Making Failure Meaningful

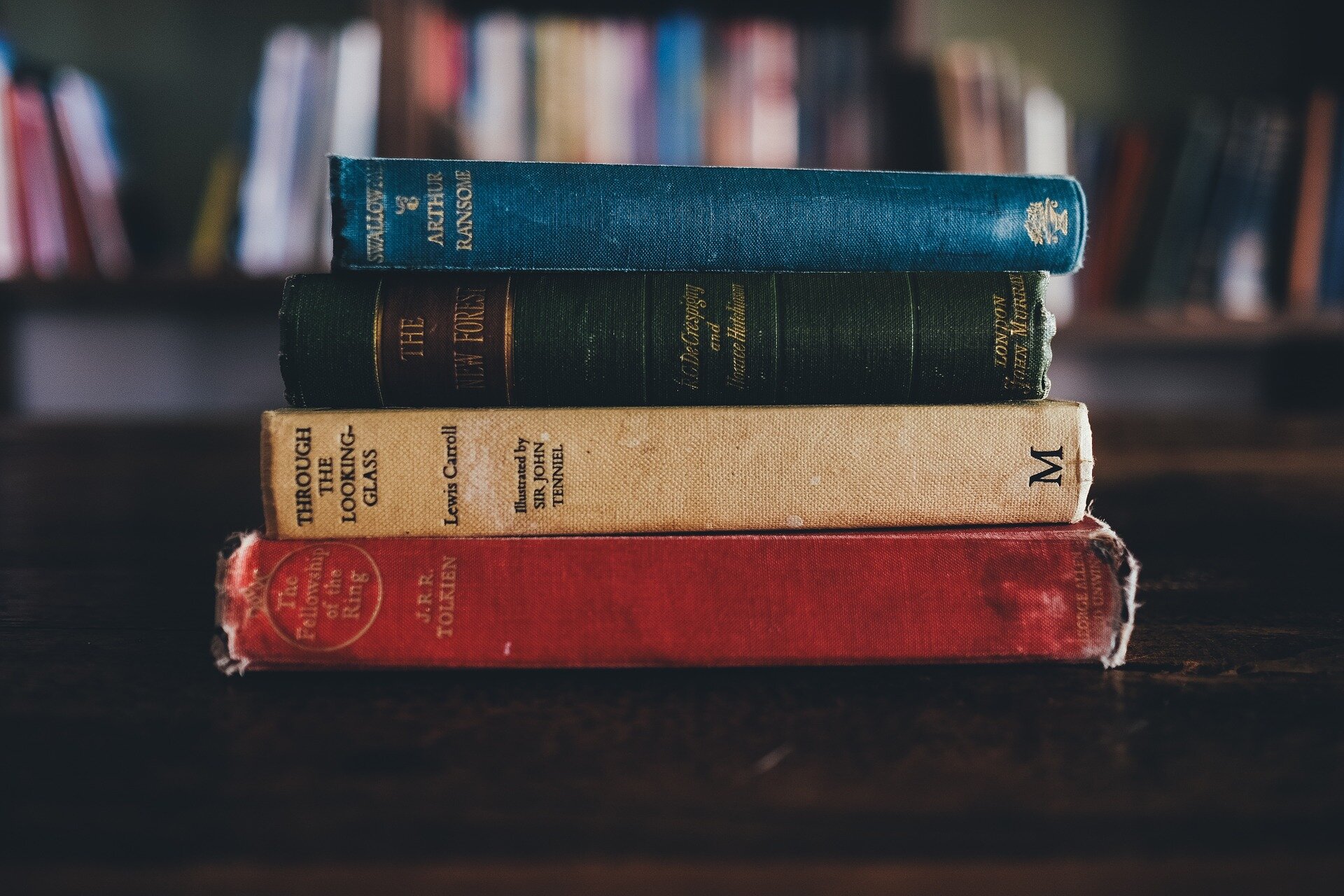

/Image by Annie Spratt from Pixabay

It’s often said that our failures provide the best opportunities for learning in life. When we fail, we’re confronted by a question and a decision. What happened, and what will I do to improve for next time? The way we proceed from there has big ramifications for our successes and failures down the road.

But if our failures are so instructive, then what place does failure have in a sophisticated learning space like a writing center? You don’t often hear academic institutions, or any institutions for that matter, say that they desire or even tolerate failure. And yet failure is inextricably linked to our growth as writers and as people. Therefore, any writing center honestly devoted to student learning must inevitably confront the failures of both clients and consultants. How writing centers do that in the most positive and healthy ways would seem to be a topic of particular interest to writing center scholars and pedagogists.

I’ll provide a personal experience. I once consulted an English-speaking female freshman who was looking for some “touch up” on her paper for an introductory American history class. For much of our initial conversation, she seemed convinced that her paper required nothing more than a superficial look-over for sentence level inaccuracies. But after comparing her writing, which outlined the history of the civil rights movement, to her prompt, which asked for substantive arguments about the effects of certain events on that history, it became apparent that there was a deep, global misunderstanding of the assignment.

I broached the topic delicately, asking her if she recognized that she was missing something crucial in many of her paragraphs. At each turn, she denied that she saw anything wrong. As I pursued the subject, she eventually retreated so far as to say she did not understand what I was asking, and that there was no way for her to fix her problems. It became apparent to me that she was quite unfamiliar with college writing style despite being a top student in her high school years, and that this interaction could possibly determine her comfort level with college writing for years to come. At that moment, I decided to say what I thought would help her more than anything else I could say: I told her she failed.

Of course I didn't use those terms; our non-directive policy forbids us from passing judgement like a professor. But in diplomatic writing consultant language, I explained that she had accomplished objectives she had not been asked to tackle. She simply had written the wrong paper. I could see the immediate consequences of my words on her face, her bleary eyes shedding a tear as she listened on. I knew what I was saying was not what she wanted to hear, but what happened next vindicated my approach.

For the remainder of our session, we took her existing writing and research and weaved an intricate argument into it. As we worked, I could see her disappointment slowly shift to determination. By the time we finished, she was armed with a brand new outline which built upon the accomplishments of her previous draft. As the consultation ended, I could see a new spark of confidence in her, and no trace of the helpless, defeatist mentality from before.

I was proud. Not just of myself, for pushing my comfort zone, but also of her, for responding to failure with a growth mindset and accepting her new challenge. I didn’t have to tell that freshman girl what I did, but I know that she left the writing center better prepared for college writing than when she walked in. What I learned that day is that the writing center can be a place where writers – with the help of an expert – can confront their failures, and grow.

~Barak Bullock