writing tutors. I never wished and never will that words would disappear on someone as they stop calling themselves “student” and say “professional” instead.

I have words but, as Stacy graduates and I prepare to leave this position, there’s little chance my words will find her. I hope they reach other graduate students, writing tutors, professors, and university decision-makers to inform and encourage.

Epilogue: Tutor’s Imagined Reply to Student

Dear Stacy,

How ironic that the day you came into the Writing Center, I wasn’t present to finally meet you! It’s only fitting, I guess, that we should say goodbye in writing instead of in person.

How can it be goodbye, though, when I have so many questions for you, so many insights still to glean from you? Do you give all your instructors thank-you cards? Did you know, when you first contacted me in the fall, that I was a sort of instructor, not an editor? I tried to explain my role in our early encounters, and we soon settled into a productive dynamic, but I wonder if it would have been helpful to be more explicit at the onset, even at the first mention of the Writing Center by a professor.

I’m often apprehensive when graduate students come to the Writing Center because some professor told them to—in my experience, the referral can make students down on themselves as students or down on their writing as adequate graduate work. You were neither. You were eager to advance the clarity of your document and improve key writing skills. Your eagerness taught me, Stacy, to be open to each student, because it’s not just the professor who wants “better writing” but also the student who—obviously—craves the same. It must feel both disappointing and liberating to be singled out by the professor for work with a writing tutor. Disappointing because it suggests your writing doesn’t meet expectations, but liberating, I’d think, because from it you finally have knowledge of and permission to use help! I bet no professor told you that education is a collaborative pursuit, and that graduate school is too crazy hectic for you to get the most out of it if you’re going it alone. All experts try their hardest, as you did, and use resources and references when they expend themselves. You didn’t see all the times I reached for the APA manual and grammar guides to be able to give you thorough comments! I think this is what it means to make, and be part of, a scholarly community. Wherever you are and wherever I go, we are still in this community together.

Before we became close, through written words, why did you trust me? Was it desperate, “blind” trust? Or did I do something particular to show you my ability to guide you through a high-stakes situation? It was helpful to know that you were listening and that I wasn’t wasting time offering comments to closed ears or a closed mind. Your trust challenged me to refine my role, reinforce my boundaries: I didn’t want to write the paper for you; I didn’t want to command your revisions. So I had to remind myself that you trusted me to help you write the paper—to give personalized advice and lead you towards language that felt right for you.

To do this, I practiced turning statements into questions. Not, “This subject and verb don’t agree,” but “How many people are you talking about? Does it make sense to use the plural form?” Sound familiar? So many questions and comments, I know. Wasn’t it difficult for you to read so many notes from me? Did you read the headnote and margin comments with the same consideration? Doing so takes up your precious time and forces you to process in formal English instead of relax into Spanish. I was giving you more work! But hopefully doing so also gave you new terms to use and a few more quiet moments attending to your paper, your voice. In grammar and in analysis, I wanted us to wonder together, and I wanted you to take the last word. You can contribute to the “scholarly conversation” among your peers when you’ve talked yourself to, and through, a big analytical project that exercises your critique, creativity, and conviction.

As you progress as a nurse with a Master’s degree, I hope you find words to probe your statements as if I were around, or inside your head, commenting on your thoughts. I hope you find words to tell other graduate students like yourself what writing tutors can do for their thinking, writing, self-awareness, and self-esteem and how crucial it is to walk the line between a beginner’s mindset, open to advice, and an emerging expert’s opinion, formed by literature and learning. In the meantime, I will tell tutors about what I did and how I came to advocate more strongly and tutor more mindfully from an eager, trusting graduate-level English-language-learning professional student. Thank you.

Best wishes,

Amy

Notes

1. To preserve the anonymity of the parties involved, the program website is not provided.